The Tow from Stord to the Field

Even for world-weary industry professionals, this was something special. Never

before had gravity been challenged on this scale in this way.

A total of 130,000 horsepower was available to tow the structure to its final

destination. Never before (or since) have people moved such a heavy object.

One and a half million tonnes of concrete and steel were to be moved from Stord

to the field, a distance of 154 nautical miles.

The platform extended 210 metres down into the depths. On the way out to sea,

the shallowest point was 215 metres deep, leaving just a few metres of

clearance. For stability, Statoil [now Equinor] wanted the platform to extend

as deep as possible. But the company also had to ensure adequate safety

margins. Running aground was not an option; that would have gone into the

history books in a way nobody wanted.

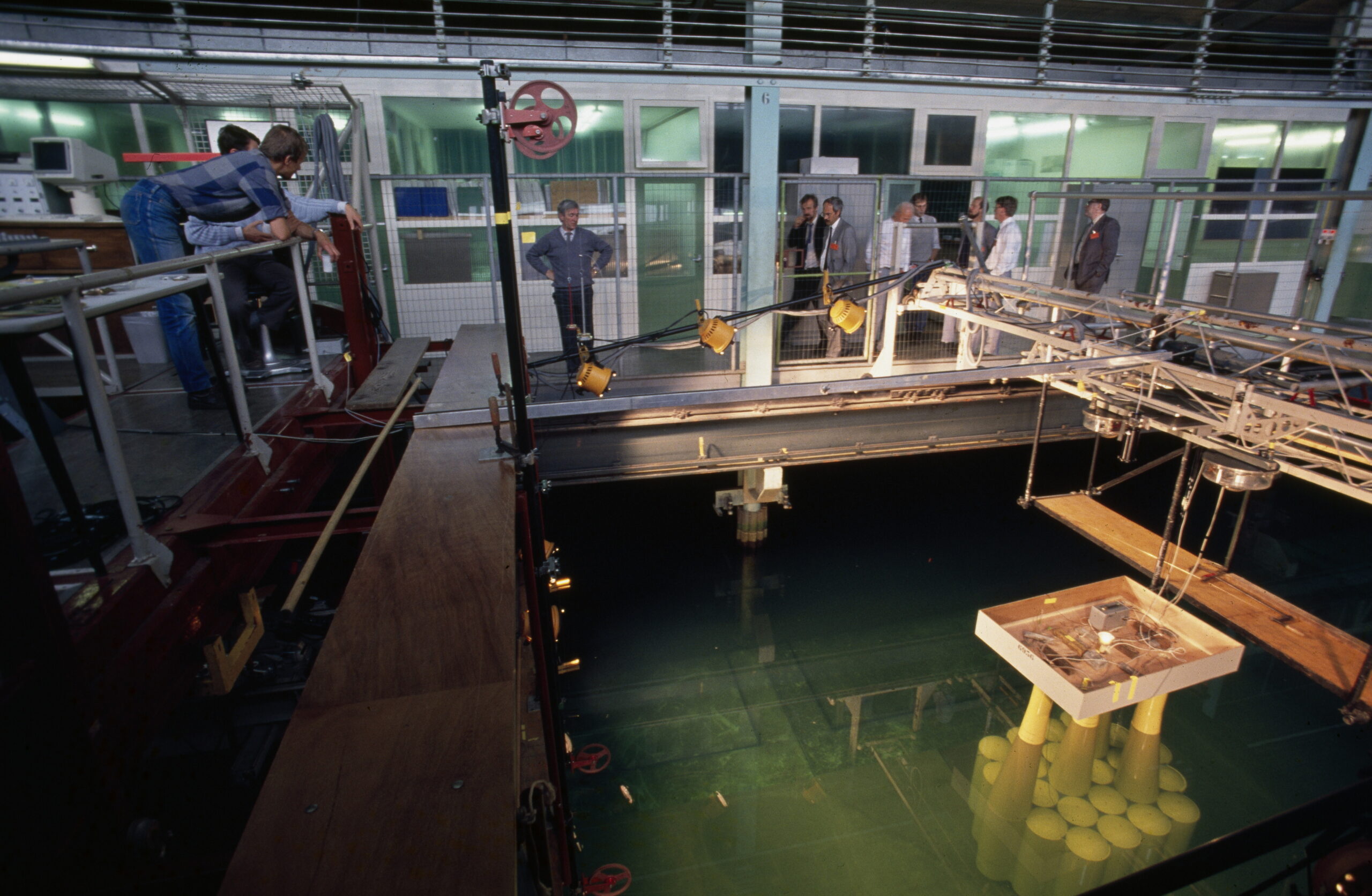

Extensive testing had therefore been carried out beforehand to see how towing

speed could affect the platform. Among other things, it was important to map

how much the base of the platform moved sideways at different speeds. The

reason was that “if the base of the platform does not stay level but tilts

from side to side, greater clearance to the seabed is required. The platform

then has to be higher in the water and the topsides weight reduced.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hansen, Thorvald Buch et al. (1990). “Gullfaks – Glimpses from the History of a Fully Norwegian Oil Field.” Stavanger: Statoil, p. 111.

But the challenges were not only below the surface. The platform’s height above

the sea surface made it difficult to pass through Langenuen, a narrow sound

between Stord and Tysnesøy. Here the power line span had to be raised higher so

that the minimum clearance above the sea surface was about 200 metres.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hansen, Thorvald Buch et al. (1990). “Gullfaks – Glimpses from the History of a Fully Norwegian Oil Field.” Stavanger: Statoil, p. 129.

Gullfaks C emerged safely from the Norwegian fjord landscape and now had only

open sea between it and the field. The towing speed was 1.7 knots. The tugs

were directed from a control centre on the platform.

The tow arrived at the field a day ahead of schedule, but the final setting

down on location was postponed because of bad weather. The wind could not be

stronger than 10–15 knots, and even though each day of waiting cost millions,

the tow master, Tormod Reppe, was crystal clear: “So much value is at stake

here that taking any chances is out of the question.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Jupskås, Stein Halvor (6 May 1989). “A 16-Billion-Kroner Colossus.” In: Stavanger Aftenblad, p. 6. And he had his reasons:

several pipelines lay close to the planned setting-down point.

On 8 May the lowering of the platform could begin. Its own weight pushed it

down into the seabed at a rate of a quarter to half a metre per hour. On

10 May, no storm could budge the platform any longer – the skirts of the base

section then extended 18 metres into the seabed. The deviation in the

platform’s position was minimal (three metres south and seven metres east). The

Operations Division in Bergen now formally took over the platform.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For the tow-out and submersion, see:

– Hansen, Thorvald Buch et al. (1990). “Gullfaks – Glimpses from the

History of a Fully Norwegian Oil Field.” Stavanger: Statoil,

pp. 126–128.

– Jupskås, Stein Halvor (6 May 1989). “A 16-Billion-Kroner Colossus.”

In: Stavanger Aftenblad, p. 6.

– Status (1989), No. 9. “The Gullfaks C control centre in operation.”

(p. 16, Journalist: Egil Risnes)

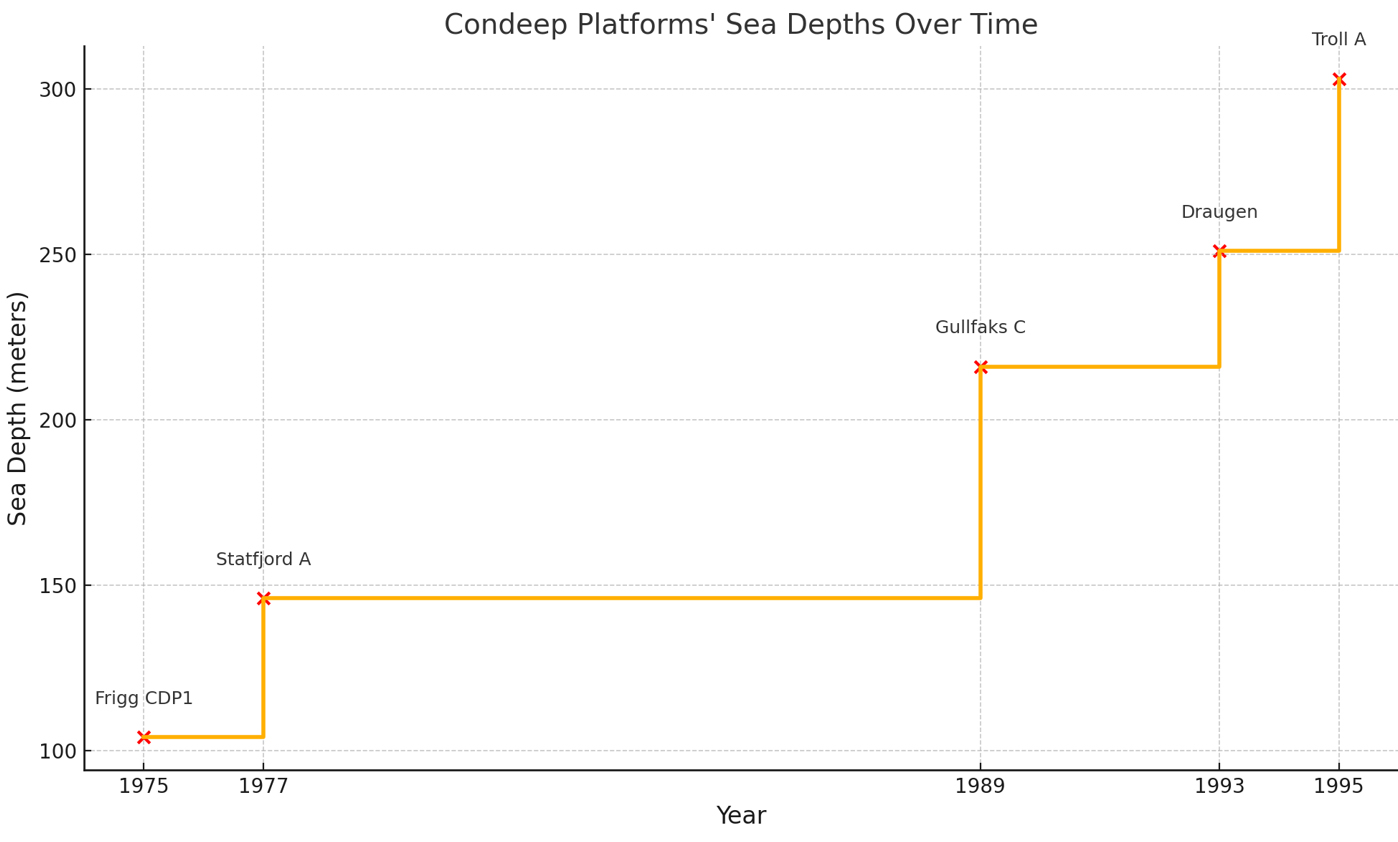

A big leap in water depth

Gullfaks C was the first Condeep to be designed for installation in water

depths of more than 200 metres. That was significantly deeper water than for

the earlier Condeep platforms. Gullfaks A was installed in 135 metres of

water, Gullfaks B in 141 metres. Statfjord A, B and C all stood in 145 metres

of water.

Installed in 216 metres of water, Gullfaks C beat its predecessors’ record by

71 metres. This jump would turn out to be the largest in Condeep history. A

few years later, Draugen was installed in water 35 metres deeper (251 metres),

while Troll A, with 303 metres of water beneath it, surpassed its predecessor

by 52 metres.

It is also worth noting that the 262-metre concrete substructure was actually

more than 100 metres taller than the substructure on Gullfaks A.

——————————–

The figure below shows which Condeep on the Norwegian continental shelf has, at any given time, been installed in the greatest water depth. The distance

between Statfjord A and Gullfaks C represents the largest single leap, but the

record lasted only four years and was broken by Draugen in 1993. Troll A is

today the Condeep installed in the greatest depth. Note that Condeeps tethered

to the seabed with tension legs, such as Snorre A and Heidrun, are not

included.