Hywind Tampen: Profitability, Production, and Climate Impact

The cost of Hywind Tampen was estimated at 4.8 billion NOK during the construction phase and 830 million NOK during the operational phase, which is expected to last 20 years. Of this, the state would cover the majority. The license received 2.3 billion NOK in support from Enova and half a billion NOK from the NOx fund. Of the remaining costs, the state assumed 78 percent, as the project is considered an investment under the Petroleum Tax Act.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Blomgren, A., Guttormsen, A. G., & Misund, B. (2023, 3. september). Den sjenerøse oljeskattepakken sikret aktivitet i leverandørnæringen. Dagens Næringsliv. https://www.dn.no/innlegg/olje-og-gass/skatt/klima/den-sjenerose-oljeskattepakken-sikret-aktivitet-i-leverandornaringen/2-1-1509064

Hywind Tampen was thus classified as an oil and gas project.

Economically Unviable

Despite nearly 2.9 billion NOK in subsidies, the licenses expected the project to incur higher costs than revenues. The project’s net present value (NPV)—the value of all future costs and revenues, discounted to their worth today—was negative 331 million NOK in 2019 prices: minus 124 million for Snorre and minus 207 million for Gullfaks.

This makes Hywind Tampen historic in the sense that the changes in the Plan for Development and Operation (PDO) for Gullfaks and Snorre are the first to be approved despite having a negative expected profitability.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Blomgren, A., Guttormsen, A. G., Misund, B., & Julide Ceren, J. A. (2024, 19. mars). Resource rent taxation and indirect subsidization of investment projects on the Norwegian Continental Shelf. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4764629

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate assessed the project as economically unviable for society, meaning that the total benefits were lower than the total costs. It’s important to note that societal economic profitability is not the same as corporate profitability. In a societal economic analysis, all advantages and disadvantages, including those not traded in a market, must be accounted for, in accordance with the government’s guidelines for impact assessments. [REMOVE]Fotnote: The Government’s Guidelines for Impact Assessments (2016). Established by Royal Decree on February 19, 2016, under the authority of the instructional power. Presented by the Ministry of Local Government and Modernization. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/instruks-om-utredning-av-statlige-tiltak-utredningsinstruksen/id2476518/

Examples of such goods and costs may include natural resources, greenhouse gas emissions, and skill development.

However, the value of potential learning effects from Hywind Tampen was not quantified in the analysis. With a sufficiently high estimate for the knowledge-building resulting from the project, the socio-economic profitability could have shifted from negative to positive.

Costs and production

The project ultimately ended up costing around 7.4 billion NOK, following budget overruns of nearly 50 percent. There were multiple reasons why the project became so expensive. Floating offshore wind is inherently more complex to set up, and therefore more costly than fixed-bottom offshore wind.

Additionally, Hywind Tampen was built during a period of rising interest rates, increasing inflation, and a weakening Norwegian krone. All three factors contributed to higher project costs. A weak krone makes imported components more expensive, while higher interest rates make it harder to secure capital for development. Higher interest rates also raise the required rate of return because there is more profit to be made by investing money elsewhere. As a result, rising interest rates create more impatient markets, which particularly impacts investments with high upfront costs and long-term payoffs—such as offshore wind.

The turbines are expected to produce around 384 gWh per year, equivalent to the energy production of Norway’s 93rd largest hydropower plant. This will cover about 35 percent of the energy needs of the five platforms (Gullfaks A, B, and C, as well as Snorre A and B).

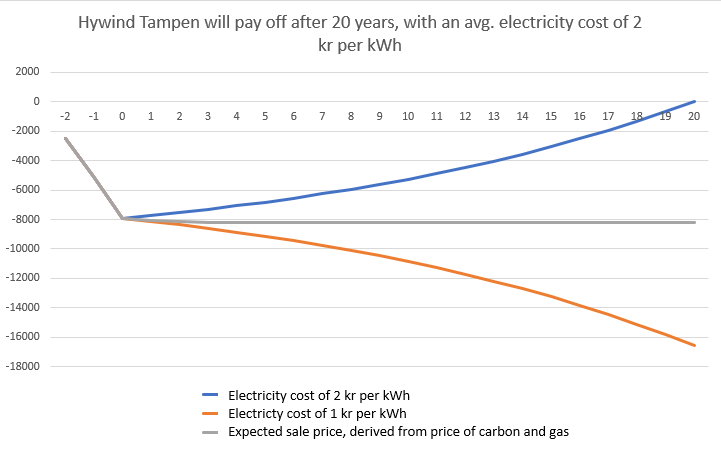

A rough calculation based on the actual development costs and expected operating costs shows that the project could break even after 20 years if the electricity is sold at an average price of two NOK per kWh. This calculation is based on an annual return requirement of 7 percent, as outlined in the Plan for Development and Operation (PDO). However, this excludes the costs related to decommissioning.

The electricity from Hywind Tampen is not fed into the power grid, which makes it a bit more complicated to determine its value. Instead, the value must be calculated based on how much Gullfaks and Snorre save or earn by using electricity instead of gas at the facilities, allowing them to send more gas to the continent. Since 2015, Norwegian gas has been sold at an average price of 0.35 NOK per kWh.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sokkeldirektoratet. Hentet (5. April. 2024) fra https://www.norskpetroleum.no/produksjon-og-eksport/eksport-av-olje-og-gass/ In addition, the licenses save money by avoiding the cost of CO2 taxes and emission allowances when they don’t burn the gas. The value of these CO2 cuts (200,000 tons per year according to Equinor) is 0.90 NOK per kWh in 2023 and will gradually increase to 1.25 NOK per kWh by 2043. This is a very high number, due to the fact that oil and gas projects pay both for emission allowances and a national CO2 tax. As a result, a kWh of Hywind Tampen electricity is estimated to be worth around 1.25 NOK (0.90 + 0.35) in 2023 and 1.60 NOK in 2043. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Vedlegg – Nedbetalingstid Hywind Tampen https://nomus2.sharepoint.com/:x:/r/sites/Gullfaks/Delte%20dokumenter/General/Kilder/Olegreier/Nedbetalingstid%20Hywind%20Tampen.xlsx?d=w33ea2c45fab14435b4633912efc1b76f&csf=1&web=1&e=hNJ3wi

The figure below shows the profitability development of Hywind Tampen, based on different assumptions about electricity prices. Given the expected sales price, the revenues from the turbines will be roughly equal to the capital costs associated with building the facility, meaning the project will not pay for itself.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Vedlegg – Nedbetalingstid Hywind Tampen https://nomus2.sharepoint.com/:x:/r/sites/Gullfaks/Delte%20dokumenter/General/Kilder/Olegreier/Nedbetalingstid%20Hywind%20Tampen.xlsx?d=w33ea2c45fab14435b4633912efc1b76f&csf=1&web=1&e=hNJ3wi Note that the overview shows the payback period for the project itself, not the payback period from the company’s perspective.

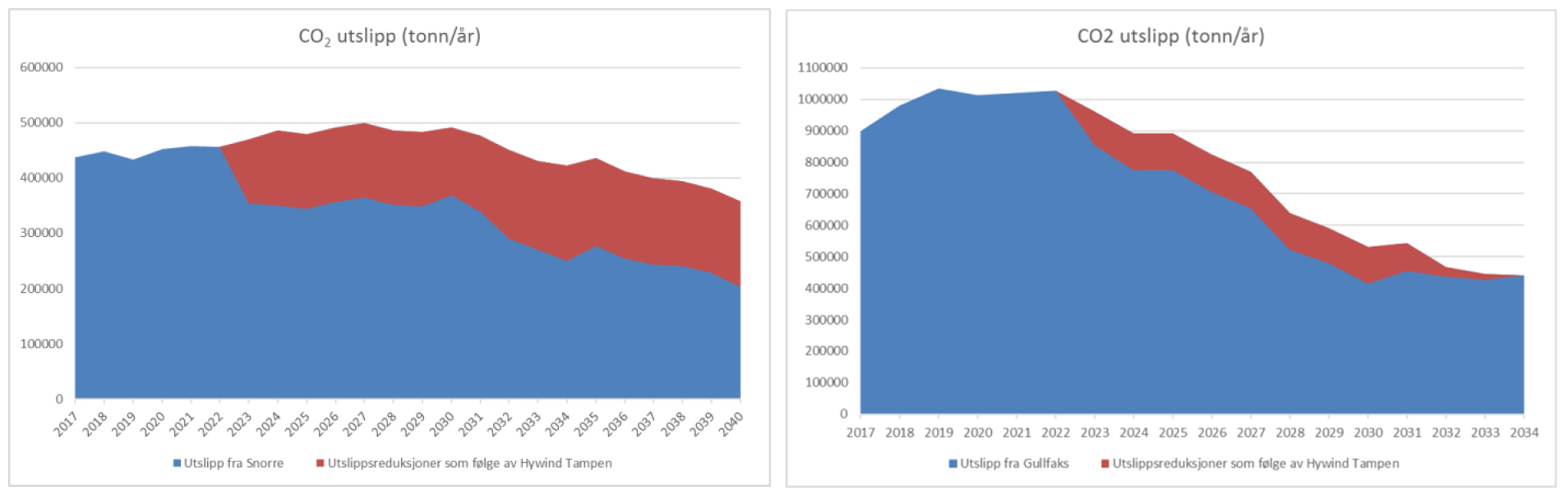

Since the electricity from the turbines replaces energy from gas turbines, Equinor estimates that Hywind Tampen will reduce emissions from Gullfaks and Snorre by 200,000 tons of CO2 and 1,000 tons of NOx annually. This is equivalent to the emissions of just over 18,000 average Norwegians in 2020 (based on consumption).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Helle, K. E. (2020, 18. februar). Hva får jeg for et tonn CO2? Fremtiden i våre hender. Hentet fra https://www.framtiden.no/tips/hva-faar-jeg-for-et-tonn-co2

The situation becomes more complicated when considering that the oil and gas industry is regulated under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). Under this system, emission reductions free up emission allowances, which can result in increased emissions elsewhere. According to the Ministry of Finance’s analysis in the 2024 Perspective Report, subsidies that reduce emissions in sectors covered by the ETS, such as most of the industry, allow these freed-up quotas to be used in other parts of the system, potentially leading to an equivalent increase in emissions in those areas.

[REMOVE]Fotnote: Regjeringen. (2023–2024). Perspektivmeldingen 2024: Meld. St. 31 (2023–2024) (Boks 7.7). https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-31-20232024/id3049290/?q=Boks&ch=7#kap7-6-2

The actual emission reductions, across Europe as a whole, are therefore non-existent or at least significantly lower than 200,000 tons. For the initiative to have an impact on Europe’s overall emissions, the reductions at Gullfaks and Snorre would need to be followed by the EU actively destroying emission allowances.[REMOVE]Fotnote: EU ETS har en mekanisme (Market stability reserve – MSR) som åpner for at slike kvoteuttak kan forekomme dersom det er et stort tilbudsoverskudd i markedet.

This concept might seem a bit cryptic, but it can be illustrated with the following example: Imagine a family of four wants to reduce their electricity consumption, and they’ve agreed that together, they can only shower for a total of 10 minutes each day. Each family member is given their own “shower quota” of 2.5 minutes daily. However, they can trade these quotas amongst themselves—“you can have my shower quota today if you vacuum.” Little brother decides to reduce his shower time to just one minute on average each day. He trades his leftover quotas with other family members. Little brother’s decision has no impact on the total amount of shower time in the household. The only thing that can reduce it is if the family council lowers the overall showering limit.

To the extent that the project has a climate impact, it is because the electricity from Hywind Tampen allows the gas that would otherwise have been used on the platforms to be exported to the European market instead.

It may seem counterintuitive that the increased gas exports—rather than the emission reductions on Gullfaks and Snorre themselves—are what could potentially have a climate impact. The reason is that, as of 2024, gas has a lower emissions intensity than the rest of the European energy mix.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rystad Energy. (2023, 15. februar). Netto klimagassutslipp fra økt olje- og gassproduksjon på norsk sokkel [Rapport]. Hentet fra https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/f5fc522f50674c1f9e0b5db47c264dbe/netto-klimagassutslipp-fra-okt-olje-og-gassproduksjon-pa-norsk-sokkel_hovedrapport.pdf

According to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, the power supply was not expected to affect the total petroleum production of the fields.

To the extent that Gullfaks and Snorre gas displaces more emission-intensive energy sources in Europe, this could result in a net climate benefit. However, this benefit could be partially or entirely offset by the fact that the emission reductions occur within the EU’s emissions trading system, potentially freeing up emission allowances elsewhere in Europe.

If the EU succeeds in developing an energy system with lower average emissions per kWh than gas, the climate impact of increased Norwegian gas exports could shift from positive to negative.