From Backwater to «Norway’s Oil Capital»

Until the 1970s, Vats (and the surrounding area) was hardly a contender to be

a center for anything beyond itself. From a primary-industry perspective, it

had long been obvious how the local landscape set the terms for making a

living: you farmed the land and maybe fished the fjord.

With industrialization came new ways of seeing nature’s energy potential.

Mountains and fjords

The first chapters of modern Norwegian energy history show how the agrarian

world’s age-old value system could be flipped on its head in short order.

Time and again, the most maligned, steep hillsides beneath sheer cliffs were

turned into cornerstones of the nation’s hydropower supply. Squeezed between

mountain and fjord, today’s “power cathedrals” stand as monuments to that

revolution.

The next chapters in this energy story include the petroleum

industry, which would harness previously untapped natural formations in a

similar way. But now it wasn’t the drop above sea level that mattered, it was

the depth below the surface.

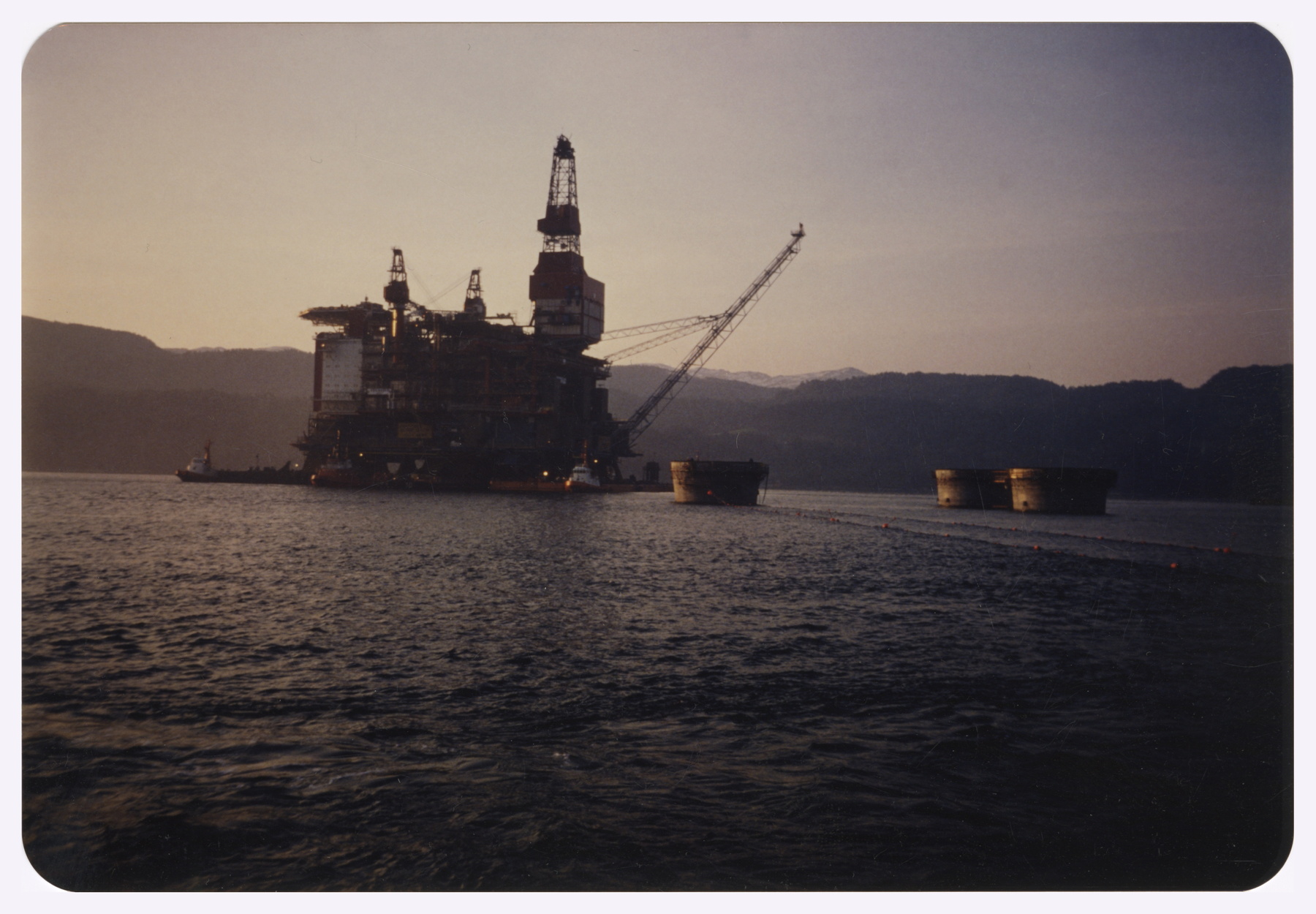

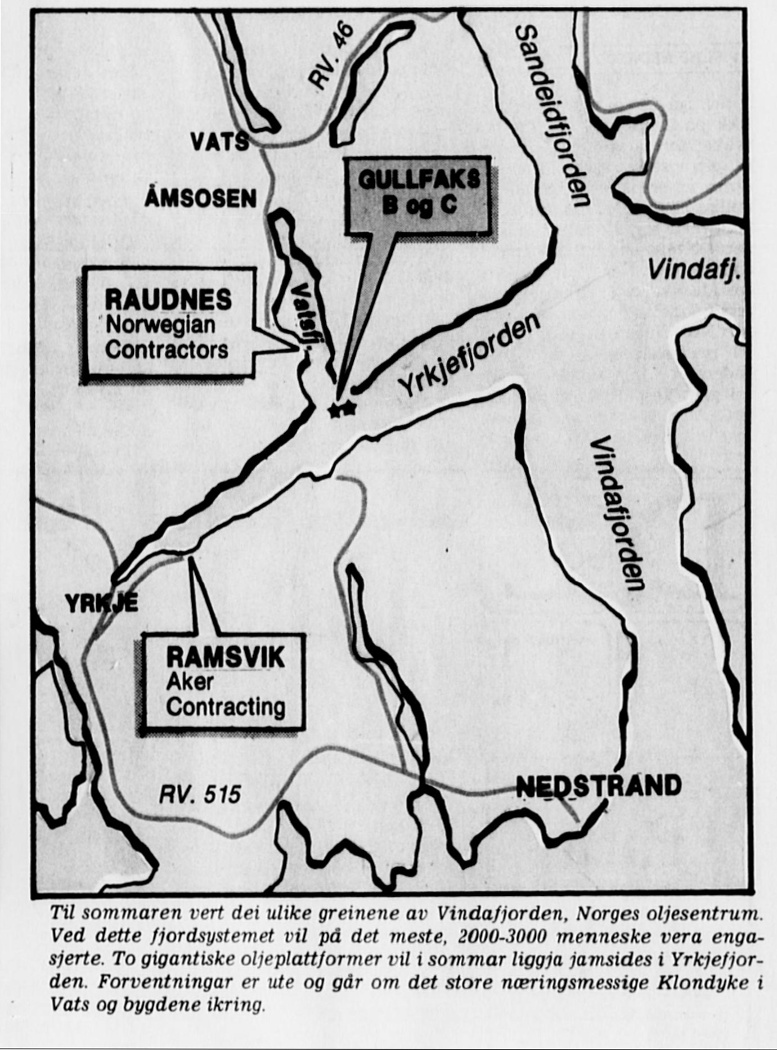

One such place was where the Vatsfjord meets the Yrkjefjord. Here the water is 450 meters deep. The fjords at Vats illuminate how these formations were used to build and assemble some of the largest movable structures the world has seen.

The major Norwegian player in this field was Norwegian Contractors at

Hinnavågen. But Gandsfjorden by Hinnavågen soon became too shallow for the

needs of ever deeper-draught structures. The fjords at Vats thus became “the

extended [fjord] arm of Hinnavågen.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind 1993. På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973-1993. Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, p. 46.

Temporary, yet tremendous

Vats’ link to the concrete era was decidedly temporary—most projects involved

nearly completed concrete gravity-based substructures towed into this fjord

landscape to be mated with the topsides, then towed out to the field. It all

happened over roughly two decades, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s.

Even so, the activity had a major impact on the local community while it was

underway. And never—before or since—would activity be as intense as after the

arrival of Gullfaks B in the spring of 1987, and especially during

construction of the Gullfaks C substructure that same summer.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The concreting works on Trolls understell approximately six years later

employed 900 people on the skaftegliden, split across five shifts. (The

hovedgliden took place in Hinnavågen.) See Førde, Thomas 1994. Varig

verdensrekord sett i Yrkjefjorden. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 30.04.1994,

p. 8. The pressure of

work in those hectic months would earn the area the nickname “Norway’s oil

capital.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas et al. 1987. Historisk sommer: Klondyke i Vats. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 27.03.1987, p. 13.

The Gullfaks B substructure was to be connected to its topsides. The

Gullfaks C job was far more extensive: almost the entire gravity base was cast

in the Yrkjefjord/Vatsfjord (aside from the base section built at Hinnavågen).

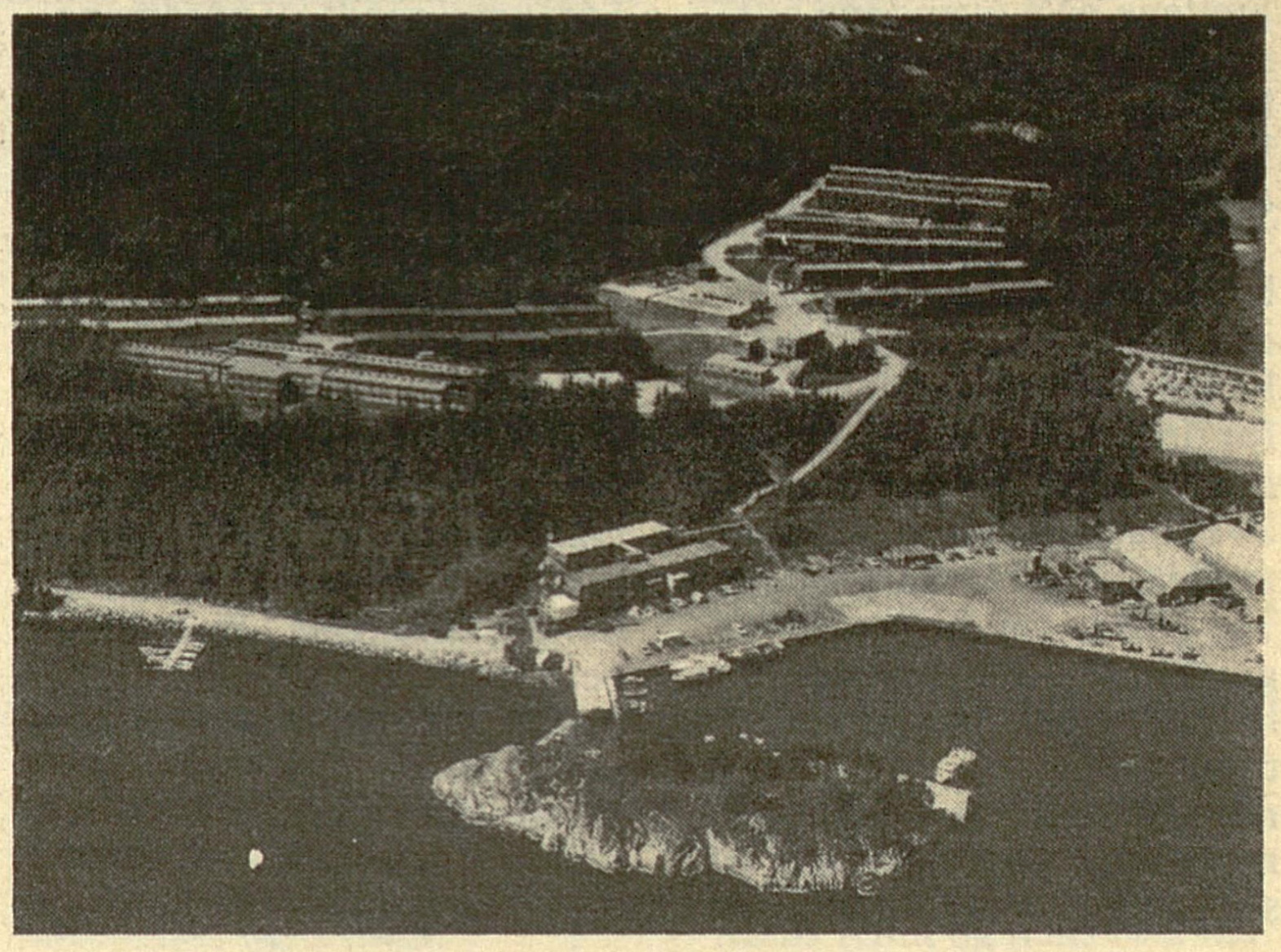

This was not the first time Vats was used for concrete platform construction

that required great depths. The first use came in the summer of 1976, during

deck outfitting for the Brent D platform. Statfjord B and C also stopped by

for completion work.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Om Brent D og Statfjord B og C i Vats, se Steen, Øyvind 1993. På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973-1993. Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, pp. 24 og 46. As a result, a sizeable barracks camp already stood at the Raudnes industrial area by the Vatsfjord when Gullfaks B and C arrived. In 1987, however, it had been nearly three years since the previous major influx of construction workers.

This time, the scale was bigger than ever, since two platforms were to be

based here at once (parts of the spring and summer of 1987). Stavanger

Aftenblad called it nothing less than “a historic and gigantic spectacle in

fjord, mountain, engineering and concrete that will hardly be seen again any

time soon. An enormous tourist attraction that is hard to reach. You’ll need

boat transport if visitors are to enjoy the concrete attractions in the

Yrkjefjord.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Førde, Thomas et al. 1987. Historisk sommer: Klondyke i Vats. In: Stavanger Aftenblad 27.03.1987, p. 13.

A separate base with capacity for 500 construction workers was

also established at Ramsvik on the south side of the Yrkjefjord. It was built

by Aker Contracting, which had been awarded extensive work on outfitting the

concrete cells of Gullfaks C.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid., p. 13.

All that remained was the final readiness for the formidable influx of around

2,000 people who would be working in the area. With that many people in such a

small place, it’s no wonder some asked: how on earth would this play out?

Read more: The Concrete Metropolis