New Tax Regime

Less than a year before Gullfaks came on stream, the oil price dropped to about one-third of its previous level. The government responded with sweeping changes to the petroleum tax regime.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ot. Prp. Nr. 3 (1986 – 1987) Om lov om endring i lov av 13. Juni 1975 om skattlegging av undersjøiske petroleumsforekomster m.v

Several of these changes had consequences for Gullfaks and, in sum, probably reduced the project’s net profitability.

This article primarily focuses on the tax changes themselves and the rationale behind them, rather than their specific impact on the Gullfaks project.

It covers three key changes:

- Foreign oil companies were no longer required to cover the state’s exploration costs

- Companies were allowed to begin depreciation for the special tax in the same year as the investment, instead of waiting until production began

- The production tax was abolished

- The uplift allowance was replaced with a production-based deduction

1. Ending Foreign Companies’ Obligation to Cover State Exploration Costs

As of 1 January 1987, foreign companies were no longer required to cover the state’s (Statoil’s) exploration costs—a practice known as cost sharing. Norwegian companies had already been exempt from this requirement since 1979, much to Statoil’s protest.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Osmundsen. T. Gjøkungen – Skal Statoil styre Norge? Dreyer forlag 1981 s. 57The exemption was now extended to foreign companies as well. By removing the arrangement, the government likely aimed to stimulate more exploration activity on the shelf.

The cost sharing arrangement worked roughly as follows: When exploration licences were awarded to private companies, Statoil received an option to join the licence within one year of a potential commerciality declaration. During the exploration phase, private companies bore all costs. If the licence did not result in a commercially viable discovery, Statoil could choose not to exercise its option. For a foreign company, this meant paying for exploration in an area with no commercial find. If exploration was successful, however, Statoil had one year from the commerciality declaration to decide whether to join. If it did, Statoil would assume its share of exploration costs and subsequently receive a corresponding share of the revenues once production started. The arrangement functioned somewhat like the state having the right to buy into your lottery ticket if it won, while leaving you with the entire cost if it didn’t.

Why did cost sharing reduce exploration activity?

Consider a simplified numerical example. A company is evaluating whether to explore an area where it believes there’s a 50% chance of a commercial discovery. The exploration cost is NOK 20 million. A successful discovery would yield an expected post-tax profit of NOK 50 million.

So the company faces:

- A 50% chance of losing NOK 20 million (exploration cost)

- A 50% chance of earning NOK 30 million (profit minus exploration cost)

Based on these figures, the company would choose to explore, since 30 is more than 20.

Now imagine Statoil has an option to acquire 50% of the licence if a viable find is made. If no find is made, Statoil does not join, and the private company bears the full NOK 20 million loss. But if a profitable discovery is made worth NOK 50 million, Statoil would likely use its option. In that case, Statoil assumes half the exploration cost (NOK 10 million) and receives half the profit (NOK 25 million). So the private company is left with:

- A 50% chance of losing NOK 20 million

- A 50% chance of earning NOK 15 million (25 million revenue – 10 million costs)

Now the company would not explore, because 15 is less than 20. It must bear the full downside risk but only receives half the upside.

The project’s possible outcomes and the companies’ expected returns prior to exploration are summarised below. “Expected return” refers to the two possible outcomes (discovery and no discovery), weighted by their respective probabilities:

- Without cost sharing: 50% × NOK 30 million + 50% × (–NOK 20 million) = NOK 5 million

- With cost sharing: 50% × NOK 15 million + 50% × (–NOK 20 million) = –NOK 2.5 million

2. Depreciation for the Special Tax from Year One

Before we look at the 1987 changes to depreciation rules for the special tax, it is helpful to give a brief overview of what tax depreciation is. Norway taxes corporate profits through the corporate income tax. If you invest NOK 100 and earn NOK 150, your profit is NOK 50, and this is the amount subject to tax. The way this works is that the state takes a fixed percentage of both your revenues and costs. Using corporate tax (22% on profits) as an example:

- The state collects 22% of the NOK 150 you earned (NOK 33)

- But it also covers 22% of your NOK 100 in costs (NOK 22)

So you pay NOK 33 in tax on income but receive NOK 22 in tax relief on your costs. The result is a net tax payment of NOK 11, which is 22% of the NOK 50 profit.

“Depreciation” refers to the portion of your costs that can be deducted from taxable income—in other words, the part of the investment the state will reimburse you for. The main question is when and how this happens. For corporate tax, which all companies (including oil companies) pay, depreciation begins when the company starts earning revenue and is spread out over six years from the start of production.

The 1987 change affected depreciation for the special petroleum tax, which oil companies pay in addition to corporate tax. Introduced in 1975, the special tax was initially set at 24%, on top of corporate tax. Together, these levies brought the total effective tax rate on petroleum profits to around 78%. As corporate tax rates declined over subsequent decades, the special tax rate was increased to keep the total tax burden around 78%.

The special tax functions similarly to corporate tax in that it taxes profits—taxing both revenue and providing deductions for costs. But it differs in how these deductions (depreciation) are handled. The 1987 reform allowed companies to start depreciating investment costs for the special tax from the year the investment was made, rather than waiting until production began. In other words, oil companies no longer had to wait until a field came on stream to receive the state’s share of the costs.

Why did the change stimulate activity on the shelf?

Depreciation ensures that companies get back a fixed percentage of their investment costs. But the timing of the refund has a major impact on investment decisions. That’s because a krone today is worth more than a krone tomorrow. If companies can get reimbursed for “the state’s share of costs” immediately, they can reinvest the money elsewhere—either in new offshore projects or even a bank account that earns interest.

By allowing companies to start depreciating from day one, the state’s role in the tax system becomes more like that of a regular licence co-owner—sharing in both costs and revenues. The change made the special tax more investment-neutral. An interesting side effect was that there was less incentive to rush production start from one calendar year to the next. The new rules may have contributed to a more even distribution of field start-up dates throughout the year.

3. The Production Tax Is Abolished

n addition, the production tax was removed for fields that had received development approval in 1986 or later. The production tax was a levy on gross sales rather than profits.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The production tax on the Norwegian continental shelf has often been referred to—somewhat misleadingly—as “royalties,” a term that normally refers to payments for the use of intellectual property. A royalty is a fee paid to rights holders such as authors, composers, or inventors for the commercial use of their work or patents. This kind of tax can have some undesirable effects compared to today’s regime, in which companies pay tax on profits.

The petroleum surtax (special tax) is close to investment-neutral: a project that is profitable before tax should still be profitable after tax. Investing NOK 1 and getting NOK 2 back yields the same return as investing 50 øre and getting NOK 1.

The production tax, however, works differently. It reduces profitability without offering any cost deduction to offset the burden. It thereby makes oil production less attractive. This can lead to lower recovery rates or cause companies to forgo developing fields that would otherwise be economically viable.

Why does the production tax discourage investment?

Under the production tax, a certain percentage of sales revenue went directly to the state. To illustrate how this affects profitability and investment incentives, consider the tax regime in effect until 1972.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Engen. O.A. Hanisch. T. J Oljen: Et skattekammer for skattemyndighetene. Norsk oljemuseum Årbok 1991

This period is useful as an example because the regime was simpler. From 1972, the production tax became progressive (higher rates for larger fields), which mitigated some effects but complicates the example.

Let’s look at the pre-1972 regime, where the production tax was a flat 10% on gross revenues, regardless of field size or profitability. In addition to the production tax, companies paid a 49% profit tax.

Example field: NOK 100 million in costs and NOK 150 million in revenue

Suppose developing a field costs NOK 100 million and generates NOK 150 million in revenue. That means a profit of NOK 50 million.

With the pre-1972 tax regime:

- A 10% production tax on NOK 150 million = NOK 15 million

- Remaining profit: NOK 35 million

- 49% tax on that = NOK 17.15 million

- Final net profit for the company = NOK 17.5 million

The state captures 65% of total profits. But this field is still profitable enough to proceed with development, even with high taxes. But what about less profitable fields?

What happens with less profitable fields?

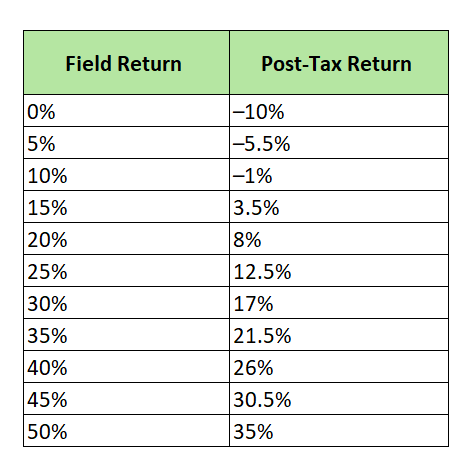

The table below shows post-tax returns for fields with different profit margins. “Field return” is the pre-tax return on investment. For example, if a field costs NOK 100 million and yields NOK 150 million in revenue, the return is 50%. If revenue equals cost, the return is 0%.

A private company is unlikely to invest just to break even. There are two main reasons for this:

- Capital has alternative uses. It could be invested elsewhere, possibly abroad, for higher returns. Companies demand a return at least equal to what they could earn elsewhere.

- Oil and gas investments are risky. Oil prices are volatile, and there are often long delays before revenues start flowing. Companies need higher returns to compensate for these risks.

In 2018, oil companies’ required return on investment was estimated at 13–14%.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: NOU 2018: 17 – regjeringen.no kapittel 8.4.2

It was likely even higher in the 1980s, due to high interest rates. High rates make capital more expensive, and investors demand higher returns, especially for long-horizon projects.

Assuming a required return of 13%, a project would need a field return of over 25% to justify investment. Under the pre-1972 system, all fields yielding less than that would likely remain undeveloped—even if they were technically profitable.

4. From Uplift Allowance to Production-Based Deduction

The final tax measure replaced the uplift allowance with a production-based deduction. Under the pre-1987 uplift system, a portion of oil companies’ profits was exempt from the special tax. The size of this exempt portion depended on how much the company had invested. The uplift was set at 6.6% of the capital cost of operating assets.

The problem with this scheme was that it weakened companies’ incentives to control costs. The higher their costs, the larger their tax exemption. This was especially problematic at a time when low oil prices made cost discipline more important than ever. That is why the government proposed replacing the uplift allowance with a production-based deduction.

The new scheme, like the uplift allowance, exempted part of company profits from the special tax. But now the size of the exemption was based on revenue, not costs. All fields approved for development after 1 January 1986 were allowed to deduct 15% of gross revenues from the special tax base. In other words, 15% of income was shielded from the special tax, regardless of how high the company’s costs had been.

In Broader Terms – The State Assumes Risk in Downturns

The tax reforms following the 1985–86 oil price crash are an interesting example of how the Norwegian state has used policy changes in the petroleum sector to act countercyclically, boosting activity during downturns when companies are hesitant to invest. The rationale lies partly in the different appetites for risk between oil companies and the state. The state is large, diversified, and essentially acts as its own insurer.

This means the state is more tolerant of risk and thus applies a lower required rate of return to its investments than the private market. As noted, oil companies’ return requirements in 2018 were estimated at 13–14%. That is significantly higher than the return the state expects from its investments (7%). In times of great uncertainty over future oil prices, the gap between private and public return requirements likely increases. This creates a case for shifting some of the investment risk from companies to the state—just as was done in 1987, and again during the COVID-induced price crash of 2020.