Was the SDFI Sold Too Cheaply?

The sale agreement between the Norwegian state and Statoil was announced by Minister of Petroleum and Energy Olav Akselsen (Labour Party) and Statoil CEO Olav Fjell on May 3, 2001. The deal gave Statoil a 50 percent boost in petroleum reserves.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nedrebø, R. (2001, 4. mai). Fjell-stø tro på milliardkjøp. Stavanger Aftenblad.The stated purpose was to strengthen the company’s reserve base ahead of its planned stock exchange listing later that year. Hydro also acquired 5 percent of the SDFI portfolio.

A favorable deal for Statoil

Minister Akselsen maintained that genuine negotiations had taken place, and that the shares were sold at market value — even though the state was effectively on both sides of the table.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nedrebø, R. (2001, 4. mai). Fjell-stø tro på milliardkjøp. Stavanger Aftenblad.

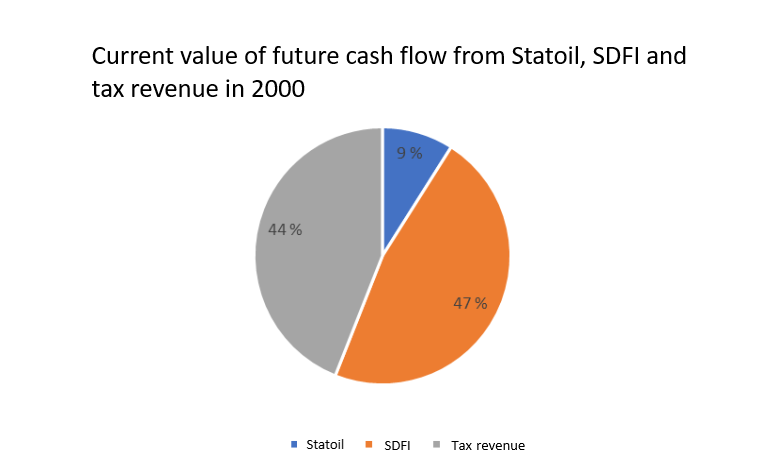

It’s hard to say how accurate that claim really was. In December 2000, the ministry estimated the net present value of future SDFI cash flows at around NOK 230 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Olje- og energidepartementet. (2000). St.prp. nr. 36 (2000–2001): Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE. Tilråding fra Olje- og energidepartementet av 15. desember 2000, godkjent i statsråd samme dag. Regjeringen. S. 16 https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stprp-nr-36-2000-2001-/id204183/?ch=1 The gross value of the portfolio was significantly higher (NOK 660 billion), but roughly 65 percent of that would have returned to the state via taxes and fees if sold. The NOK 230 billion figure therefore reflects what private buyers could expect to gain — after taxes. Statoil paid NOK 38.6 billion for 15 percent of the portfolio, which matches up fairly well with the estimated value per percentage point.

The real question is whether the NOK 230 billion estimate was too low — or whether the shares Statoil purchased represented more than 15 percent of the portfolio. If either were true, then the state sold the assets too cheaply.

Since SDFI holdings aren’t regularly traded, it’s difficult to determine their true market value. There’s no way to know what might have happened if the shares had been auctioned openly to a broad pool of buyers.

What is clear is that officials in 2000 significantly underestimated the value of Norway’s offshore resources. Their estimate of the state’s total expected cash flow from petroleum at that time was NOK 1,400 billion. Had they seen into the future and accounted for actual revenues between 2001 and 2023, they would have valued the shelf several times higher.

In fact, between 2001 and 2023, the state received petroleum-related revenues that — when adjusted for risk with a 7 percent discount rate and converted to 2001 prices — amounted to NOK 2,732 billion.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The annual cash flow (sourced from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate) was weighted using a discount rate of 7 percent per year. For example, revenue the state received in 2003 was multiplied by 0.93 × 0.93 × 0.93. The figures for each year were then added together and adjusted for inflation to reflect 2001 values, using Statistics Norway’s inflation calculator. This approach was used because the Petroleum Directorate reports cash flow in inflation-adjusted prices. In other words, even in a hypothetical scenario where the shelf yielded nothing after 2023, the 2001 valuation would still have been only half of what it should have been.

Cash flow after the selloff

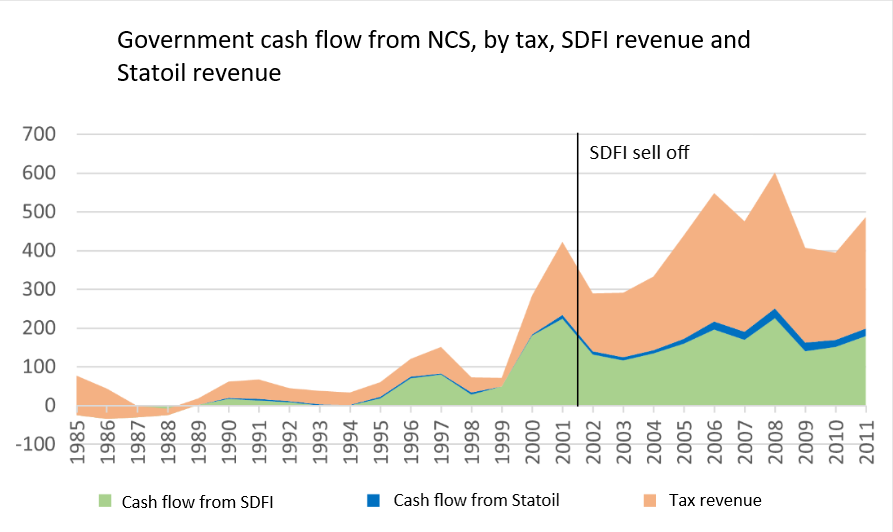

Between 2001 and 2002, the state’s revenues from the SDFI and petroleum taxes dropped by 30 percent — a NOK 133 billion decline.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The figures are sourced from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate’s fact pages and are presented in 2023 prices It took until 2005 for cash flow to return to 2001 levels — and by then, oil prices had doubled.

To the extent that this drop was caused by the sale of SDFI shares, two conclusions can be drawn — one fairly confidently, the other with more caution:

First, it’s highly likely the state lost money by selling part of the SDFI in 2001. The ministry had estimated the value of the portfolio at NOK 660 billion, with 65 percent of that (NOK 430 billion) expected to return to the state through taxes and fees regardless. The estimate was based on assumptions about future oil prices and production levels that turned out to be too low.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The production curve from Proposition No. 36 (2000–2001): Ownership in Statoil and Future Management of the SDFI (p. 18) has been compared with historical data from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate covering the same period: https://www.sodir.no/en/facts/production/ With better foresight, the estimated market value would have been higher.

There is greater uncertainty around whether Statoil paid below market price. The post-sale decline in state revenues suggests they may have — the drop in cash flow in 2002 alone was double the amount Statoil paid.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate reports cash flow figures in 2023 prices. To enable comparison, the NOK 38.6 billion that Statoil paid for 15 percent of the SDFI has been adjusted using Statistics Norway’s inflation calculator, resulting in NOK 64.8 billion. Oil prices and Norwegian production levels were relatively stable at the time. But again, because there was no open auction, the true market value of the shares remains unknown.

In other words: it’s reasonable to say the shares were sold too cheaply. How much of that was due to misjudged future prices and production — and how much to deliberate underpricing for Statoil — is unclear.

There’s also a structural reason why the state may lose out in any SDFI sale, even if the sale is priced at full market value: high return requirements in the petroleum industry. Oil companies demand very high returns on capital due to risk, capital constraints, and long investment lead times. Private companies tend to use higher discount rates than the state, meaning they’re less willing to pay full price for license shares — especially if those shares haven’t yet entered production.

This supports the argument that the state, over time, stands to benefit from holding large ownership stakes on the shelf.

Even bigger ambitions

While the 2001 divestment may not have been a win for the state, it could have gone much further. Harald Norvik, Statoil CEO from 1988 to 1999, had pushed for the entire SDFI portfolio to be transferred to Statoil free of charge. A McKinsey team was hired to develop the case. But in a meeting between Norvik and then-Minister of Petroleum and Energy Finn Kristensen, it quickly became clear that the proposal was a non-starter.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Based on an email exchange with Kyrre Nese. Over the course of 41 years, Nese has held positions including platform manager and chief petroleum engineer.

Petoro after the sale

Since the divestment, Petoro has adhered to a guiding principle: it does not sell license shares for cash. This complicates any potential transactions, because the company must receive something in return that is nearly identical in value. As a result, Petoro has rarely traded license shares during its lifetime.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Conversation (23 October 2024) between the author and Kjell Morisbak Lund (Director of License Follow-up and Technology at Petoro) and Ørjan Heradstveit (Head of Communications at Petoro).

In May 2024, Petoro carried out its largest license transaction since the 2001 sale. The goal was to keep the exchange as neutral as possible — that is, without significantly altering the oil-to-gas ratio, cash flow distribution over time, or the overall value of the portfolio.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Petoro. (2024, 14. mai). Bytte av deltakerandeler mellom SDØE ved Petoro AS og Equinor ASA. Petoro. https://www.petoro.no/nyheter/bytte-av-deltakerandeler-mellom-sd%C3%B8e-ved-petoro-as-og-equinor-asa-14-05-2024-11-00

Petoro’s license swaps resemble a kind of barter system, where — with government approval — the company can rearrange ownership shares, but only in ways that leave the portfolio’s total value unchanged.