A small gadget: big payoff

Today, permanently installed downhole reservoir and production monitoring systems are standard when wells are completed[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Komplettering,” Store norske leksikon (SNL), https://snl.no/komplettering, accessed May 7, 2024; “Completion (oil and gas wells),”Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Completion_(oil_and_gas_wells), accessed December 9, 2025. – that is, when a well is prepared for production after drilling and the casing is set. Until the late 1980s, such measurements were typically only done during well testing.

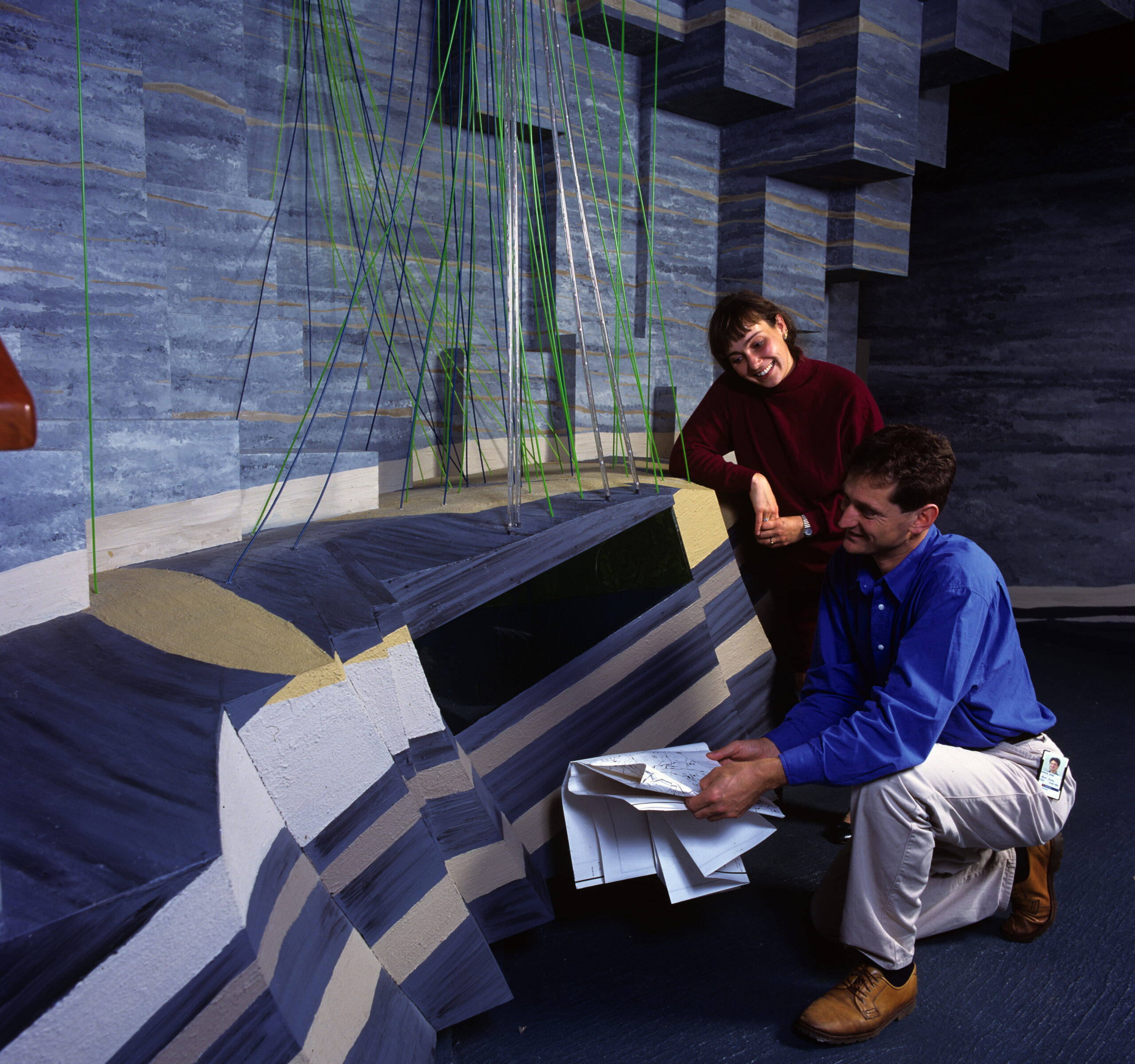

Hydraulic control lines made continuous measurements possible. The breakthrough was first put to work on the Gullfaks field.

The idea

During well testing, pressure and temperature measurements were commonly run to extract as much information as possible from the subsurface. The logging cable used to collect the data was protected by braided wire (wireline armor). That setup would survive a couple of days of well testing, but it wouldn’t protect the equipment permanently.

In 1984, Henning Hansen—then employed by Baker Hughes—was on a floating rig conducting well tests on Gullfaks.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The text is largely based on an interview with Henning Hansen, conducted by Björn Lindberg and Julia Stangeland, January 15, 2024. Henning Hansen sadly passed away in the autumn of 2025. Hansen worked on drilling-related tasks: well surveillance, completion equipment, and wireline operations.

Hansen asked the onboard reservoir engineer, Trond Unneland from Statoil, whether permanent measurements would be useful from a reservoir engineering perspective.

The answer was clear: permanent pressure and temperature data could deliver richer reservoir insight, enabling optimal field production.

As soon as Hansen got onshore, he sent a telex to Baker Hughes in Houston explaining the idea he and Unneland had discussed. He wanted to develop it. When Baker Hughes replied there was no business case and declined to pursue it, Hansen resigned and started his own company.

Together with Helge Skorve—also formerly at Baker Hughes—he founded Lasalle Pressure Data. About a year after the idea, they had built a gauge not protected by braided wire but by a hydraulic control line. They also made other minor tweaks. The new pressure and temperature gauge was designed to remain permanently in the well—if not forever, at least longer than three months, which they had calculated as the threshold for a positive payoff.

A calculated risk

To prove whether- and how well- the equipment would work, they needed someone willing to test it. Trond Unneland was ready to take that risk. As Hansen puts it, he was bold enough to try.

-He did a fantastic job, Hansen says, recalling how Unneland persuaded Statoil’s management that it was worth spending four extra hours per well to install the pressure and temperature gauge. Four hours of rig time is expensive, but the upside – if it worked – would far exceed the cost.

From 1985 to 1986, the new gauges were installed—on a test basis—in each of the five production wells drilled from Gullfaks A (not on seabed wells; those came later).

The gauges worked well, and the data volume was extremely useful. Unneland wrote an SPE paper (Society of Petroleum Engineers)—a peer- reviewed article—about the gauge and its impact. Within five or six years, such measurements had become standard in well completions.

What, exactly, did these gadgets do?

Permanent downhole reservoir- and production monitoring systems

In simple terms, a downhole pressure and temperature gauge consists of one or more sensors mounted on the production tubing deep in the well. The sensor connects to an electric cable that runs up to the Christmas tree (wellhead). The electric signal is routed through a pressure-tight barrier to a cable tied into a Data Acquisition System (DAS). In the past, this information was interpreted largely by hand; today, most interpretation is performed by computer.

The data give reservoir engineers direct insight into subsurface conditions and how each well produces oil and gas. With this equipment, reservoir engineers can optimize production.

Fun fact

Hansen and his colleagues needed a computer with 10 MB of memory to handle the large flow of data from the reservoir. The machine cost NOK 70,000. Because the purchase seemed extravagant – did they really need that much memory? – it had to be cleared by Statoil’s management. After some debate, they approved it.

A machine that “large” required an export license from the U.S. military. For approval, Hansen had to bring a letter from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) confirming that Norway was not the Soviet Union but, in fact, a NATO member—just like the USA.

When the machine filled up after a year, it was much easier to get the next one.

Note: By comparison, the computer used to write this text has 476 gigabytes of memory—one gigabyte equals 1000 megabytes.

A key premise for understanding the gauge is that a well always has pressure, and that pressure typically declines as the reservoir depletes. You can compare it to a bottle of soda. If you shake a full bottle and open it, it sprays; if there’s only a little left, less comes out.

The CO₂ in the soda bottle is analogous to the reservoir gas, while the oil is like the soda. If you crack the bottle, some gas comes out; if you only crack it a little, only a little gas escapes.

When you drill a well, the gas—being lighter than oil—rises, and gas takes up a lot of space—more than oil. Ideally, you want it to come up mixed with the oil. In the early days of Norway’s oil industry, operators were primarily targeting oil—that’s where the value was. It was therefore better to keep as much gas as possible down in the reservoir to help maintain pressure and push more oil out.

To maximize a well’s output, it can be tempting to open up fully—to take the cap off the “bottle,” i.e., the reservoir—and drain it fast. What then happens is that the gas breaks through first, occupies large volume, and actually slows the reservoir’s depletion performance.

Before gauges could stay permanently downhole, the well team would rely on feel for when gas might break through first and then set a safety margin 10–15 percent below that pressure. With a pressure and temperature gauge, they could measure this precisely. They could then control production more exactly, hitting the sweet spot that delivered as much oil as possible without risking a gas breakthrough ahead of oil.

The measurement system can also be tied to injection wells—wells where water is pumped down into the reservoir. Water injection helps raise reservoir pressure so more oil can be produced. By adding the measurement system to injection wells, it becomes easier to see whether injection is hitting the right zone.

Hansen believes the combined effect of using the pressure and temperature gauge raised daily production by around 10 percent and improved overall sweep—some 10–12 percent more of the reservoir was drained.

He has no doubt the equipment also helped extend the life of the Gullfaks field.

Standard production package

“We’re installing a production package. That means we need a sensor.” Today, there’s no longer any debate about whether to spend extra time installing a downhole pressure and temperature gauge, Hansen says. Within five to six years of proving the concept, it became standard. It is now so standardized that it’s part of the curriculum for well engineering students.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Standard utstyr i øvre komplettering,” Nasjonal digital læringsarena (NDLA), https://ndla.no/nb/subject:1:6951e039-c23e-483f-94bf-2194a1fb197d/topic:7aac6afb-7517-4bf0-8cbe-aade658012be/resource:1:181784, accessed August 15, 2024.

Hansen notes that Norwegian subsea technology gets a lot of media attention in Norway, but the recognition Norwegians deserve in well technology—in the small “gadgets” and “bits” tied to drilling—has been underreported.

Hansen estimates that 3,000–5,000 people now work with this equipment at companies like Baker Hughes (which eventually recognized its value), Halliburton, Roxar, and GEO PSI. The equipment is used worldwide, with a clear Norwegian fingerprint. The cable still carries a plastic jacket measuring 11 times 11 – even in countries that don’t use the metric system.

Many wells have since taken the next step to so-called intelligent completions—meaning they have pressure and temperature gauges and remotely operated valves. Fiber-optic cables have also become important.

When Statoil took the chance in the mid-1980s on permanently installed downhole pressure and temperature gauges, the Lasalle team hoped the gauges would last at least three months. The first one lasted eight to nine years, Hansen recalls. The well was then recompleted with a new gauge – for the simple reason that the little gadget paid off.