Gullfaks comes «home»

In 2001, Statoil was allowed to buy back some of the license shares it had lost to the state during the “wing-clipping” of 1984. While the original downsizing was justified by concerns that Statoil had grown too large, the 2001 SDFI sale was based on the argument that the company was too small. In reality, it was not Statoil’s size that had changed, but rather the scale of the industry it operated in.

By Norwegian standards, Statoil was still a giant, but globally, it remained a relatively small player. The company’s board argued that stronger financial backing was needed for its stock market listing and international expansion to succeed.

SDFI as a Dowry

Statoil’s partial privatization had been in the works for some time. As the government prepared to reduce its stake in the state oil company, it naturally wanted to maximize the value of Statoil’s shares.

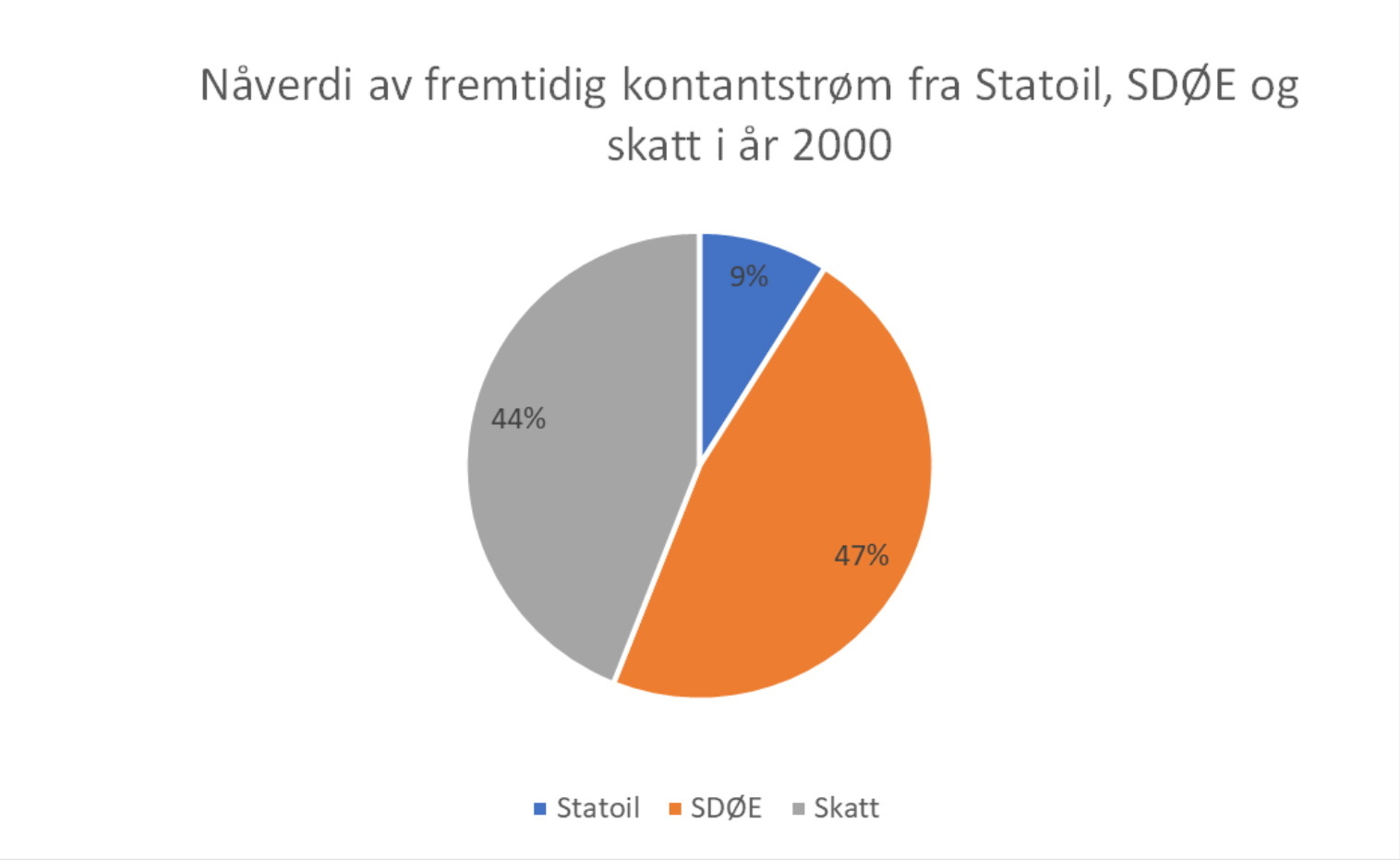

Here, the transfer of SDFI assets could play a crucial role. At the time, the state’s projected SDFI revenues were about five times larger than the expected future dividends from Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001). Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 16.

By transferring parts of the SDFI portfolio to Statoil ahead of the stock listing, the company’s shares would become more valuable. A Statoil share would yield higher dividends if the company owned larger stakes in more licenses, making the shares more attractive to investors.

At first glance, such a transfer might seem like a zero-sum game—simply moving value from one state asset to another. In theory, increasing Statoil’s value should be offset by a corresponding decrease in SDFI’s value. It’s comparable to selling your apartment fully furnished with designer furniture to increase its price, rather than selling the apartment and furniture separately.

However, Statoil argued that selling SDFI shares to the company before the stock market listing would create a net gain—meaning the increase in Statoil’s value would outweigh the reduction in SDFI’s value. In its proposal to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, Statoil claimed that transferring SDFI shares would increase the value of the state’s petroleum wealth while reallocating part of it into financial assets.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001). Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 30.At oljeformuen plasseres i «finansielle aktiva» vil si at den investeres i ulike verdipapirer, som over tid vil ha en mer stabil verdi enn olje og gass. Når Norge henter opp olje og gass, selger den, og setter pengene inn i oljefondet, omgjør vi i praksis petroleumsressurser til finansielle aktiva. Det gjør oss over tid mindre eksponert for svingninger i olje- og gasspriser.

Why Did Statoil Push for the SDFI Sale?

Statoil’s board argued that most, if not all, of SDFI should be transferred to the company before the stock listing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001). Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 30. The ministry did not agree to such a large transfer but ultimately allowed Statoil to purchase (not receive for free) 15% of the SDFI portfolio.

Two key arguments from Statoil stood out in favor of the sale:

- Industry Consolidation and Global Competition

The oil industry had undergone major changes leading up to the stock listing. Between 1998 and 2000, large international companies had grown even bigger through mergers and acquisitions, leading to increased market dominance by a few global giants.

In its proposal to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, Statoil emphasized that, in this new competitive environment, it had become a small player—both financially and in terms of reserves and production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001). Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 29.

To compete on a global scale, Statoil needed more capital. This could be achieved through acquisitions or a merger with another company, as suggested by Ove Gusevik, director at investment firm First Securities.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Erikstad, T. (16.09.1999). Statoil bør kun selge ti prosent. Dagens Næringsliv. Another option was for Statoil to bring part of the SDFI portfolio with it as it transitioned into a publicly traded company.

2. More Efficient Resource Management

Statoil also argued that increasing the ownership stakes of operating companies would lead to economies of scale and coordination benefits.

In other words, the state would benefit if key companies on the Norwegian continental shelf held larger shares in important resource areas where they were already operators.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001). Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 31 Greater ownership stakes would reduce exploration, development, and operational costs by improving cooperation across licenses and optimizing infrastructure use. This, in turn, would generate higher tax revenues and increase state earnings where it remained a direct owner.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.prp. nr. 36 (2000-2001) Eierskap i Statoil og fremtidig forvaltning av SDØE, s. 31

Statoil specifically highlighted the Tampen area, which includes Gullfaks, as a region where reducing SDFI’s share and increasing operator stakes could lead to better resource utilization.

The Largest Deal in Norwegian History

These arguments resonated with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, which agreed to Statoil’s request.

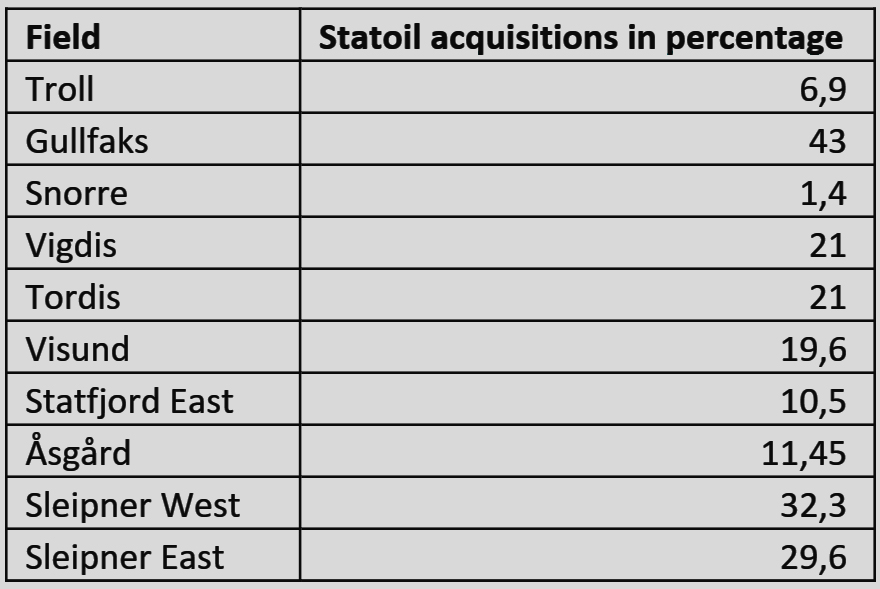

On May 3, 2001, Minister of Petroleum and Energy Olav Akselsen (Labour Party) and Statoil CEO Olav Fjell announced the details of the deal between Statoil and the ministry for the sale of SDFI shares. Statoil ultimately paid 38.6 billion NOK to acquire 15% of SDFI, increasing its petroleum reserves by 50%.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nedrebø, R. (04.05.2001). Fjell-stø tro på milliardkjøp. Stavanger Aftenblad. Gullfaks was among the licenses where Statoil spent the most to increase its stake.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Grande, A. (2001, 4. mai). Statoil betaler 38,6 milliarder for 15 prosent av SDØE. Dagens Næringsliv. The table below shows the ten largest individual transactions between the state and Statoil.

Gullfaks Comes “Home”

Statoil had argued that operations in the Tampen area would become more efficient if field operators (or other license holders) held larger ownership stakes. This is reflected in the fields where Statoil prioritized increasing its share. Six of the ten fields where Statoil made its largest acquisitions—Gullfaks, Snorre, Vigdis, Tordis, Visund, and Statfjord East—were in the Tampen area.

The largest percentage increase occurred in the Gullfaks license. Statoil’s ownership rose from 18% to 61%, while SDFI’s share fell from 73% to 30%. During the wing-clipping of 1984, Gullfaks had been the field where the state took the strongest position—Statoil’s ownership had dropped from 85% to just 12%. After 2001, the company was once again the majority owner of the license.

Statoil’s increased ownership of Gullfaks was not without controversy. In Dagens Næringsliv on September 28, 1999—three months before Saga Petroleum exited the Gullfaks license—Saga engineer Ivar Haaland argued that the state should prioritize selling SDFI shares in Gullfaks to a foreign company. He believed that bringing in a major international player with expertise in enhanced oil recovery could improve decision-making and avoid deadlocked processes.

This recommendation went unheard. It was not until 2013—12 years later—that the license saw a new partner, when Statoil sold 19% of Gullfaks to the Austrian company OMV.