From Statoil to the State

In 1984, the Willoch government secured broad support in Parliament for a restructuring that transferred a large portion of Statoil’s holdings on the Norwegian Continental Shelf to a new, state-owned portfolio known as the State’s Direct Financial Interest (SDFI). This transfer — often referred to as “clipping Statoil’s wings” — was partly motivated by concerns that allowing Statoil to manage too much of the country’s petroleum wealth could lead to overinvestment and company empire-building, potentially at the expense of broader public interests.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Krogh, F. (2021). Vingeklippingen av Statoil. Norsk Oljemuseum Årbok, 42. Redirecting a larger share of cash flow directly to the state was seen as a way to ensure a more coherent and accountable approach to the use of oil revenues.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thommasen, E. (2022). Middel og mål: Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget

85 percent public ownership

Among all fields on the shelf, Gullfaks was where the state took the most substantial ownership share through the SDFI.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.meld. 21. (1992). Statens samlede engasjement i petroleumsvirksomheten i 1992 (S. 34). Initially, the Gullfaks license was divided among Statoil (85 percent), Hydro (9 percent), and Saga (6 percent). In 1985, 73 percent of Statoil’s share was transferred to the SDFI, leaving Statoil with just 12 percent ownership.

Following the Statoil reform, the ownership distribution was: Statoil with 12 percent, Hydro with 9 percent, and Saga with 6 percent. This arrangement aligned with the Willoch government’s goal of creating a more balanced distribution among the Norwegian participants. The non-socialist parties had proposed that, in licenses involving only Norwegian actors such as Statoil, Hydro, and Saga, the companies should have relatively equal shares — not taking into account income and expenses allocated to or covered by the state.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Innst. S. nr. 87 om St. Meld. Nr 33 (1984.85)

The Labour Party objected to this approach and responded with a different proposal, suggesting that the state’s total stake should be equally divided between Statoil and the state itself.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rommetvedt. H. (28.02.1991) Butikk eller politikk? Statoils roller i norsk oljevirksomhet. Rogalandsforskning Stavanger. S 33.

Had the Labour Party’s version been adopted, Statoil would have held more than 40 percent of the license, becoming an equal partner with the state while still holding a far larger share than Hydro or Saga. Instead, the result was that Hydro and Saga combined ended up with a larger stake in Gullfaks than Statoil.

A long path to positive returns

In the short term, the creation of the SDFI had a positive impact on Statoil’s bottom line.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status: internavis for Statoil-ansatte 1985 nr 1. s.3 Many of the fields transferred to the state were still under development and had not yet begun generating profits. By taking over direct ownership in these licenses, the state assumed responsibility for its share of both past and future investments — in exchange for a corresponding share of the revenues once production began.

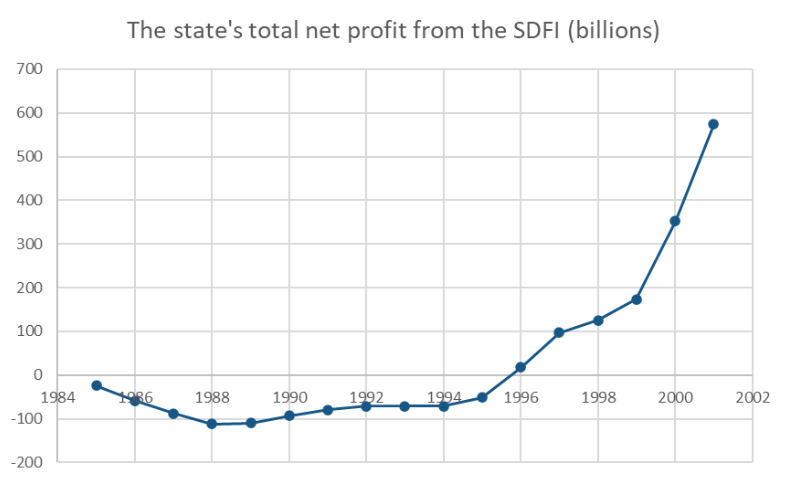

As a result, the SDFI operated at a loss for several years. The graph below shows the cumulative financial result of the SDFI portfolio from its inception in early 1985 through 2001. It wasn’t until 1996 — eleven years later — that the state’s cumulative revenues from the portfolio exceeded its total expenditures.

Gullfaks: An expensive shift for the state

The shift in ownership structure for Gullfaks was costly for the state in the early years — though the field would go on to become a key contributor to SDFI revenues.

At the beginning of 1985, investments in Gullfaks totaled NOK 9.3 billion (equivalent to nearly NOK 30 billion in 2022 terms). With the state now holding 73 percent, it had to cover a proportional share of those investments — meaning transfers of more than NOK 20 billion to Statoil, Hydro, and Saga.

It wasn’t entirely clear how such large reimbursements should be handled.

For Gullfaks, Oseberg, and Heimdal alone, Statoil demanded that the state reimburse more than NOK 10 billion in 1984 money.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1984, 20. august). Statoil og staten i milliard-oppgjør. Stavanger Aftenblad, s. 7.These repayments — along with ongoing investment commitments — led to four consecutive years of SDFI deficits, and it took more than a decade before the state’s cumulative cash flow from the portfolio turned positive.

Statoil Moves into SandsliModules for Gullfaks A