Building the Base Section

only one thing: this would be big and heavy. The groundwork was laid at

Hinnavågen.

The contract between Statoil [now Equinor] and Norwegian Contractors (NC) to

build the concrete substructure for Gullfaks C was, at the time of signing

(February 1986), the largest ever entered into by an industrial company in

Norway. It was valued at NOK 2.5 billion. To meet the project deadlines, NC had

begun work even before the formal signing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Risholm, Toril (25 January 1986). “Gullfaks C – the largest and most

expensive in the world. Norwegian Contractors signed a 2.5-billion-kroner

contract.” In: Stavanger Aftenblad, 25 January 1986, p. 6. See also Steen,

Øyvind (1993). “På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973–1993,” p. 47.

The fact that NC began work before the contract was formally signed had

happened earlier as well; see, for example, regarding Statfjord C:

Meland, Trude. “NC Starts Work on Statfjord C.” In: Industriminne

Statfjord

https://statfjord.industriminne.no/nb/2019/12/03/nc-i-gang-med-statfjord-c/

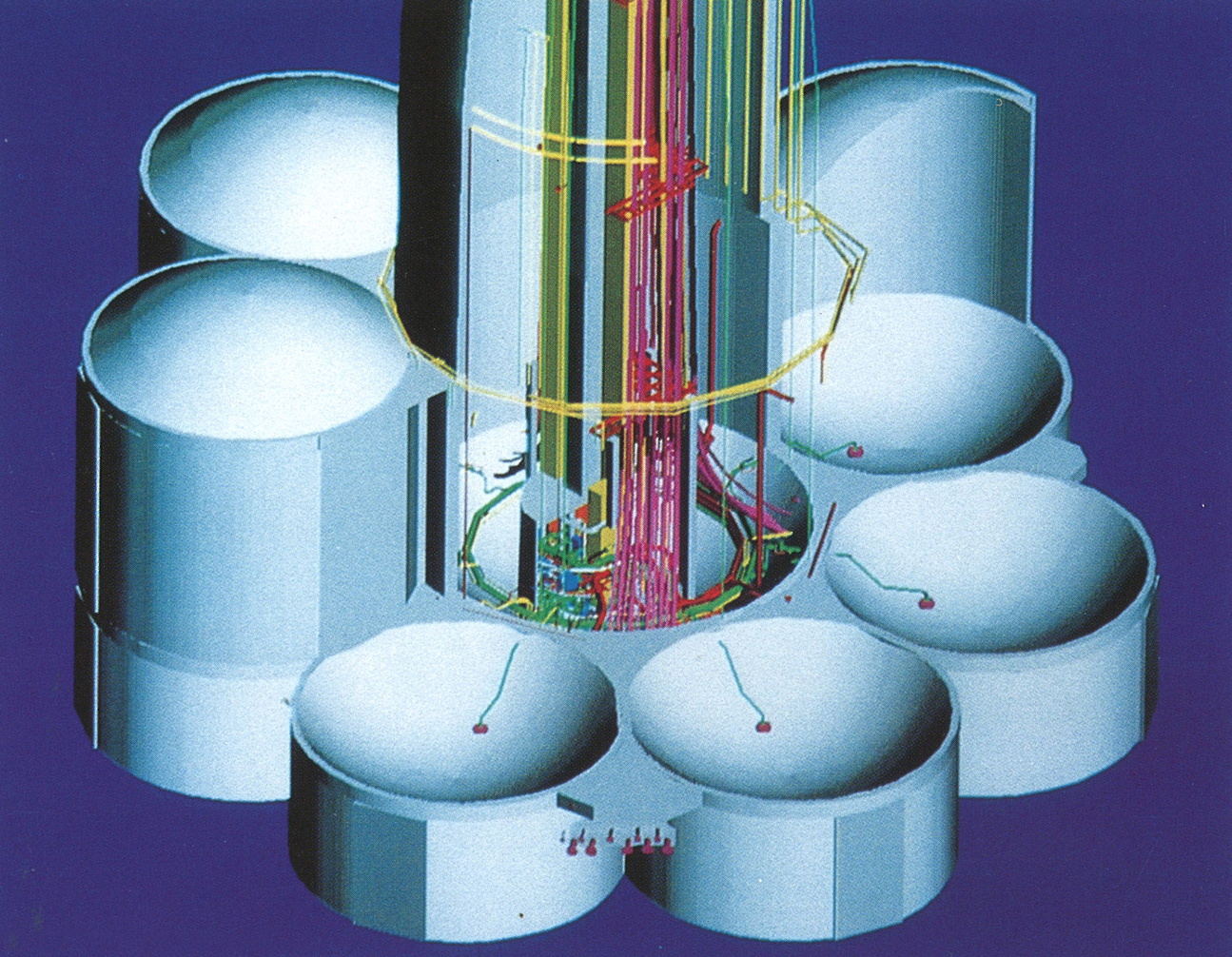

Construction started at Hinnavågen. The base section consisted of the bottoms

of the individual cells and their associated skirts.

By the summer of 1986, Stavanger Aftenblad could report on this “beehive in

Jåttåvågen” that “lies with its gaping cells, bearing witness to a level of

technology and effort that would relegate nature’s bees to extras,” where NC

“orchestrates the puzzle into place in a myriad of concrete, rebar, and steel.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hansen, Knut Egil (19 August 1986). “The Beehive at Jåttåvågen.”

In: Stavanger Aftenblad, 19 August 1986, p. 7

Condeep skirts in a new design / skirt piling

The combination of development in increasing water depths and challenging

seabed conditions (for example clay and soft sand) placed ever higher demands

on the design of the Condeep base sections.

For stability, most platforms of this type needed skirts—structures set into

the seabed to anchor and stabilize the rest of the platform, essentially a

foundation. Several earlier Condeeps had such skirts made of steel and/or

concrete.

In the 1980s, Olav Olsen, Norwegian Contractors, and the Norwegian

Geotechnical Institute (NGI) collaborated to develop and test cylindrical

concrete skirts as a direct continuation of the cells, and taller than those

used previously. This was termed skirt piling and was intended for great depths

and unfavorable seabed conditions.

Tests conducted in 1985 showed that, for this purpose, such cylinders could be

used as extensions of the storage cells. When, during the test, two cylinders

25 meters high (6.5 meters in diameter) were placed on the seabed, they

penetrated under their own weight and were further drawn in by negative

pressure (suction).

Although the Troll field was foremost in mind during the trials, the first

project where the concept was applied was the Gullfaks C platform. It was

fitted with skirt piles 27 meters long.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind (2002). “Den frie tanke – om kreativ frihet og en

ledende norsk ingeniør.” Lillestrøm: Byggenæringens forlag, p. 105.

The height of the skirts made it challenging to move the base section out of

the 14 m deep dry dock. To achieve sufficient buoyancy, air had to be pumped

into the underside of the structure. This had been done before but—as with

most aspects of this platform—the volume was larger than ever: 350,000 m³ of

air.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk oljerevy / Norwegian Oil Review. 1987, Vol. 13, No. 3, p. 26.

Platforms……. https://www.nb.no/items/9d80d3c7cce66b24c00748cb42e71745?page=35&searchText=%22Gullfaks%20C%22

In preparation for the construction project, significant work was carried out

to remove 50,000 cubic meters of seabed material to widen the passage from the

dock to deeper water in Gandsfjorden. This passage had to be at least 170

meters wide and 14 meters deep.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk oljerevy / Norwegian Oil Review. 1987, Vol. 13, No. 3, p. 36.

“Towards the end of the major orders for NC.”

https://www.nb.no/items/9d80d3c7cce66b24c00748cb42e71745?page=35&searchText=%22Gullfaks%20C%22

Once out in Gandsfjorden, the tow-out could begin toward the deep fjord

landscape at Vats, where the main slipforming and the shaft slipforming were to

take place.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Steen, Øyvind (1993). “På dypt vann. Norwegian Contractors 1973–1993.” Oslo: Norwegian Contractors, pp. 48–49.