Counting majorities at Gullfaks

The first part of this article examines how voting rules in Norwegian offshore licenses have evolved over time. The second part reviews changes in the ownership structure of the Gullfaks license and explains what has constituted a valid majority in cases where license partners have disagreed.

When companies are awarded a production license, they must form a joint venture (interessentskap) to carry out petroleum activities in the licensed area. Broadly speaking, the joint venture functions like a limited company. Revenues and expenses are shared in proportion to each partner’s equity share, which must always match their interest in the production license.

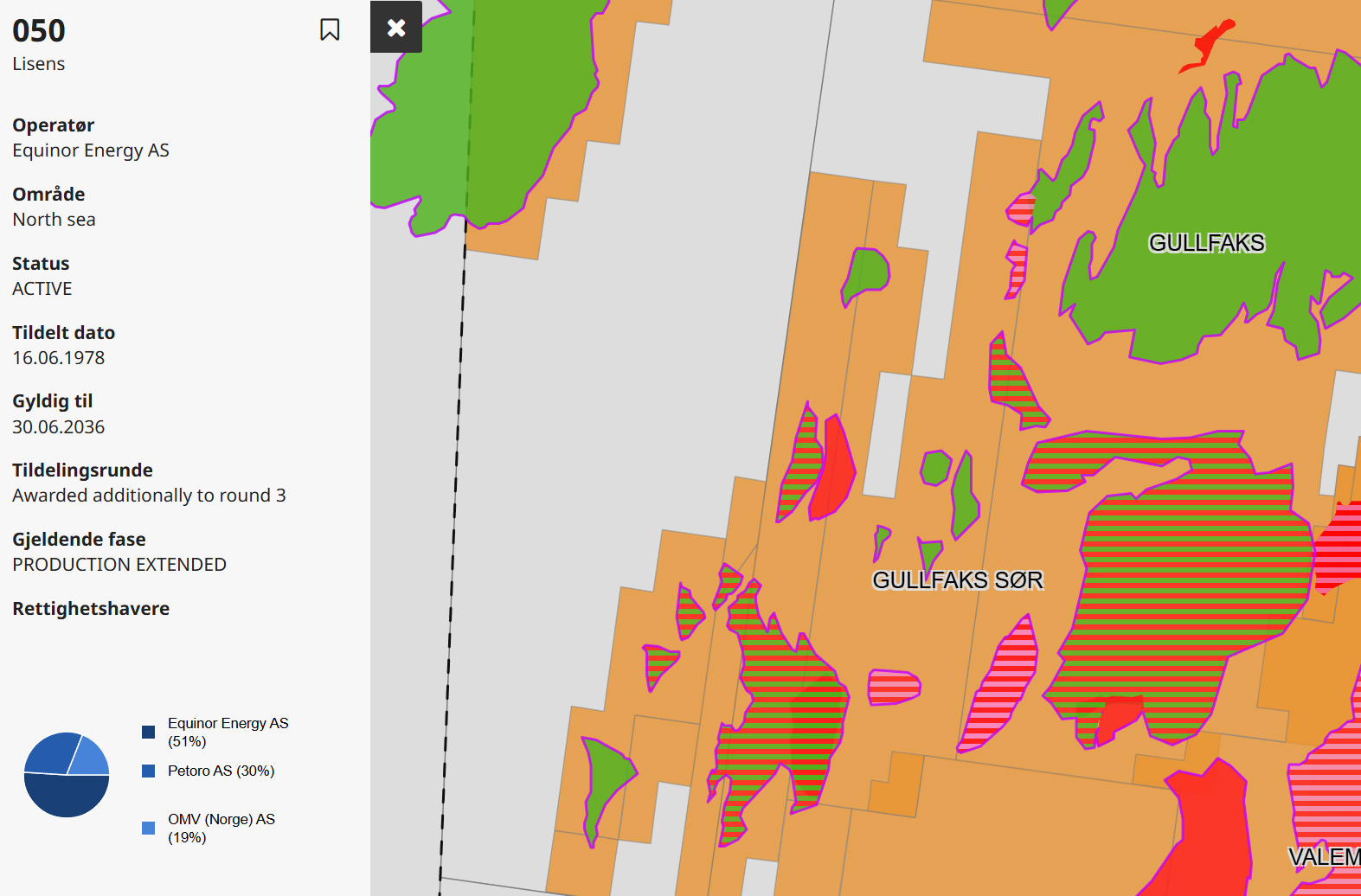

For Gullfaks, the ownership distribution in the license—and therefore in the joint venture—as of 2025 is: Equinor (51%), Petoro (30%), and OMV (19%).

Voting rules

When companies form a joint venture, they start from a standard agreement developed by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Among other things, this agreement outlines the voting rules—what it takes to form a majority and push a decision through. While the parties can in theory make adjustments that deviate from the standard model, this is rare.

According to the standard agreement, a decision must be supported by companies that collectively hold at least 50 percent of the equity in the license. In addition, there are restrictions on what such a majority can do. At least two companies must support the decision—even in cases where one company alone holds more than 50 percent. For example, between 2001 and 2007, ownership at Gullfaks was distributed among Statoil (61%), Petoro (30%), and Hydro (9%). In practice, this meant that Statoil needed the support of either Petoro or Hydro, despite holding a clear majority. The agreement also prohibits decisions that would unreasonably benefit one party at the expense of others. This provides a clear minority protection mechanism.

Two versions – with and without Petoro

As of 2025, there are two standard versions of the joint venture agreement: one for licenses where the state, through Petoro, is a participant, and one where the state is not directly involved. The main difference lies in the voting rules.

In licenses where Petoro is a partner, the standard agreement includes additional protections for the minority. It explicitly limits the state’s ability to impose its will—recognising that the state owns both Petoro and most of Equinor. Petoro and Equinor cannot form a majority on their own. Even if they together hold over 50 percent of the license, they must gain the support of at least one other company—unless they are the only two participants in the license.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Sokkeldirektoratet. (23.05.2024) Petroleumsloven og konsesjonssystemet. Hentet 9. oktober 2024 fra https://www.norskpetroleum.no/rammeverk/rammeverkkonsesjonssystemet-petroleumsloven/

Voting rules then and now

The 2025 version of the standard agreement is designed to prevent Equinor and Petoro from overruling the commercial companies in a license. But this type of minority protection was not always in place. In the 1970s and 1980s, Statoil held a more dominant position and had greater ability to push through its preferences in the event of disagreement.

Two years stand out as especially important in the development of voting practices: 1984 and 1994.

In 1984, the Norwegian Parliament separated the State’s Direct Financial Interest (SDFI) from Statoil’s portfolio. Statoil continued to manage the SDFI holdings on behalf of the state until 2001, when Petoro was established following the partial privatisation of Statoil. Although Statoil managed the SDFI interests, the shares formally belonged to the state—not to Statoil. As a result, the SDFI holdings did not automatically increase Statoil’s voting power.

However, Statoil could apply to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy for permission to count the SDFI shares as part of its voting weight.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thomassen, E. (2022). Middel og mål: Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget. (s. 242). If it presented a convincing case and needed a majority, it could be granted temporary voting rights for the state’s shares in order to reach the 50 percent threshold.

In 1994—ten years after the SDFI reform—additional restrictions were introduced as a result of the EEA Agreement, which Norway had signed two years earlier. The EU’s Licensing Directive (Directive 94/22/EC) required Norway to avoid giving unfair advantages to companies owned wholly or partially by the state. Licenses had to be awarded based on objective, pre-defined, and non-discriminatory criteria.

EU directives differ from regulations in that they define the goal but leave it up to each country to decide how it should be implemented. Norway complied with this directive by limiting the state’s ability—via Statoil, the SDFI, and later Petoro—to force decisions in joint ventures.

These changes were not retroactive. As a result, there is a clear divide between licenses awarded before and after 1994. Newer licenses give commercial companies greater ability to block decisions they disagree with, even when Equinor and Petoro hold a majority.

Gullfaks-majority

The remainder of this article looks at how the ownership structure in the Gullfaks license has changed over time, and what has counted as a valid majority in different periods. Gullfaks was licensed long before the EEA Agreement came into effect, and since the 1994 directive was not retroactive, the state has had more room to manoeuvre at Gullfaks than in newer licenses. This distinction matters, as Statoil and the state (via the SDFI or Petoro) have consistently held a clear majority at Gullfaks.

It is worth noting, however, that the dynamics within a petroleum license differ from those in a parliamentary setting. It is rare for one group of partners to push through a decision against the will of another. While possible, such votes are uncommon. The norm is to seek consensus and find solutions that respect minority views.

That said, there have been exceptions. Saga Petroleum disagreed with Statoil and Hydro on how to proceed with Gullfaks Phase II. In another case, Statoil and Hydro jointly applied in 1983 to build an oil pipeline from the field, despite differing views among the partners. Both cases were politically significant and were ultimately decided at the national level—not solely within the license. Even so, they show that the partners have not always been able to agree.

Finally, it’s important to note that Petoro is not like other oil companies. It has fewer employees, never serves as operator, and almost always votes in line with the operator.

Majorities in the Gullfaks license

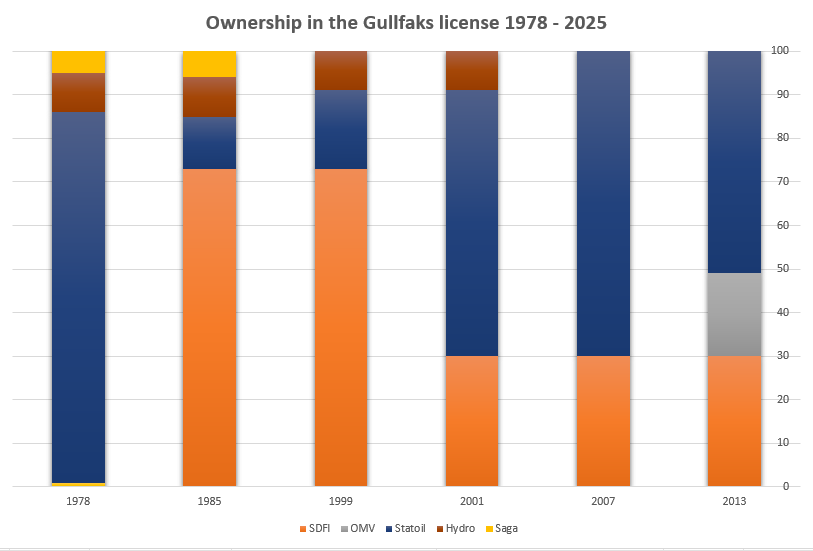

Compared to other fields on the Norwegian shelf, the ownership structure at Gullfaks has been relatively stable. Below is an overview of what has constituted a majority at various points in time.

1978–1985: Statoil (85%), Hydro (9%), Saga (6%)

In this period, Statoil could form a majority if it gained the support of either Hydro or Saga. Even though Statoil held more than 50 percent, decisions required the support of at least two companies. Hydro and Saga, with a combined share of only 15 percent, could not reach a majority on their own.

1985–1999: Statoil (12%), SDFI (73%), Hydro (9%), Saga (6%)

Following the 1985 Statoil reform, Statoil formally held only 12 percent of the license, while the state—via the SDFI—held 73 percent. In practice, little changed. Statoil could apply to use the SDFI shares to gain majority voting power, but still needed the support of either Hydro or Saga. The key difference was that after the reform, Statoil had to seek government approval to do so.

1999–2001: Statoil (18%), SDFI (73%), Hydro (9%)

When Saga’s shares were sold to Statoil in 1999, the company entered a phase where it needed Hydro’s cooperation to achieve a valid majority. Although Statoil had a large combined voting weight—especially when allowed to count the SDFI shares—it still needed a second partner to meet the requirement for two-company support. This gave Hydro considerable influence, despite holding just 9 percent.

2001–2007: Statoil (61%), Petoro (30%), Hydro (9%)

In 2001, the SDFI shares were formally transferred to the newly created state-owned company Petoro. At the same time, Statoil acquired enough shares in the Gullfaks license to hold a majority on its own (61%). But the requirement for support from at least two companies remained in place—meaning Statoil still needed backing from either Hydro or Petoro.

This period clearly illustrates the difference between pre- and post-1994 rules. Had the Gullfaks license been awarded under the post-1994 framework, a coalition of only Statoil and Petoro would not have been sufficient—Hydro would have had veto power.

2007–2013: Statoil (70%), Petoro (30%)

The merger of Statoil and Hydro’s oil and gas divisions ushered in a new phase of enforced consensus. Statoil held a clear majority, but still needed Petoro’s support to make decisions, due to the requirement for two-party agreement.

2013–present (2025): Equinor (51%), Petoro (30%), OMV (19%)

With OMV entering the license in 2013, the structure resembled the pre-merger setup. Equinor could form a majority either with OMV or with Petoro. However, OMV and Petoro could not form a majority without Equinor. Had the license been subject to the modern standard agreement, OMV would effectively have held veto power. But since the Gullfaks license was issued long before 1994, OMV has less influence than it otherwise might have.

The Gullfaks license stands out for its small number of partners, unusually stable ownership structure, and consistently large combined share held by the state and

Statoil/Equinor.