At Risk of Being Neglected?

Initially, the ownership of Gullfaks was split between Statoil (85 percent), Hydro (9 percent), and Saga (6 percent). When the Willoch government introduced the State’s Direct Financial Interest (SDFI) in 1984, 73 percent of Statoil’s share in Gullfaks was transferred to the state.

Gullfaks became the field where the state — through the SDFI — held by far its largest direct ownership stake.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.meld. 21. (1992). Statens samlede engasjement i petroleumsvirksomheten i 1992 (S. 34). Statoil was left with a modest 12 percent share, while still retaining operator responsibility.

Arve Johnsen pointed out, including during a speech in Steinkjer in the autumn of 1984, that no operator had ever held such a small share in a field under development.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status: Internavis for Statoil-ansatte, (1984, nr. 17, s. 3). Statoil opposed the transfer of Gullfaks shares, arguing that a higher equity stake would lead to greater effort and stronger ownership of the operator role.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B. V. (2006). 34/10 Olje på norsk – en historie om dristighet. Statoil, s. 51. Whether that claim holds water is not entirely clear — but it’s worth examining.

Does ownership share matter?

If we look at the Gullfaks field in isolation, one could argue that the size of the operator’s ownership share has little or no practical significance. The license’s costs and revenues are distributed among partners according to their respective shares. An investment that yields a 10 percent return for an operator with 85 percent ownership would still yield the same return rate if the operator held only 12 percent.

Norway’s petroleum tax regime is largely built on this principle. As long as the state — whether through the tax system or SDFI ownership — assumes a proportional share of costs and revenues, it should not affect the companies’ behavior.

All fields are equal — but some are more equal than others

While the tax rate is uniform across fields, SDFI ownership is not. This creates the potential for conflicting interests, as companies hold varying ownership shares across different licenses.

This means companies may be incentivized to favor fields where they hold a larger stake, potentially at the expense of fields where their stake is smaller — particularly in situations involving overlapping infrastructure or shared resources. In short, an operator might boost its overall return by “shifting” value from fields in which it has small shares to those where it holds larger ones.

For example, a company might choose to allocate limited resources — such as personnel or technical equipment — to the field where it holds the largest share, even if using those resources elsewhere would generate more value for society. In that case, petroleum resources are not being managed in a socio-economically optimal way. These kinds of conflicts are most likely to affect the state (through the SDFI), which is not the operator and plays a more passive role in day-to-day operations.

So, while Statoil having just 12 percent of Gullfaks should not, in itself, have led to poorer management of the field, the fact that this was a lower share than in many of its other licenses may have given the company a reason to deprioritize Gullfaks — especially if doing so would benefit another license in which Statoil and its partners held larger stakes.

The Tampen area includes several oil and gas fields in close proximity that rely on much of the same infrastructure.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Askheim, S. (n.d.). Tampenområdet. Store norske leksikon. Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://snl.no/Tampenomr%C3%A5det The original SDFI portfolio gave the state widely varying ownership shares across these fields. While the state acquired 73 percent of Gullfaks, it had no direct stake in Statfjord — a field that the Labour Party had insisted Statoil should retain in the 1984 Statoil reform negotiations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thommasen, E. (2022). Middel og mål: Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget. (s. 243). Even today, the state has no direct ownership in Statfjord. Such uneven ownership distribution across overlapping fields created incentives to favor some fields and neglect others.

Just as attractive to send money to the state?

From 1984 until Statoil’s partial privatization in 2001, Statoil managed the SDFI portfolio. That meant Statoil was not only managing its own shares, but also acting as custodian of the state’s interests. For practical reasons, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy preferred that Statoil hold a stake in every block where the state had a direct interest.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Thommasen, E. (2022). Middel og mål: Statoil og Equinor 1972-2001. Universitetsforlaget. (s. 242).

Throughout that period, Statoil was obligated to manage both its own and the state’s interests in a way that maximized the combined return — meaning it was not supposed to prioritize its own shares over the SDFI’s when the two were in conflict.[REMOVE]Fotnote: St.meld. nr. 28. (1992). Statens samlede engasjement i petroleumsvirksomheten i 1991. (s. 37).

Intuitively, one might assume that Statoil had more incentive to prioritize revenues that went into its own accounts over those that went to the state, making such a rule necessary. But that may not be entirely accurate. At the time, Statoil had reason to hope that the SDFI shares would eventually be returned to the company. During the lead-up to the 2001 privatization, CEO Harald Norvik even proposed that all of the SDFI shares be transferred to Statoil — free of charge. If Statoil believed that the shares would one day come back to them, it would have had a clear interest in managing the state’s ownership as if it were its own.

There are two main reasons to believe that Statoil, between 1984 and 2001, actually managed the SDFI shares in line with its own: first, it was required to do so; and second, it hoped the shares might eventually return.

Kyrre Nese — who served for many years as platform manager on Statfjord and worked closely with Statoil’s leadership ahead of the partial privatization — explained that all decisions made during the SDFI period were guided by what would benefit the combined interests of Statoil and the state. According to Nese, this approach was consistently upheld and closely followed by CEO Harald Norvik, who may also have been motivated by the belief that the SDFI shares could eventually be transferred back to Statoil in the future.[REMOVE]Fotnote: From an email exchange between the Norwegian Petroleum Museum and Kyrre Nese.

That said, the broader point still stands: highly uneven SDFI ownership across licenses creates a structural risk of underinvestment in some fields — especially when other companies, not Statoil, act as operators. It’s no secret that other companies on the shelf had little incentive to care about maximizing the state’s SDFI cash flow in isolation.

Wide variations in ownership

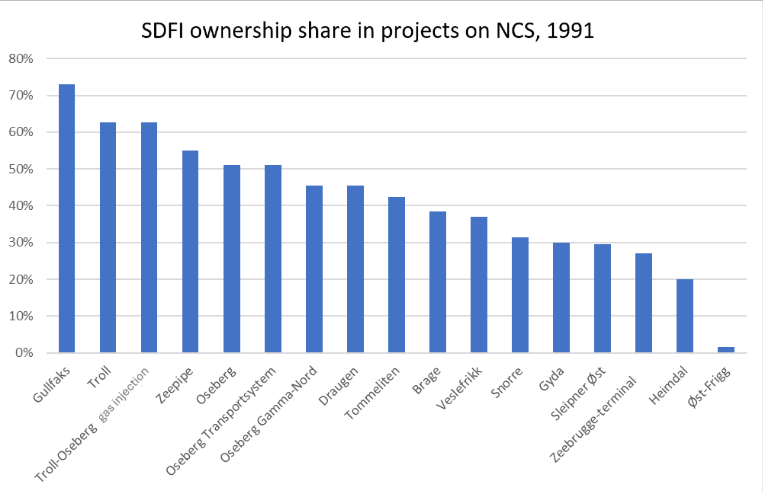

As shown in the table below, SDFI shares varied widely across projects in the years following its creation. In 1990, Gullfaks topped the list with 73 percent SDFI ownership, while Øst-Frigg was at the bottom with just 1.46 percent. Some licenses — such as Statfjord — had no SDFI share at all.

In 1991, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy recommended aiming for a more balanced SDFI portfolio. The goal was to reduce the likelihood that companies — particularly operators — would have large discrepancies in ownership shares across fields. In theory, this would lower the risk of companies favoring fields in which they held large shares.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stortinget. (1992). St.meld. 21: Statens samlede engasjement i petroleumsvirksomheten i 1992. (s. 36). If we focus only on licenses where Petoro is now a partner, we can say that the SDFI portfolio in 2022 was more evenly distributed than it was in its early years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The standard deviation of SDFI’s percentage ownership across licenses was 17.09 percent in 1991. By 2022, it had decreased to 9.74 percent. The calculation was carried out by the author.

Larger — and more balanced

The SDFI portfolio, now managed by Petoro, has likely become both more balanced and larger over time. In 1991, economics professors Viktor Normann and Øystein Nordeng estimated its net present value at NOK 350 billion (equivalent to NOK 694 billion in 2022).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Behandlingen av St.meld. nr 28. Statens samlede engasjement i petroleumsvirksomheten i 1991, s. 2731 https://www.stortinget.no/nn/Saker-og-publikasjonar/Stortingsforhandlingar/Lesevisning/?p=1990-91&paid=7&wid=a&psid=DIVL14&pgid=b_1261 In 2022, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries — with external assistance — valued the portfolio at NOK 1,584 billion. [REMOVE]Fotnote: Petoro. (2022). Årsrapport 2022 (s. 27). Petoro. retrieved from https://www.petoro.no/%C3%85rsrapport-sider/2022/pdf/PetoroAarsrapport2022.pdf

But rebalancing the portfolio through trades is easier said than done. Since Petoro was established, there have been few such transactions — partly because it’s difficult to ensure the pricing is fair. The largest such deal in Norwegian history — the state’s divestment in multiple licenses ahead of Statoil’s partial privatization in 2001 — was clearly a loss for the country. That experience likely left a lasting impression, limiting the frequency and manner in which Petoro trades license shares today.