The Story of Extinguished Flames

The year is 1985. On a spring night, a man walks the decks of a platform far out on the British continental shelf. A keen birder, he pauses – as he often does – to watch the migration clearly visible in the glare of the powerful flare flame. He shudders as several birds fly straight into the flame, get singed, and fall into the sea.

The man is Thormod Hope. Perhaps this is the first time he asks himself whether there might be a way to snuff out this “giant bird barbecue.”

Just under ten years later – in 1994 – he managed it.

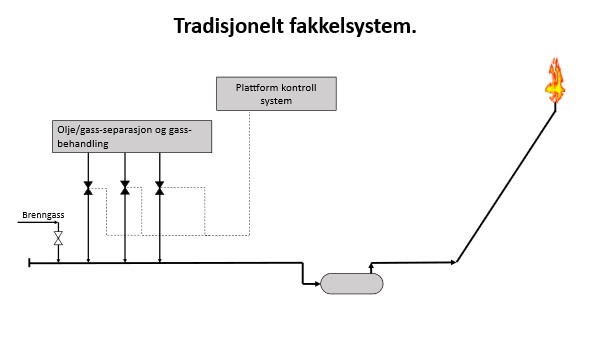

The traditional flare system

On the Norwegian shelf, routine flaring is only allowed when necessary for safety reasons.

The flare system is part of the safety system and should only be used during start-up, shutdown, and blowdown. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate [now Norwegian Offshore Directorate] specifies that flaring solely to produce oil has been prohibited since production began on the Norwegian shelf.[REMOVE]Fotnote:Sokkeldirektoratet, “Utslipp og miljø,” in Ressursrapport funn og felt 2019, https://www.sodir.no/aktuelt/publikasjoner/rapporter/ressursrapporter/ressursrapport-2019/utslipp-og-miljo/, accessed March 24, 2024.

In other words, it has never been legal in Norway to burn off the gas and produce only the oil, as is still done in several other countries.

Traditionally, gas has been less valuable than oil and somewhat harder to transport over long distances. On some fields abroad, gas is still burned rather than produced.

Despite the ban on burning gas unnecessarily, the flare was—on safety grounds—always lit. Gas was continually purged through the flare system to prevent oxygen being drawn back in through the flare boom. Without a purge, you could get flashback: ignition inside the flare itself.[REMOVE]Fotnote:All statements from Thormod Hope are drawn from an interview conducted with Julia Stangeland and Kristen T. Hetland, January 11, 2024.

From time to time the flare also received unwanted gas from one or more of the many valves on the platform. That gas could come from problems with the gas turbines that generate electricity offshore, or from other process upsets.

Put simply: surplus gas can build dangerous pressure. That pressure must be relieved, and the only safe way to do so was to route the gas up the flare boom and burn it.

In other words, the flame could not be extinguished until someone found another way to relieve dangerous pressure. In addition, there had to be a system or method to re-light the flare in truly critical situations.

Was it really such a good idea to turn off the flare? Were there any arguments that could trump safety?

Reduced costs and higher revenues

On 8 April 1991, Thormod Hope presented the project “Reducing gas to the flare system.” He requested NOK 800,000 to pursue work that would, with luck, result in extinguished flares.[REMOVE]Fotnote:Tron M. Landsnes, Utviklingen av det alternative fakkelsystemet: en aktørnettverk-studie av teknologisk utvikling (master’s thesis, Sosiologisk institutt, Universitetet i Bergen, Spring 1999), 37–38.

Hope says the introduction of the CO2 tax was a prerequisite for proposing work to shut down continuous flaring. Another economic argument was that gas could be sold rather than burned. At the April 1991 meeting, Hope used the Gullfaks C platform as an example. He explained that the platform consumed roughly 9.5 million Sm³ of gas each year just to keep the flare system running. In addition, about 11 million Sm³ leaked into the flare system annually. For Statoil, the value of this gas is estimated at roughly NOK 12 million per year. The CO2 tax would add a cost of about the same.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Landsnes, Utviklingen av det alternative fakkelsystemet, 37–38.

Hope also pointed to less quantifiable arguments: climate considerations, promoted by the Norwegian state and public opinion, and the large gas volumes on Gullfaks.

Climate concerns may have counted for less than the economics, but even with arguments about lower costs and higher earnings, Hope did not get the management backing he needed from Statoil.

Tron M. Landsmark, who wrote a graduate thesis on what he calls the alternative flare system, notes that the official, bureaucratic reason was that the project did not align with the 1991 goals. Hope was urged to apply again the next year. The other, unofficial reason was that nobody believed the emissions could be reduced to any significant degree.[REMOVE]Fotnote:Landsnes, Utviklingen av det alternative fakkelsystemet, 47.

Landsmark adds that there was a general risk aversion in petroleum operations. Nobody wanted to challenge API RP 14C.

“Obsession”

API RP 14C, developed by the American Petroleum Institute, is an international safety standard for the oil and gas industry.

After the 1991 rejection, Hope reflected. The standard was not in its first edition, which meant it had been challenged and revised before. If he and his colleagues could propose a system at least as safe, they might gain acceptance from the Petroleum Safety Authority [now Norwegian Ocean Industry Authority].

Hope teamed up with a former classmate, Magne Bjørkhaug of Statoil, who held a PhD in gas explosions—an ideal partner for a flare project.

As 1991 went on, the effort became a private project for Hope and Bjørkhaug – or an “obsession,” as Hope puts it. – I thought, to hell with the flare. I just want to figure it out, Hope said.

Waiting for another chance to apply in 1992, the two aligned with Hope’s former workplace, Gullfaks C. In September 1991 they traveled to the platform to discuss and investigate seven points they had laid out in advance. In March 1992 they planned a similar trip to the same platform.

Before that second visit, fog kept them waiting at the heliport. The conversation turned, naturally, to the flare.

In Bjørn Vidar Lerøen’s book, 34/10 Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet, the proposal Hope and Bjørkhaug sketched while sitting at the heliport is dubbed “the napkin proposal.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjørn Vidar Lerøen, 34/10: olje på norsk: en historie om dristighet (Stavanger: Statoil, 2006), 115–16.

The sketch may look, in the book, like something conjured from thin air on an idle day. It is important to stress that the proposal was the result of long-running work on the topic, and of ruling out several other options.

So what did the solution involve?

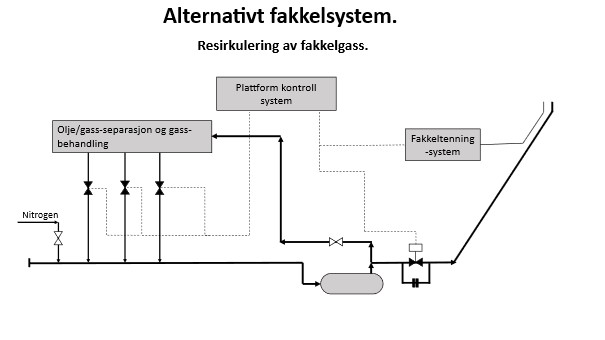

The alternative flare system

Three elements were crucial to designing an alternative flare system that remained safe: 1) Gas had to be prevented from reaching the flare under normal conditions. 2) Gas still had to be able to reach the flare in critical situations. 3) When it did, the gas had to be ignitable.

In addition, the purge stream that had previously circulated to the flare had to be replaced to prevent flashback. That was solved by using nitrogen instead of natural gas.

Hope and Bjørkhaug’s “napkin proposal” relied on a valve called the Mockwell valve, placed in parallel with a rupture disc. Both would stop small amounts of natural gas while, in a critical situation, lifting out of the way rather than forming plugs.

Where gas had previously been sent up the flare, it would now be blocked by these two devices and recirculated back into the process. Instead of being burned, the gas could be sold.

Both Hope and Bjørkhaug believed this setup was at least as safe as the traditional flare system—if not safer. The people on Gullfaks C agreed. The system also complied with API RP 14C requirements for two safety barriers operating independently of one another.

Challenges one and two were now solved. The next step was to ensure the flare would ignite if uncontrollable volumes of gas forced their way past the barriers and up the flare.

The flare ignition system

Both Thormod Hope and Magne Bjørkhaug were confident a solution could be found. They believed an automatic version of the “air-rifle principle” ought to be possible—in other words, a way of lighting the flare with the equivalent of a starter pistol.

Hope says Bjørkhaug engaged the company Techno Consult to design a flare ignition system. After some back and forth, the Raufoss ammunisjonsfabrikk agreed to manufacture a projectile for the system. Techno Consult then brought in the Bodø firm Restech to work on it.

Hope maintains that “the work done was incredibly poor,” pointing to things like wrong dimensions and materials, bullets jamming, and the impact plates falling down.

He says this ignition system ran only briefly before being replaced by another design developed by Sandsli driftstenester. The projectile was modified and, instead of firing toward a plate, it was shot into a barrel capped with a mesh. The barrel and mesh kept the projectile contained while ensuring the sparks could escape.

The flare system was patented, but not the ignition system. That patent has now expired.

Time to tell the story of the flares that were extinguished—and those that still burn.

The system in operation

With an almost-complete system to show off, it was easy to gain Statoil’s management’s ear. Kværner in Stavanger carried out the front-end work. Sandsli drift was tasked with the detailed design.

On 16 November 1994, the first flare was shut down—on Gullfaks A. Just one month later, the flare on Gullfaks C was extinguished as well.

Asked why the flare on Gullfaks B was not also shut down, Hope cites internal disputes and rivalry between platforms. In his view, that is also why the flares never went dark on the Statfjord platforms.

Landsnes gives a different explanation for why the Gullfaks B flare kept burning: the platform did not have a low-pressure compressor.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Landsnes, Utviklingen av det alternative fakkelsystemet, 83 (in the footnotes).

Even if not all legacy flares on the Norwegian shelf are dark today, Hope believes this approach has become standard when new platforms are built.

World Bank figures support that. At the most recent “flare count” (2022), only 31 flares on the Norwegian shelf had a continuous flame.[REMOVE]Fotnote:World Bank, “Global Flaring and Venting Regulations,” https://flaringventingregulations.worldbank.org/norway, accessed May 2, 2024.

In 2023 the Norwegian shelf emitted 180 million Sm³ of natural gas,[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Dette inkluderer mellom anna CO₂-utslepp og metanutslepp,” https://www.iea.org/energy-system/fossil-fuels/gas-flaring, accessed May 2, 2024. including both continuous flaring and flaring linked to critical events and restarts after shutdowns.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Information on CO₂ emissions on the Norwegian continental shelf is drawn from an email from Halvard Hedland (Sokkeldirektoratet) to Julia Stangeland, April 5, 2024.

Norway’s annual flaring is about one per mille of global flaring, which in 2023 totaled 140 billion Sm³ of natural gas.[REMOVE]Fotnote:“Gas Flaring – Energy System – IEA,” https://www.iea.org/energy-system/fossil-fuels/gas-flaring, accessed May 2, 2024.

The high global volume is partly because not every country has rules as strict as Norway’s on unnecessary flaring—so the gas is burned while only the oil is produced.

If this gas were produced instead, it would still ultimately be burned and CO2 released. The difference would be that energy was extracted first—perhaps even reducing annual gas production. As things stand, a great deal of energy quite literally goes up in smoke.

A memory of an old flame

In 2004, ten years after the alternative flare system went into service, Hope quotes a newspaper article with the apt title “In memory of an old flame.” He reads the ending: “10 years ago, to see a flare on a platform was viewed as a symbol of good and clean production. Nowadays good and clean production is represented by a flare less flare boom.”

Hope himself maintains that what he and Magne Bjørkhaug came up with in the early 1990s was not some radical invention.

– In hindsight it’s not anything particularly clever – you just picked from existing ideas, copied things and put them together. It wasn’t a big deal, really, but the problem had to mature. You have to define the problem and look at solutions, he said.

Landsnes thinks that kind of reflection is typical among innovators: what looks like pioneering from the outside can, from the inside, feel like the right puzzle pieces coming together by chance.

How groundbreaking the alternative flare system truly was is hard for a layperson to judge. Perhaps the most important breakthrough was that Hope refused to accept that a flare had to burn.

In January 2024, Thormod Hope was interviewed about the ignition system. For over two hours he spoke about the system he and Magne Bjørkhaug deserve much of the credit for. He clearly has good memories of the old flame, and especially warm feelings about the time when the flame went out.