Diverless Production Wells on Gullfaks A – A Technological Breakthrough

In the early years of the oil age, diving was an essential part of offshore activities on the Norwegian shelf. Over time, however, it became clear that deep diving involved significant health risks. This led to increased focus on alternative solutions, and already in 1981 – in parallel with the launch of the Gullfaks A project – the issues surrounding deep diving were high on the agenda. The Norwegian Underwater Technology Centre (NUTEK) was established in Bergen as a national competence center for deep diving and subsea technology.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Hatlestad, H.L. (2021) 50 år med oljeproduksjon. Min historie. [Helge Hatlestad] og Innlegg på Gullfaks A sitt 33 års jubileum av Tor Nordgaard.

From Four to Three Platforms – The Need for Subsea Wells

The original development concept for the Gullfaks field was based on four platforms, but in the profitability report this was reduced to three. The condition for economic viability was then that subsea wells would have to be installed at a later stage. Statoil therefore planned to develop the field with seabed wells connected to Gullfaks A and C.

Mobil, the operator of the Statfjord field, had for several years been researching dry Christmas trees – i.e., wellheads that could be placed on the platform rather than on the seabed – as well as submarines that could dock with subsea installations. Despite considerable investments, the concept was never realized.

On Gullfaks A, however, the project management was early on convinced that the future lay in remotely operated Christmas trees mounted directly on the seabed, without the need for divers. This was a choice that would not only have consequences for Gullfaks but also lay the foundation for Norway’s leading position in subsea technology.

Statoil’s first subsea project involved engineering five standalone subsea wells to be tied back to Gullfaks A. The rationale for subsea wells was to recover reserves beyond the platform’s reach, accelerate production to improve the field’s economics, build competence and experience for future projects, and develop a diver-independent concept.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, K. Ø., Nergaard, A., Nergaard, Arnfinn, & Norsk oljemuseum. (2019). Subseahistorien: norsk undervannsproduksjon i 50 år. Norsk oljemuseum Wigestrand: 95.

While the original plan included five subsea production wells, in 1985 the concept was revised to three producers and one water injector, followed by one new producer in 1986. A fifth production well was tied in during 1988. The project thus comprised six identical standalone wells, each connected to Gullfaks A via separate flowlines.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, K. Ø., Nergaard, A., Nergaard, Arnfinn, & Norsk oljemuseum. (2019). Subseahistorien: norsk undervannsproduksjon i 50 år. Norsk oljemuseum Wigestrand: 94.

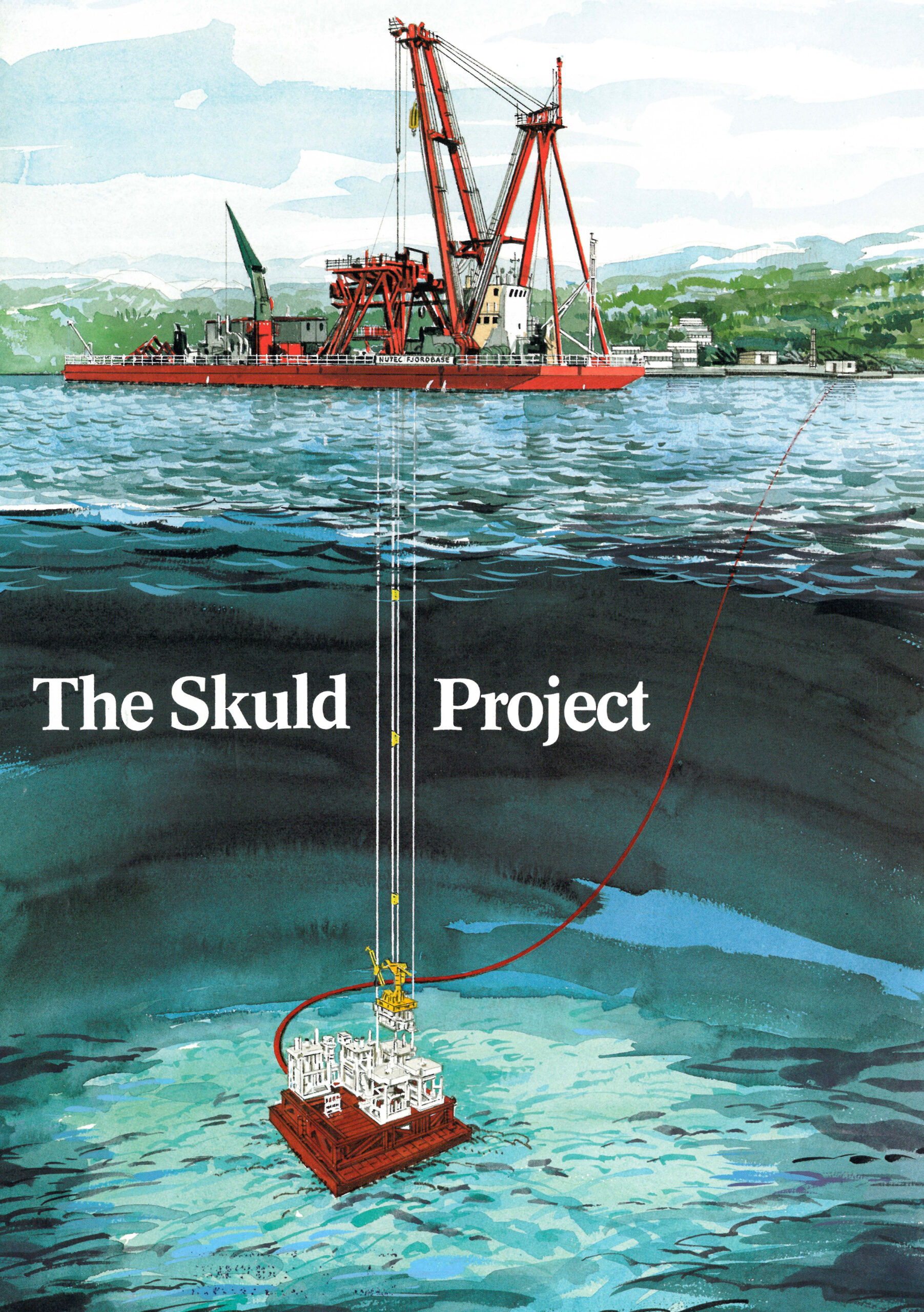

Experience from the SKULD Project

The project was carried out during the final phase of the diverless SKULD tests, in which Statoil was an active participant. Initiated by Elf in 1980, the SKULD project aimed to develop systems for remote control of subsea installations over distances greater than 20 kilometers.

The project included a test station pressurized and subjected to loads equivalent to those a production unit would experience in the North Sea. The SKULD module was intended solely as a research installation and was not to be used in commercial oil and gas production. The main goal was to develop an economical and simple method for exploiting fields in deep water, while ensuring the system was completely independent of divers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland. Trude. (2018.8. august). SKULD-prosjektet. Industriminne Frigg.no. SKULD-prosjektet – Frigg

The project represented groundbreaking technological work, with several key Norwegian players – including Statoil and Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk (KV) – participating actively. All tests were successfully completed, including simulation of a 20-year production period. The module concept, combined with diverless installation procedures, performed as planned.

The remote control system proved reliable, and the results from the simulation tests confirmed that the system was economically viable. SKULD technology attracted significant international attention, particularly for its functional remote control solutions and diverless installation methods.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Meland. Trude. (2018.8. august). SKULD-prosjektet. Industriminne Frigg.no. SKULD-prosjektet – Frigg

Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk – From Weapons to Subsea Technology

In 1984, Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk (KV) was awarded the strategically important contract for the subsea facilities on Gullfaks. KV had already developed dynamic positioning (DP) in 1977 with the Albatross system, which made it possible to keep vessels and rigs in position without anchors. The company had also established a partnership with Cameron Iron Works for the manufacture of wellheads, the first of which were produced in Kongsberg in 1974.

By 1980, fifteen subsea production wells had been installed on the Norwegian shelf – all requiring diver assistance. The demanding SKULD project had given KV valuable technological insight and competence.

The World’s First Diverless Subsea Production Wells

When the first wells came onstream on 22 December 1986 – almost six months ahead of the original schedule – Statoil and KV could celebrate Norway’s first diverless subsea production. Gullfaks A thus became a pioneer in using the first subsea wells that did not require diver intervention. This later became the standard for almost all subsea installations on the Norwegian shelf. The first three wells were ready for production in 1986, and start-up marked an important technological milestone.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Gjerde, K. Ø., Nergaard, A., Nergaard, Arnfinn, & Norsk oljemuseum. (2019). Subseahistorien: norsk undervannsproduksjon i 50 år. Norsk oljemuseum Wigestrand: 97.

Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk later described the Gullfaks project as its “final exam” as a supplier of subsea systems. The project laid the foundation for modern project management and quality control within the company. Statoil mobilized some of its top specialists in drilling, completion, production, and instrumentation, and at times had over 20 people stationed in Kongsberg to follow up on the project.