The Concrete Metropolis

1987. How did the village experience this transformation?

For a relatively small community (and the surrounding area), handling some

2,000 workers at once offered both opportunities and challenges. What if a

major accident happened? To what extent would locals find work and would

businesses thrive? What did people make of the boom, and how much did

Norwegian Contractors’ activity actually contribute in kroner and øre?

Emergency preparedness

Emergency preparedness was tested on 3 June 1987 in a large-scale drill

simulating an explosion on a barge moored alongside Gullfaks C, with three

fatalities and fourteen injured. It was the largest disaster exercise in

northern Rogaland since 1980.

The drill involved the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre, the hospital in Haugesund, the police, and physicians in Vindafjord. One lesson was that routines for keeping a continuous head count on the platform could be improved. The same applied to information flow to the public, the press, and relatives. In addition, it took too long

before the “injured” reached shore.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Vestvik, Einar and Carlsson, Ronny S. 1987. NC testet ny beredskapsplan med katastrofeøvelse: «Eksplosjon på Gullfaks C, minst tre drept og 14 skadd». In: Haugesunds Avis 04.06.1987, pp. 1 and 22.

Local recruitment and ripple effects

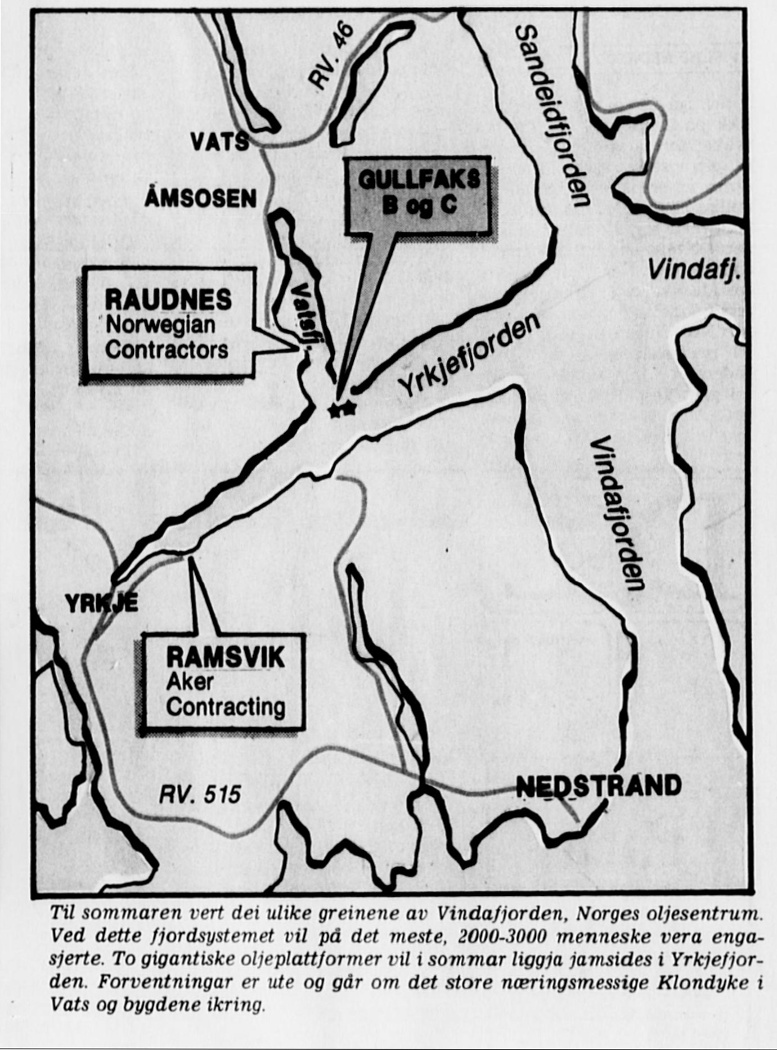

The Gullfaks B substructure arrived in Vats on 29 April 1987 to be mated

with the topsides. The project team counted about 130 people, many of whom

were quartered on Gullfaks B. Some 400–500 from Rosenberg Verft were housed

in barracks at Raudnes. Their task was to install the connections between

the concrete base and the topsides on Gullfaks B. The platform departed for

the field on 31 July.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Is, brus og ny plattform. (no author) In: Status, nr. 5 29. april 1987, p. 6.

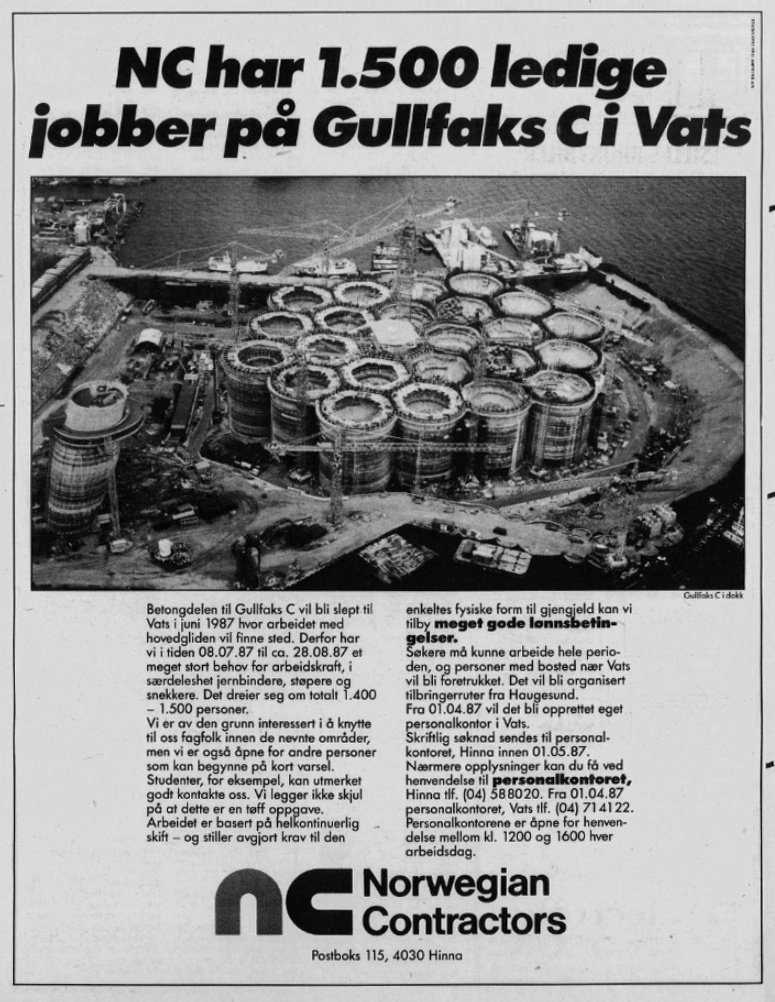

The base section for Gullfaks C arrived in Vats at the end of May. The main

slipforming phase—the vertical casting of the cell walls atop the base—

was scheduled to start on 8 July. This meant casting work, not just mating

topsides and substructure, and would require a very large workforce—far

more than earlier Vats projects. Recruiting enough people therefore became

a major job in itself. NC pursued an explicit recruitment strategy focused

on Vats and the surrounding area. The logic was simple: for every worker

able to go home after their shift, the need for a bed in the Raudnes camp

by Vatsfjorden shrank.

The big projects in Vats naturally drew substantial attention, not only

locally but regionally as well. Haugesunds Avis reported that Gullfaks C

would produce “considerably greater ripple effects for local residents and

businesses than any of the previous platform operations in Vats. In July

and August alone, around 2,000 temporary employees will be fully engaged in

casting work. A large share of these will be people from northern

Rogaland.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amble, Bjarte 1987. Gullfaks C skaper lokal optimisme: Ankommer Vats tirsdag kveld. In: Haugesunds Avis 25.05.1987, p. 2.

Svein Ove Vik, head of the Vats and Skjold Business Council,

believed the Gullfaks C project would mean “stronger competition for local

labour but also greater purchasing power among residents.” His bottom line

was that this was positive for the local economy, especially since NC, over

the years, had become increasingly open to local suppliers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amble, Bjarte 1987. Næringslivet i Vindafjord ligger frampå: Gullfaks B og C skaper aktivitet. In: Haugesunds Avis 27.05.1987, p. 1.

Among those hired from the area for Gullfaks C, there were two main groups.

One consisted of experienced rebar fixers and concrete workers; the other

was inexperienced youths who, over time, could step into those roles. The

inexperienced handled tasks such as pushing wheelbarrows of concrete.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Heggebø, Thorleif 1988. «Raske penger på gliden: Prester, bønder og

studenter i kø». In: Status (Statoil) 1988, Nr. 5, pp. 8–9. https://www.nb.no/items/95b68bcc9236fe101ad4543f69b14e13?page=7&searchText=%22Gullfaks%20C%22

Pay for the unskilled was good—about NOK 110 per hour—but NC’s

communications manager, Vidar Vorraa, stressed that people would earn it:

he said workers would “feel it in their arms” after the seven weeks, as the

job involved pushing heavy concrete in wheelbarrows and lifting rebar.[REMOVE]Fotnote: 200 på «sommerjobb» i Vats: -Nesten som i militæret (u. forf.) 1987.

In: Haugesunds Avis 08.07.1987, p. 2.

The soon-to-be student Knut Molnes Jr. from Etne said his first encounter

with industrial Vats felt strange: everything was new, and he admitted he

didn’t feel particularly confident those first hours. He started on the

night shift, and fortunately that first night was not too fast-paced, which

made for a softer introduction. Those first wheelbarrows full of cement

were wobbly, he said, but he later got into the groove—vibrating concrete

in addition to hauling it.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Eidhammer, Anne Ma 1987. På Raunes er det plass for alle. In: Grannar 16.07.1987, p. 5.

What did older locals think about taking jobs in the concrete works?

Per Gunnar Heggebø, a mason from Ølen (a short drive northeast of Vats), said

the pay was undeniably tempting. He also thought it would be fun, for a short while, to try a place that gathered people from all over the country. He spent his summer holiday on the concrete project. Johannes Nygård from Bjoa (north of Ølensvåg) had previously run, among other things, a transport firm, but profitability had been limited. He said it was exciting to try something new that he had heard much about but never done before— and, as he put it, the pay did not exactly detract from the appeal.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Eidhammer, Anne-Ma 1987. Gull(faks)feber. Spaning og pengar lokkar. In: Grannar 16.07.1987, p. 5.

The commuter and the room-hunter

Some employees commuted daily (especially early on) across Boknafjorden,

which could be demanding for anyone not a committed early bird.

One worker, Else Marie, admitted she did not load her wheelbarrow too full on day one. She hoped to get a bunk in Vats soon, because, for the standard day shift start, she had to set the alarm for four in the morning when commuting from

Stavanger—too early, in her view.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bikuben i Vats. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 21.07.1987.

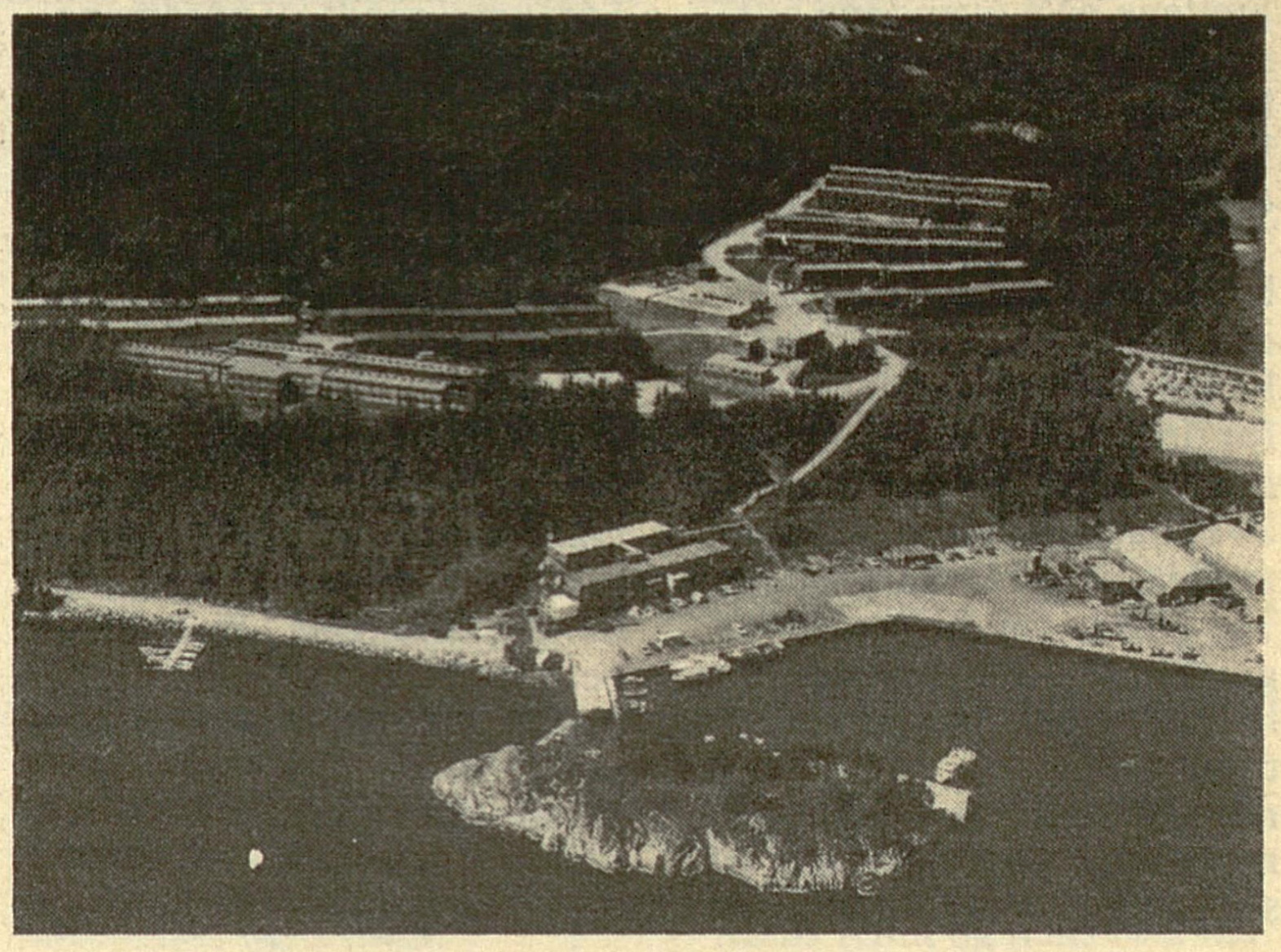

Local opinion and NC’s contributions

Vindafjord’s mayor, Trygve Mikal Viga, summed it up by saying the

municipality had, over time, grown used to having platforms “visit” the

fjord. But he added they had never before had two platforms being worked on

at once, nor such a prolonged operation as the Gullfaks C concrete build.

They had been very curious how the summer influx would play out. So far, he

had not noted any material downsides.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Reynolds, Inger 1987, Bygda som fikk storinnrykk. In: Status nr. 5,

19.08.1987, p. 17.

The mayor pointed to increased road traffic through the village, especially

to and from Raudnes, but at the same time the municipality had gained a

four-kilometre road to the Raudnes yard and upgrades to other roads.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See Ny veg til Raudnes opna (no author) In: Haugesunds Avis 02.07.1987, p. 17, and Reynolds, Inger 1987, Bygda som fikk storinnrykk. In: Status nr. 5, 19.08.1987, p. 17.

Norwegian Contractors spent a two-digit million-kroner sum on roadbuilding

linked to the Raudnes industrial area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas et al. 1987. Historisk sommer: Klondyke i Vats. In:

Stavanger Aftenblad 27.03.1987, p. 13. See also: Ny veg til Raudnes opna

(no author) In: Haugesunds Avis 02.07.1987, p. 17.

Tysvær municipality also got a new road to the base at Ramsvik (south of Yrkjefjorden), which Aker Contracting had built.

There was no doubt the community reaped several benefits from NC’s

presence. In 1983, Norwegian Contractors granted five million kroner toward

what—together with municipal funds and volunteer efforts—became the

Vindafjordhallen complex, with a culture venue and swimming pool. The

building was completed in 1993 at a total cost of NOK 20 million.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas 1994. Fryktar framtid utan betongkjemper. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 04.05.1994, p. 29. See also Førde, Thomas 1993. Prektig kulturhus i Vats: Oljedrypp og dugnad. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 17.04.1993, p. 38.

In connection with the big influx, NC also built a new sports hall at

Raudnes. This rescued Vindafjord’s local volleyball push, which could not

meet approved playing conditions (ceilings too low) in the local gyms for

third-division play. Otherwise the team would likely have withdrawn. It was

no surprise, then, that Haugesunds Avis ran the headline “Oil saved

Vindafjord volleyball.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ringodd, Hans Inge 1987. Olja berget Vindafjord-volleyballen. In:

Haugesunds Avis 09.01.1988, p. 10.

In short, Vindafjord municipality did get to share a bit of the oil wealth,

though still far from what neighbouring Tysvær had long enjoyed as host to

Kårstø.

Some of Mayor Viga’s neighbours expressed admiration for what was going on,

while also noting the aesthetic limits of platforms: impressive feats and

technology, yes—but it was just as well the platforms would stand out in

the North Sea. They were fine to look at, but not so fine that locals

wanted them there forever.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Reynolds, Inger 1987, Bygda som fikk storinnrykk. In: Status nr. 5,

19. august 1987, p. 17.

At the end of July 1987, Gullfaks B was towed out of Vats, and at New

Year’s 1988/89 Gullfaks C also left the area, bound for Stord to be mated

with its topsides. The enormous workload was over.

What next, Vats?

Read more in: The Quiet After the Boom? and From Backwater to «Norway’s Oil Capital»