Gullpipe plan abandoned

In March 1981, Statoil submitted an application to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy to transport oil from the Gullfaks platform via buoy loading. In the letter to the ministry, Statoil outlined the possibility of constructing an oil pipeline but concluded that the costs of the pipeline were not justified by the potential benefits.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 28 https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True In October of the same year, Parliament approved buoy loading as the permanent solution for bringing oil from Gullfaks ashore.

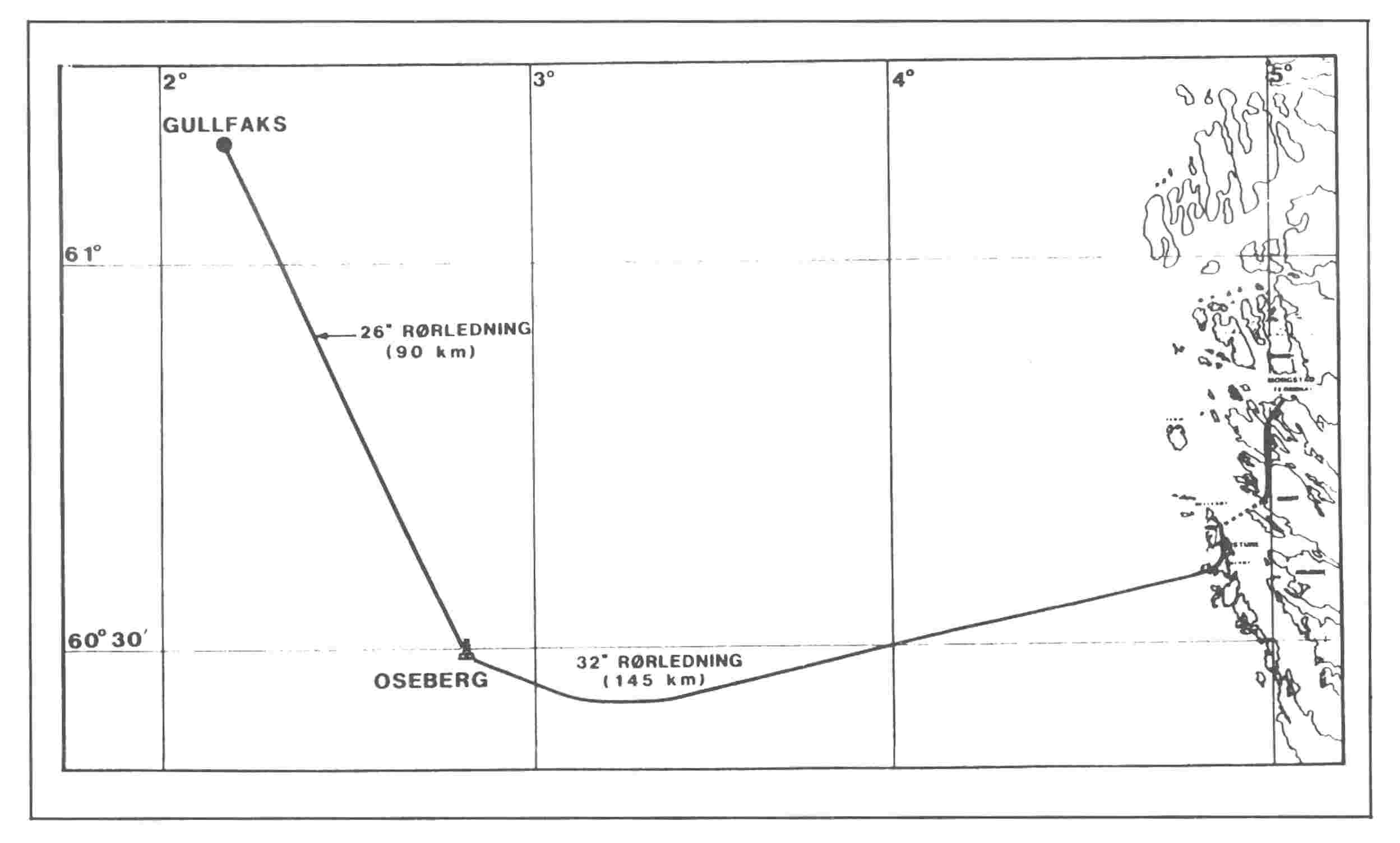

In December 1983, two years after the buoy loading application had been approved, Statoil changed its mind. Statoil and Norsk Hydro joined forces and submitted a new application to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, proposing to build an oil pipeline from Gullfaks and Oseberg to Mongstad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 1. https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True By this point, significant investments had already been made in oil storage facilities on the platform, the construction of tankers for transport, and other infrastructure supporting buoy loading.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 29 https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True

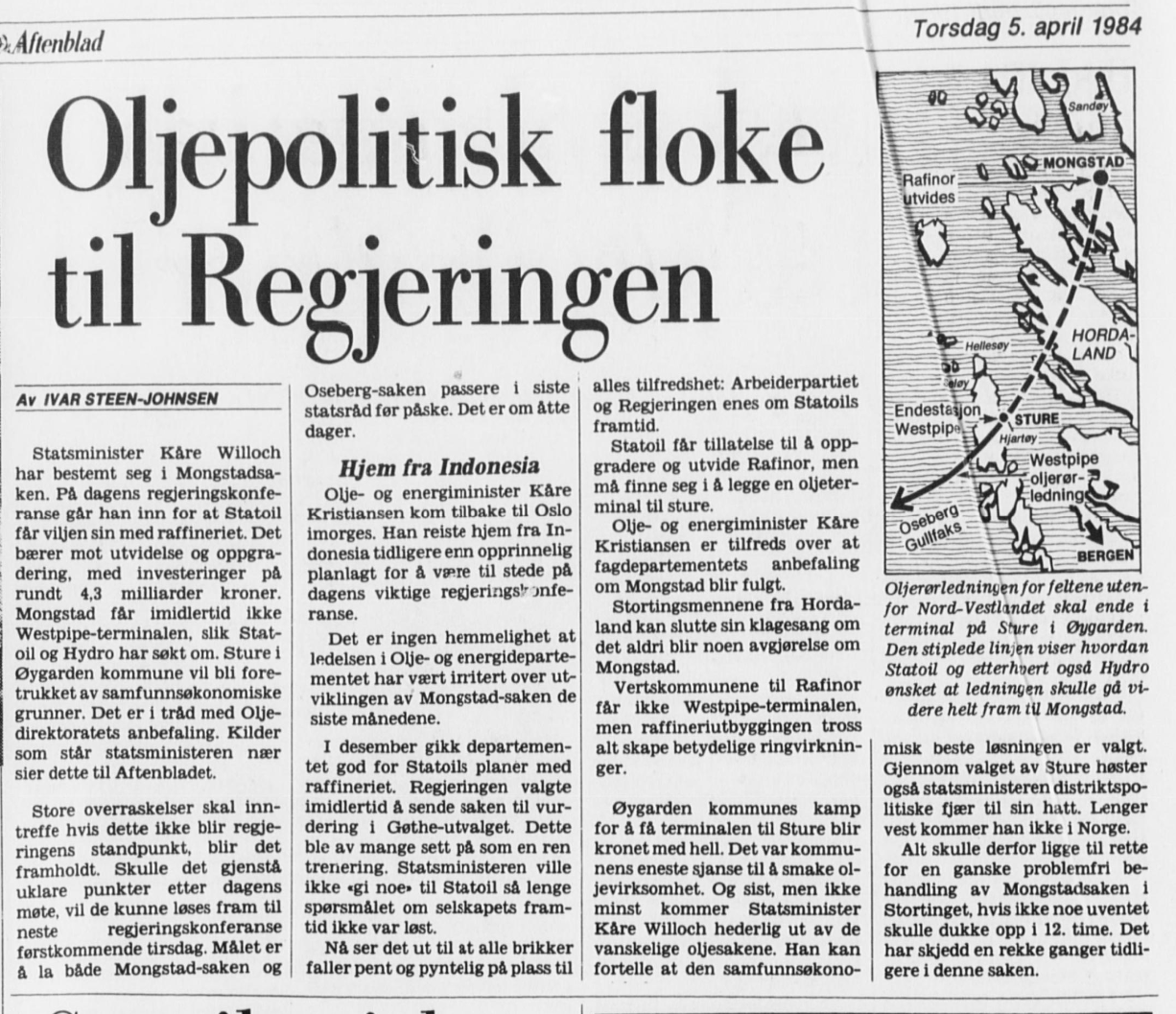

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy did not view the new proposal favorably, and it was ultimately rejected by Parliament in the spring of 1984. Instead, Parliament approved an oil pipeline from Oseberg to Hydro’s crude oil terminal at Sture. This decision was a setback for Statoil.

Why did Statoil want a joint oil pipeline from Oseberg and Gullfaks?

A key reason for Statoil’s change of heart was Hydro’s decision in 1983 to build its own oil pipeline from Oseberg to a crude oil terminal at Sture. Sture was closer to the Oseberg field than Mongstad. Although Hydro operated Oseberg and Statoil operated Gullfaks, Statoil was the majority owner of both fields. Statoil did not want its Oseberg oil to be tied exclusively to Hydro’s crude oil terminal at Sture.

[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thommasen, E. (2022). Middel og mål Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget, s. 191.Statoil’s desire for a joint oil pipeline from Oseberg and Gullfaks to Mongstad was largely a response to Hydro’s proposal.

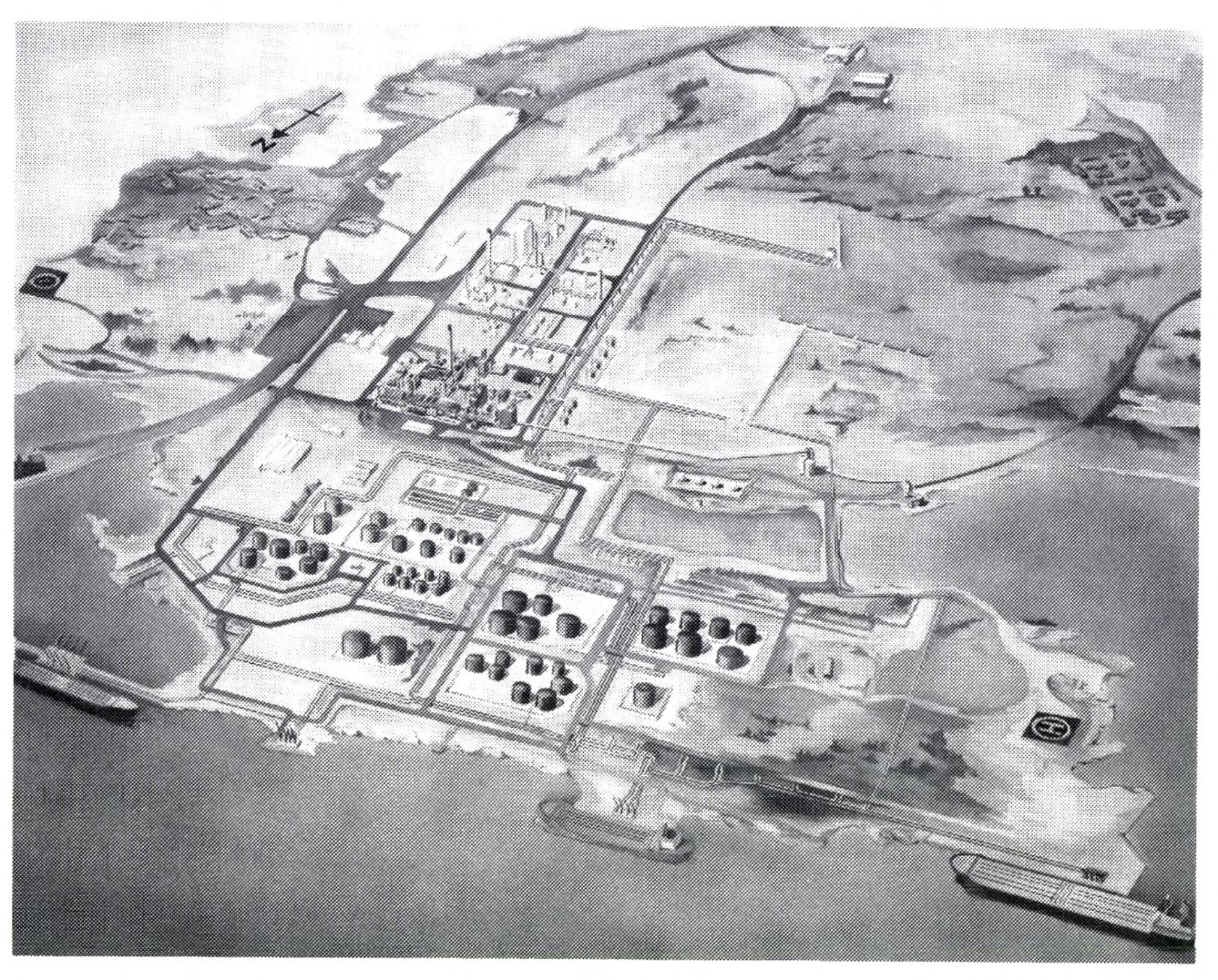

Statoil also had ambitious plans to expand capacity at Mongstad. Investing in the terminal was part of a broader strategy to become more involved in the petrochemical industry and the processing and sale of petroleum. A joint oil pipeline from Gullfaks and Oseberg to Mongstad would further establish Mongstad as a central hub and justify a significant increase in the terminal’s capacity.

Why Did Hydro Agree to the Proposal?

To secure the support of Hydro and the other licensees in Gullfaks and Oseberg (Saga, Elf, Mobil, and Total) for the Gullpipe proposal, Statoil took on a larger share of the project’s financial risk.

On December 3, 1983, the parties reached an agreement in which Statoil committed to covering any potential cost overruns. Additionally, Statoil agreed to cover Hydro’s costs related to the transport of Oseberg oil if Gullpipe was delayed. Statoil estimated that the pipeline would be operational by fall 1988, while Hydro projected it would be ready by fall 1989. The agreement stipulated that if the pipeline wasn’t in operation by January 1, 1989, Statoil would be financially responsible for the transport of Hydro’s Oseberg oil.

[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 23 https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True

In a scenario where delays in the Gullpipe project forced Oseberg to reduce production, Statoil would have been responsible for covering the resulting financial losses.

Statoil made enough concessions to get Hydro on board with the proposal, but Hydro’s support was somewhat reluctant. Hydro did not hide the fact that they still believed the Oseberg-to-Sture pipeline was the better option. According to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy’s parliamentary proposition, Hydro remained skeptical of Statoil’s optimistic estimates for the project’s profitability.

[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thommasen, E. (2022). Middel og mål Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget, s. 194.

It’s interesting that Hydro found the Gullpipe solution favorable enough to back the proposal, yet at the same time, they were open about their more pessimistic estimates for profitability and timelines. This dual attitude suggests that Hydro, in the end, might have been relatively indifferent between the two options.

Why didn’t the Ministry support Gullpipe?

In the parliamentary proposition, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy noted that they “viewed it as unfortunate that this landing alternative was based on unilateral guarantees from Statoil.” The fact that Statoil had to assume such significant risk to bring the other companies on board was a red flag, and it’s no surprise the ministry was wary of the agreement. If Gullpipe had been profitable from a business perspective, there shouldn’t have been a need for Statoil to shoulder the risk for the other license holders.

Additionally, the oil pipeline was expensive. The pipeline between Oseberg and Gullfaks alone was estimated to cost 830 million NOK. The total price tag for the project was 4.26 billion NOK—twice the cost of landing Oseberg oil at Sture. On the other hand, continuing with buoy loading from Gullfaks would involve higher operational costs than a pipeline. The ministry concluded that the Oseberg-to-Sture solution was more economically viable than Statoil’s Gullpipe proposal. [REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 32 https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True

It’s worth noting that interest rates were very high throughout the 1980s, which significantly affected how the market weighed future costs and revenues. Gullpipe involved a large upfront cost in exchange for consistently lower operational costs in the future. High interest rates made the market place more emphasis on the “here and now,” which reduced the net present value of projects like Gullpipe compared to buoy loading. In its cost calculations for the different alternatives, Statoil used a discount rate of 7 percent.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 109 (1983-84) – Utbygging av Osebergfeltet, ilandføring av olje til Norge og etablering av en råoljeterminal m.v. s. 27 https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1983-84&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL499&s=True

That rate was significantly lower than the market interest rates at the time and in the following years.

Caught Statoil by surprise

About six months before the parliamentary review, it seems that Statoil’s board almost assumed the oil pipeline would be approved. In February 1984, Statoil’s board announced in its internal newsletter that after 1989, there would no longer be a need for shipping oil from Gullfaks, as the pipeline would be operational by then.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status: internavis for Statoil-ansatte. (1984). Nr. 3, s. 2. Status (Statoil : norsk) : internavis for Statoil-ansatte. 1984 Nr. 3 (nb.no) On February 7 of the same year, the companies in the Gullfaks and Oseberg licenses signed a new agreement regarding the name of the oil pipelines. They agreed to apply to the authorities for permission to use the name “Westpipe” for the pipeline network that would run from Gullfaks, via Oseberg, to Mongstad.

Despite their confidence, the oil pipeline was halted in 1984 by the Willoch government. As a consolation, the same parliamentary proposal included plans to expand the capacity of the Mongstad facility to process buoy-loaded oil.

However, the pipeline was revisited and eventually realized a few years later as part of the Troll field development.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B. V. (2006). Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet. Statoil, 92.

Quality Assurance Award to Gullfaks AConstruction of the A shafts in Gandsfjorden