From SPM to OLS

For as long as the Gullfaks field has produced oil, the crude has been shipped to shore by vessels – so‑called shuttle tankers. Today, oil is offloaded from the field by a subsea loading system, but for many years the job was done via two highly visible loading buoys.

SPM1 and SPM2

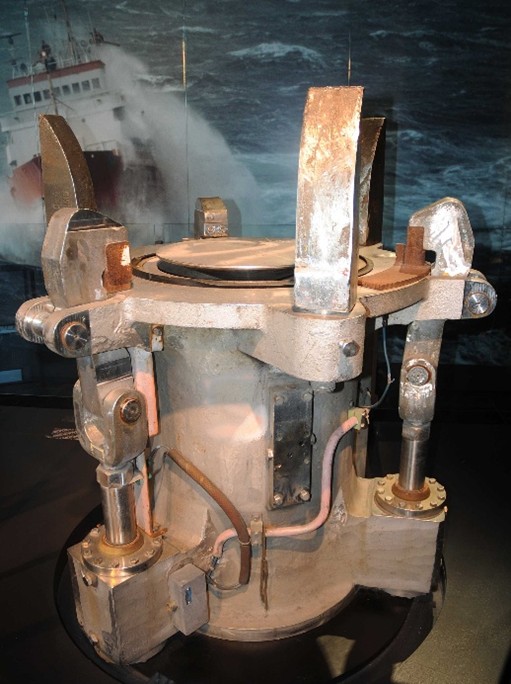

SPM stands for “single point mooring,” i.e., a single mooring point. The loading buoys were anchored to the seabed, with a structure that projected above the sea surface. More like loading towers than buoys, writes John Ove Lindøe in his book From sea to shore : the shuttle tanker story.[REMOVE]Fotnote: John Ove Lindøe, From sea to shore : the shuttle tanker story (Stavanger: Wigestrand Forlag and Stavanger Sjøfartsmuseum, 2009), 88

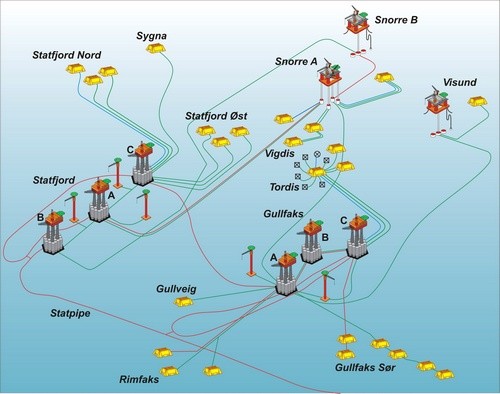

SPM1 was installed in 1986, 2.4 km northwest of Gullfaks A. SPM2 was installed in 1987, 2.4 km southeast of Gullfaks B. SPM1 was connected by pipeline to the storage cells on Gullfaks A, while SPM2 was connected to both Gullfaks A and Gullfaks C. Gullfaks B sent – and still sends – its oil to one of the other two platforms.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Equinor, “Gullfaks sikter mot 2040 med nye lastesystemer,” https://www.equinor.com/no/news/archive/2014/06/04/04JunGullfaks

The buoys were clearly visible above the surface. Each had a helideck and, beneath it, a converted container that served as living quarters. This is how Jan Moe describes them.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Information from Jan Moe is based on a telephone conversation with Julia Stangeland, February 7, 2025.

From 1987–88 and for about 20 years, Moe worked as a mechanic on Gullfaks A; he later worked on Gullfaks C. He recalls that mechanics on Gullfaks A were responsible for maintenance on both loading buoys, and that he was one of them. He estimates that, per shift, two to three mechanical personnel had this assignment. Others specialized, for example, in cranes or maintenance.

Typical work on the buoys included replacing equipment that, by regulation, had to be swapped after a set interval. There were also inspections due after one or four years. Visits could likewise be required to investigate and resolve alarms or fault reports.

The trip from the platform over to the buoy was done by helicopter—one based on Statfjord, ordered in advance. In bad weather, or if the helicopter was diverted for an emergency response, Moe and colleagues sometimes had to stay overnight on the buoy.

They would then sleep in the container under the helideck, where they could also cook. If the job ran longer, painting or other maintenance, they planned for an overnight. In such cases, someone from operations always came along. They acted as the offshore installation manager (OIM) on board the buoy. The OIM had a few reporting and logging duties but otherwise functioned as the crew’s cook.

Simplified loading buoys

The buoys were simplified in their complexity. The goal was to reduce buoy weight, which in turn reduced the required mooring weight. Simplification also cut maintenance needs. Both factors reduced cost.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Odd Jan Lange, “Ny lastebøye i grundig test. Forenkling av en hovedidé bak Gullfaks-bøyen,” Statoil, 1983, vol. 5, no. 4, 32–34.

The buoys were built by the Norwegian‑French company Articulated Columns Norway (ACN).

Moe notes there was no need to have personnel on board the buoys during offloading to the tankers. If assistance was required, the shuttle tanker’s crew could get help from a standby vessel in the area, boats that rotated between the field’s platforms.

These vessels also delivered goods from the platforms to the buoys when work was scheduled there. Supplies could include both equipment for buoy work and food. The goods themselves reached the field by supply vessel. Equipment arrived in containers and had to be re‑stowed before it could be transferred to the buoy.

As noted, there are strict rules for how long equipment may be used before replacement. In 2014 it was SPM1 and SPM2’s turn to retire.

OLS1 and OLS2 – toward 2040

When the Gullfaks license (Statoil, Norsk Hydro and Saga Petroleum) had to choose an oil offloading system in the 1980s, they picked the same solution then used on the Statfjord field.

Following issues with one of Statfjord’s loading buoys, the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate revised the expected service life for such buoys down from 30 years to between 5 and 15. Despite this, the Gullfaks partners believed the buoys on Gullfaks would be more robust.[REMOVE]Fotnote:Equinor, “Gullfaks sikter mot 2040 med nye lastesystemer.”

They were proved right, but in 2014 the era nevertheless ended.

When the Gullfaks partners (this time Equinor, Petoro and OMV) selected a new system, they again chose the same one used on Statfjord. Equinor notes this on its website, it enables coordination and synergies with the Statfjord field related to operations, maintenance and spare parts.[REMOVE]Fotnote:Equinor, “Gullfaks sikter mot 2040 med nye lastesystemer.”

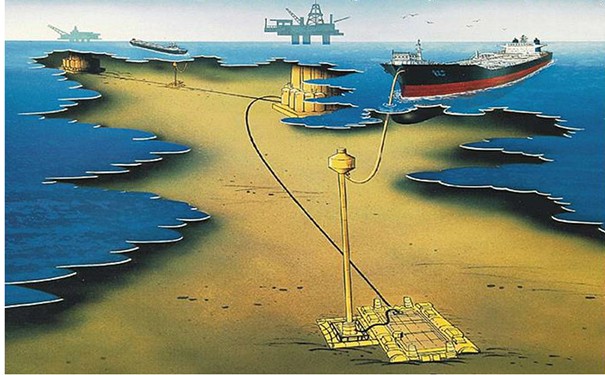

The replacement system is called Ugland‑Kongsberg Offshore Loading (UKOLS), developed by Ugland Engineering and Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk. The system won the innovation award at ONS (Offshore Northern Seas) in 1986 and has been used on the Statfjord field since 1988.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lindøe, From sea to shore : the shuttle tanker story, 88–89.

Unlike the loading buoys, the entire system sits below the sea surface. According to Equinor, it is also simpler to use than the old buoys.

Replacing the old buoys was not only a matter of aging equipment. It also signals that the field’s expected lifetime has been extended by several years. The license holders now aim for the field – or at least the platforms – to keep producing toward 2040. A new oil loading system was therefore needed.

Out on the field, the new loading points are referred to as OLS1 and OLS2. Apparently, “UKOLS1” and “UKOLS2” were a bit of a mouthful.