Gullfaks C moves up in the queue

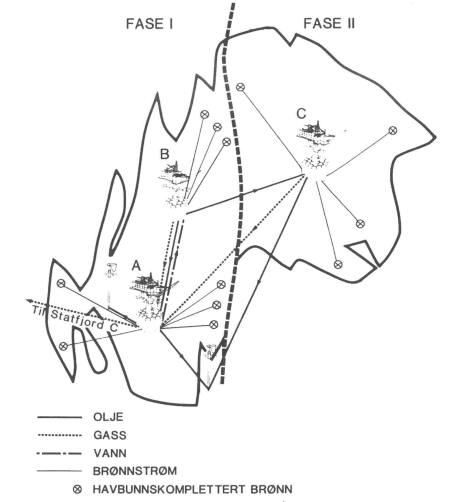

On February 8, 1985, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy received an application from Statoil, Hydro, and Saga to develop Gullfaks Phase II. This involved installing a third Condeep platform (Gullfaks C) on the eastern part of the main reservoir..[REMOVE]Fotnote: Alsaker, S. (1985, 7. juni). Forhandlinger i Stortinget nr. 314. Utbygging av Gullfaks fase II m.v. Stortinget, s. 4631. https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1984-85&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL708&pgid=c_1109Two months later, the plans were approved. Gullfaks C was a welcome project at a time when the British authorities had put the Sleipner project on hold.

Gullfaks Phase I, which included the development of the A and B platforms on the western part of the reservoir, was approved by the government in October 1981. At that time, the Norwegian Parliament required the licensees to return with a plan for Phase II at a later date. That plan was presented in January 1984.

The plan did not specify when development would begin but placed Gullfaks C in a project reserve, ensuring the authorities had nearly ready-to-develop fields available in case of market capacity. Statoil understood that Gullfaks C could be initiated on short notice if supplier market capacity became available.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil. (1984). Status: internavis for Statoil-ansatte (Nr. 3, s. 3).

In other words, it had long been anticipated that the Gullfaks license would extract oil from the eastern part of the reservoir. However, it was less expected that the government would give the green light as early as March 1985. The main reason for accelerating the plans was the pause on the Sleipner project.

Backup-Sleipner

The plan was for the Sleipner gas and condensate field to start production in 1991. Margaret Thatcher’s government ensured that this didn’t happen. Since 1982, Statoil had been negotiating with the state-owned British Gas Corporation (BGC) for an agreement on the purchase and sale of Sleipner gas. The deal was not approved by British authorities. Additionally, on February 10, 1985, the British announced that they had revised their gas reserves upward and no longer saw an immediate need for more Norwegian gas.

[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stortinget. (1985). St.prp.nr. 86 (1984-85): Utbygging av Gullfaks fase II (s. 20). https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1984-85&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL524&pgid=b_0417

The development of Sleipner would have involved investments of around 42 billion NOK in 1984 prices (adjusted to 123 billion NOK in 2022 prices). With Sleipner temporarily on hold, the challenge was to find other projects to maintain activity levels in the supplier industry.

This situation illustrates a key trade-off that governments in an oil-based economy face: the state must always try to balance projects so that activity levels do not become too high or too low. Periods of sudden project droughts can leave scarce resources like shipyard capital and labor unused. On the other hand, periods of excessive activity can drive up prices, lead to overinvestment, and shift profits from oil companies (which pay economic rent tax) to suppliers (who do not). In other words, resources are best utilized when the flow of new projects remains relatively steady.

Gullfaks C as a balancing field

In such a balancing act, Gullfaks C was well-suited as a stabilizing tool. The reason was that Gullfaks C could quickly move from the drawing board to the shipyards. The platform would be an almost identical copy of Gullfaks A, which meant the design phase took less time. Thus, the government could use Gullfaks Phase II to compensate for the sudden loss of other projects.

Gullfaks C was a good candidate, though by no means a perfect replacement for Sleipner. Phase II was estimated to cost just under half the amount of Sleipner (19.2–19.4 billion NOK).

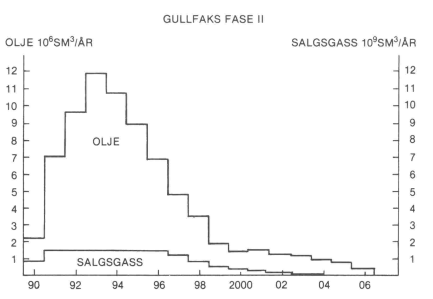

[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stortinget. (1985). St.prp.nr. 86 (1984-85): Utbygging av Gullfaks fase II (s. 10). https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1984-85&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL524&pgid=b_0417However, while the Sleipner license had faced significant challenges in securing a gas sales agreement, Gullfaks C was guaranteed from the start. The buyers of the gas from Gullfaks A and B (Phase I) were already committed to receiving the gas from Gullfaks Phase II.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stortinget. (1985). St.prp.nr. 86 (1984-85): Utbygging av Gullfaks fase II (s. 8). https://www.stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Stortingsforhandlinger/Lesevisning/?p=1984-85&paid=2&wid=b&psid=DIVL524&pgid=b_0417However, even without such an agreement in place, the Gullfaks license would likely have managed to secure a gas sales deal, due to the relatively modest gas reserves in the field overall. As shown in the figure below, Gullfaks C, like A and B, was primarily an oil field.