Parliament greenlights Gullfaks, Statpipe, and Kårstø

During the consideration of Parliamentary Proposition 102 (1980-81), which focused on bringing gas from the Statfjord and Heimdal fields to shore, Parliament had to address several issues with significant economic implications.

The key matters included deciding how and where to bring Statfjord gas to shore, the development of Gullfaks, upgrading the oil refinery at Mongstad, setting the takeover date for Statfjord, and clarifying the companies’ roles in the Troll field. [REMOVE]

Footnote: Lerøen, B.V. (2006). 34/10 Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet. Statoil, s. 74

In the lead-up to and during the parliamentary discussions, several lines of conflict emerged, related to the geographical ripple effects of petroleum activities, Statoil’s role on the continental shelf, the pace of resource extraction, and the solutions for bringing gas ashore. Below is a brief overview of the key players, institutions, and political parties, and their positions leading up to and during the debate.

Statoil and Mobil strongly advocated for the swift development of a pipeline solution to bring Statfjord gas to Kårstø. Statoil likely saw the issue as a golden opportunity to launch the prestigious project in Block 34/10 (Gullfaks). If Gullfaks entered production, it would increase the volume of gas that could be transported through the pipeline, thereby making the gas pipeline more profitable.

who years earlier, in 1979, Statoil had applied for an exemption from the requirement to bring oil ashore in Norway, opting instead to continue loading via buoys and exporting the oil abroad. The application was approved, but at that point, it was still too early to determine a solution for the gas.

The lack of a permanent gas solution would eventually pose major problems for the Statfjord group. Restrictions on flaring (burning off gas) led to large amounts of gas being reinjected into the Statfjord reservoir. While this could continue for several years, in the long run, the reinjection could negatively affect oil production. The licensees estimated that by 1985, the volume of associated gas (gas dissolved in oil at high pressure but separating when the pressure drops) would be so large that the platform’s facilities wouldn’t be able to process it all. Without an export solution for the gas, oil production would have to be scaled back. The clock was ticking.

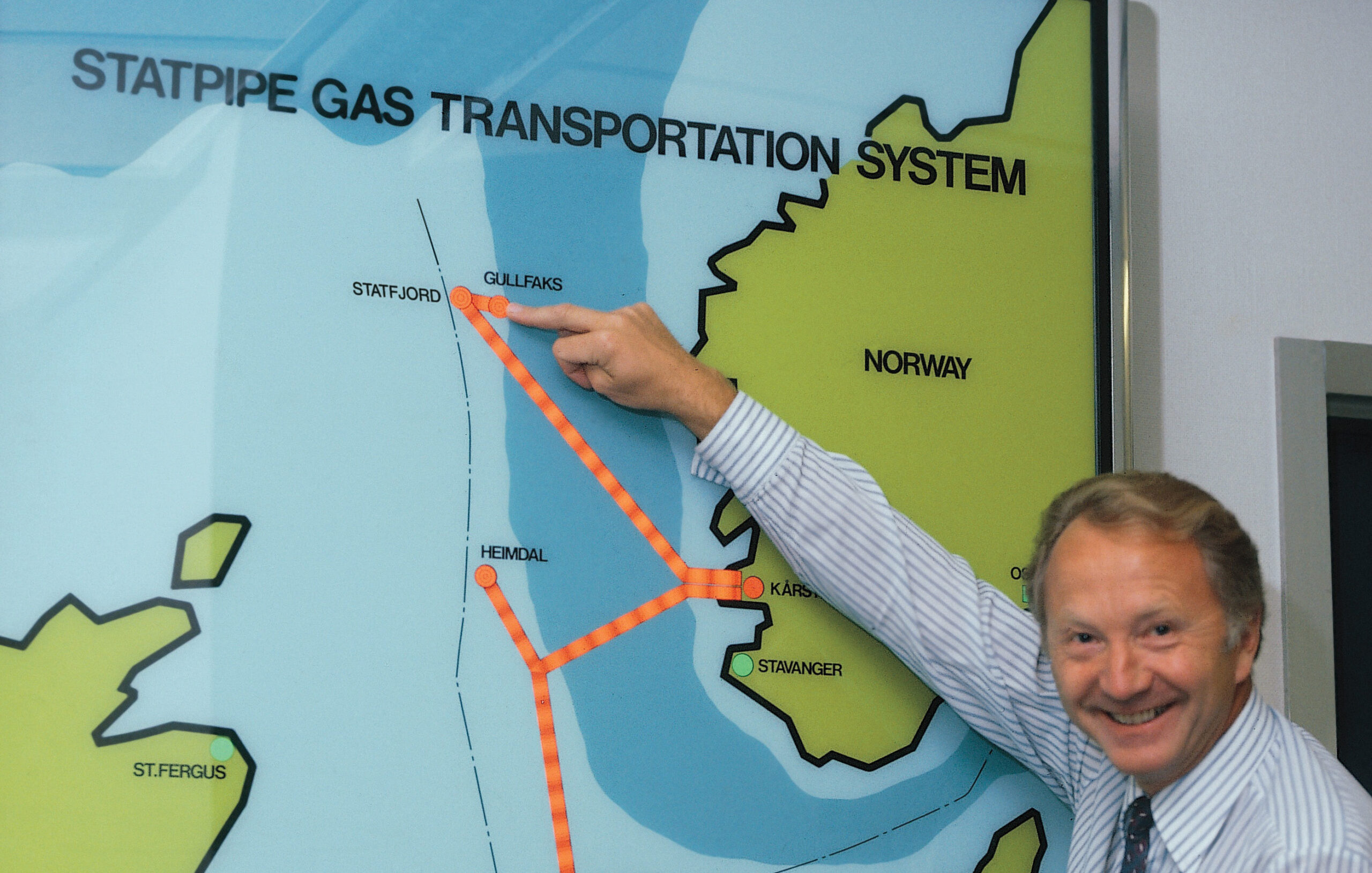

The Statfjord group decided they wanted to send the gas to Kårstø and submitted their application on December 22, 1980. Their plan was for the gas pipeline to pass through Gullfaks and Heimdal (which was scheduled to start production in 1986). Gas not used in Norway would then be sent to Ekofisk, where capacity was opening up due to declining production, and onward to Emden, Germany.

According to the Statfjord group’s plan, the pipeline would have the capacity to transport a total of 4 million cubic meters (MSm³) of gas per day from Statfjord, 3 MSm³ per day from Heimdal, 1 MSm³ per day from Gullfaks, and 7 MSm³ per day from other fields. Statfjord, Heimdal, and Gullfaks would have priority access. This solution ensured a dual benefit: Statfjord gas would reach the market while the pipeline also justified the development of new fields.

[REMOVE]Footnote: St.prp. nr. 102 (1980-81) – Ilandføring av gass fra Statfjordfeltet https://www.stortinget.no/no/saker-og-publikasjoner/stortingsforhandlinger/lesevisning/?p=1980-81&paid=2&wid=b&psid=divl163&pgid=b_0017

Hydro, which was not a co-owner of Statfjord, strongly advocated for an alternative solution where the gas from Statfjord would be sent to Mongstad in Hordaland. The gas not used in Norway would then be routed via the Frigg field (where Hydro was the majority owner, though not the operator) to Ekofisk, and from there to Emden, Germany.

The Hordaland representatives in Parliament and local politicians from the region had two major issues on the table, both of significant regional importance: bringing gas ashore at Mongstad and the development of Gullfaks.

The representatives from Hordaland supported Hydro’s alternative plan, with Mongstad as the receiving terminal. This could create more jobs in the region, both directly through the development and operation of Mongstad, and indirectly through the ripple effects of the activity and the potential for industrial development based on the gas brought ashore. However, the majority of the parliamentary industry committee had endorsed the Statfjord group’s Kårstø solution, and the Hordaland representatives were likely aware that the chances of getting Mongstad approved were slim.

This made it all the more important to secure the realization of the other major project with a clear Hordaland profile: the rapid development of Gullfaks. Statoil’s administrative center had already been established in Bergen, and the Gullfaks block could play a crucial role in Hordaland’s aspirations to become a key oil-producing county.

[REMOVE]Footnote: Lerøen, B.V. (2006). 34/10 Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet. Statoil, s. 75

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) was more cautious about whether it was a good idea to start developing Gullfaks. Gullfaks was primarily an oil field, and its gas reserves played a minor role in the socio-economic profitability of the gas pipeline.

The NPD argued that new large oil fields could exceed the production cap of 90 million tons of oil equivalents and recommended focusing on smaller fields in the southern North Sea instead.

The political parties were divided along several lines. The debate over Parliamentary Proposition 102 (1980-81) touched on core partisan conflicts, including Statoil’s role on the continental shelf. Gullfaks was a large, but complex field, making it an ambitious project for the then nine-year-old Statoil to tackle. The Labour Party and the Conservative Party were on opposite sides regarding how quickly and how much Statoil should be allowed to grow.

The proposition also raised the issue of production pace. Several parties in Parliament (the Centre Party, Socialist Left Party, Liberal Party, and partly the Christian Democratic Party) advocated for a lower production cap and were skeptical about launching new large projects. On the other hand, the Labour Party, Conservative Party, and Progress Party supported a high production cap and were less concerned about the size of Gullfaks in light of that limit.

Lastly, the question of ownership of the gas infrastructure was debated. The Socialist Left Party pushed for 100% state ownership of the gas pipeline system. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy considered it sufficient that Statoil’s corporate bylaws and requirements for permits to establish and operate the transportation system set certain guidelines.

The outcome

The parliamentary debate concluded with a compromise between the Labour Party and the Conservative Party, resulting in an agreement that the ministry should prioritize the development and gas landing of the Delta East field in Block 34/10 on the Norwegian continental shelf. The government was also requested to present a plan for the phased development of the block to Parliament.[REMOVE]Footnote: Lerøen, B.V. (2006). 34/10 Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet. Statoil, s. 79

The decision allowed work to begin while also giving politicians the flexibility to slow down or halt the phased development if circumstances warranted it.

Additionally, Parliament approved the construction of the Statpipe system for bringing gas ashore. Statoil was made the majority owner (with a 60 percent stake) and was given operational responsibility for the developments.

As expected, the choice of location for bringing gas ashore favored Rogaland. In Parliament, 94 representatives voted in favor of the terminal at Kårstø, while 54 preferred Mongstad.

Early Development Plans for GullfaksThe name became Gullfaks