Gullfaks C: Slipforming and Mechanical Outfitting

Because of the height of Gullfaks C’s concrete substructure, neither the main

slip nor the shaft slip could be carried out in the relatively shallow Gandsfjorden. Yrkjesfjorden and Vats in the northern part of the county then stood out as the best place to do both.

Main slipforming

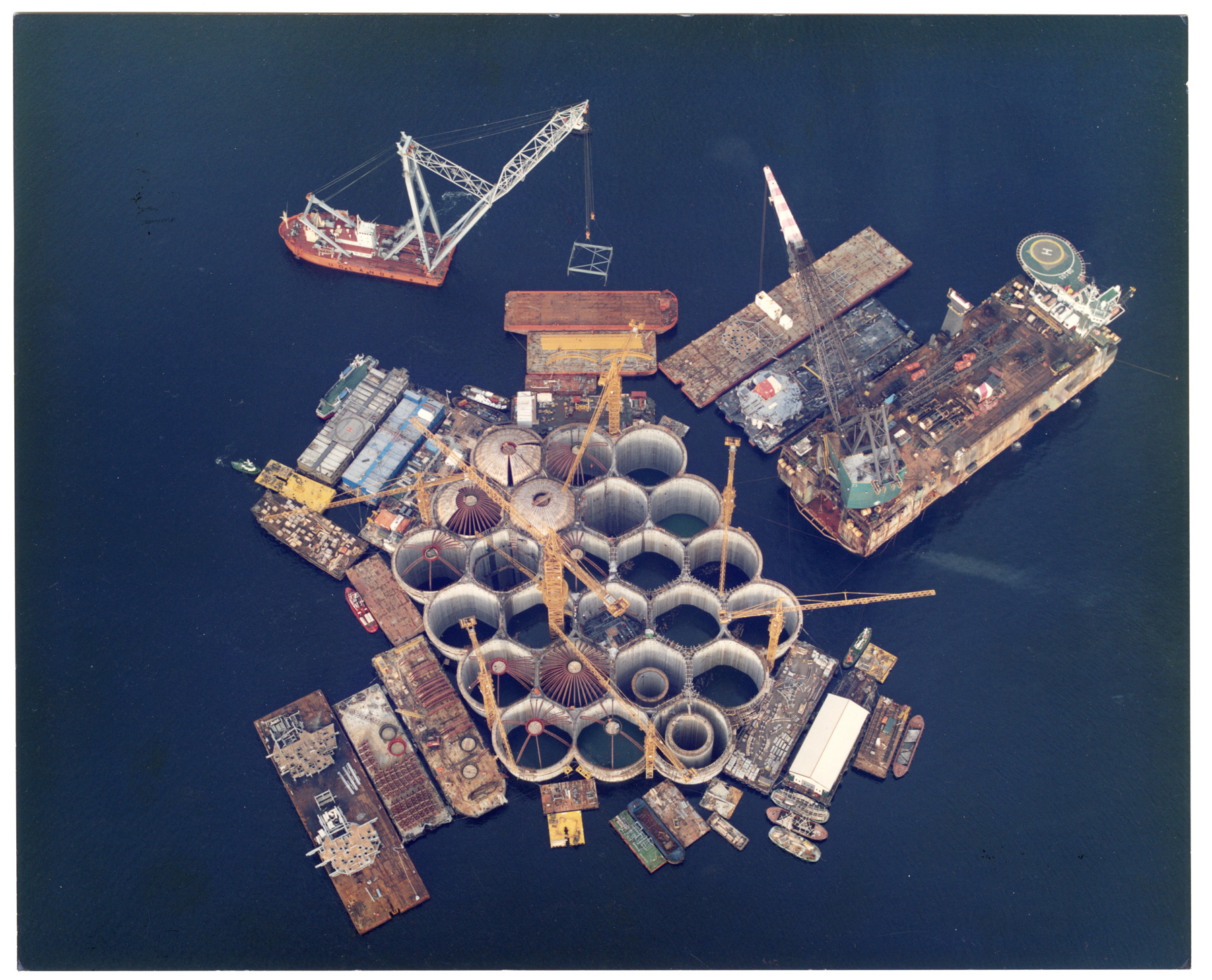

In the summer of 1987, preparations were complete for the main slip—that is,

the (vertical) slipforming of the concrete cells from the base section—the skirts and the bottoms of the cells—to the top of the cell walls. Slipforming means the formwork around the cylindrical cells is jacked upwards in step with the concrete being placed, setting and curing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For more on slipforming, see: Sandberg, Finn Harald: “Squaring the Circle.” https://draugen.industriminne.no/nb/2018/07/02/sirkelens-kvadratur/

Round the clock for seven intense weeks, 2,000 people—1,200 of them emporary hires—made the 24 cells grow by 56 metres. This took 25,000 tonnes of reinforcement steel and 115,000 tonnes of concrete.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind (1993). “På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973–1993.” Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, p. 49. Many a student gained useful hands‑on outdoor work experience in the open air, a world away from studying under reading‑room lamps the rest of the year. After the main slip was finished, the cell roofs (top slabs) were cast.

Shaft slipforming

In February 1988, the project organisation faced several challenges: The task

was to slipform four shafts as extensions of four of the 24 cells already cast.

Each shaft was to be 165 metres tall (by comparison, Oslo City Hall is “only”

66 metres high).

First, shafts that tall had never before been built on a Condeep.

Second, three of the four shafts were to have a three‑degree inclination (to compensate for the larger base and cell section while keeping a deck area roughly similar to Gullfaks A). Slipforming at an angle posed a major challenge for both people and equipment. Here Norwegian Contractors drew on experience from building Skråtårnet in Jåttåvågen.[REMOVE]Fotnote: For information on the Inclined Tower, see Sandberg, Finn Harald:

“The Leaning Tower of Stavanger.”

https://draugen.industriminne.no/nb/2018/05/14/det-skjeve-tarn-i-stavanger/

Third, the client supplemented the traditional practice of moving concrete to

the forms manually by wheelbarrow: Much of the concrete was now pumped into the forms through pipes cast into the shaft walls.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See also Steen, Øyvind (2002). “Den frie tanke – om kreativ frihet og en ledende norsk ingeniør.” Lillestrøm: Byggenæringens forlag, p. 116; and

Steen, Øyvind (1993). “På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973–1993.”

Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, p. 49. One reason NC had long stuck with manual handling was the constant risk of the feed pipes clogging. The shafts were 30 metres in diameter at the bottom, and only 14 metres at the narrowest. Wall thickness varied from 1.8 metres down to 65 centimetres.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Heggebø, Thorleif (1988). “Shaft slipforming for 50 days. The world’s

largest platform rises in Vats.” Status (Statoil) 1988, No. 5, p. 8.

There was no shortage of people keen to join the hectic weeks of this unusual shaft slip. About 800 people applied for the 400 temporary positions as steel fixers and concrete workers. Two‑thirds of those hired were experienced concrete builders, many with a long commute; the rest were largely young, inexperienced workers from the local area. The aim was to train the latter to move into skilled roles on later Condeep projects. Each day shift paid NOK 1,000; a night shift NOK 1,170.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norges Bank’s inflation calculator shows that 1,000 kroner in 1988 is

equivalent to 2,361 kroner in 2023.

https://www.norges-bank.no/tema/Statistikk/Priskalkulator/ Over the 50 days the shaft slipforming lasted, that quickly added up. The Personnel Manager for hourly employees at NC, Kjell Ludvigsen, noted that most trades were represented among the applicants, including missionaries, priests, farmers and school students. In addition came NC’s 600 permanent employees, most of whom lived in the Stavanger region.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Heggebø, Thorleif (1988). “Quick money on the slipform: Priests, farmers, and students lining up.” Status (Statoil) 1988, No. 5, pp. 8–9.

https://www.nb.no/items/95b68bcc9236fe101ad4543f69b14e13?page=7&searchText=%22Gullfaks%20C%22

All told, about 1,000 people were employed at Vats—roughly half the workforce on the main slip. In total, 8,200 tonnes of reinforcement steel and 40,000 m³ of concrete were used, around a third of what the main slipforming consumed. On average, the slip advanced three to four metres per day.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind (1993). “På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973–1993.” Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, p. 49.

Mechanical outfitting

In January 1986, the NOK 800 million contract for shaft outfitting was awarded

to Aker Contracting. The company nonetheless lost significant money on the job

—around a quarter of a billion kroner. The main reason was a severe underestimation of the labour hours required to complete the work.

“We underestimated both the scope and the complexity of the job. On the

engineering side we used 100,000 hours more than planned. The physical work

together with installation in the shaft ran 300,000 hours over. In addition, we

have an overrun in total hours of 400–500,000 hours,” said director Per H.

Houge.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ueland, Margunn (15 September 1988). “Aker loses 250 million on the Gullfaks C shafts. ‘We seriously underestimated the scope and the

complexity.’” In: Stavanger Aftenblad, 15 September 1988, p. 11.

The work included, among other things, external risers, conductor pipes for drilling and stair towers with elevators. A good share of the equipment was manufactured outside Norway—in the United Kingdom, Germany, Finland, Italy and the Netherlands.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hansen, Thorvald Buch et al. (1990). “Gullfaks – Glimpses from the

History of a Fully Norwegian Oil Field.” Stavanger: Statoil, p. 108.