1:33 ⅓

Large, precise structures require drawings. Which rooms should have water? Where will the power cables run? Where must the toilets be placed to connect into the sewage system? How should the house sit on the plot, and where should windows go to get the best natural light? Should the staircase be there? How will the flow work when groceries are carried from the front door to the kitchen?

If we assume a house with a 100‑square‑meter footprint, the complexity of that single level alone can be multiplied by 60. The biggest platforms have a footprint approaching 6,000 square meters.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk oljerevy = Norwegian Oil Review, 1989, vol. 15, no. 3, 11.

Complexity rises further with each added deck, with more pipes, valves and equipment – and with every additional party involved in construction.

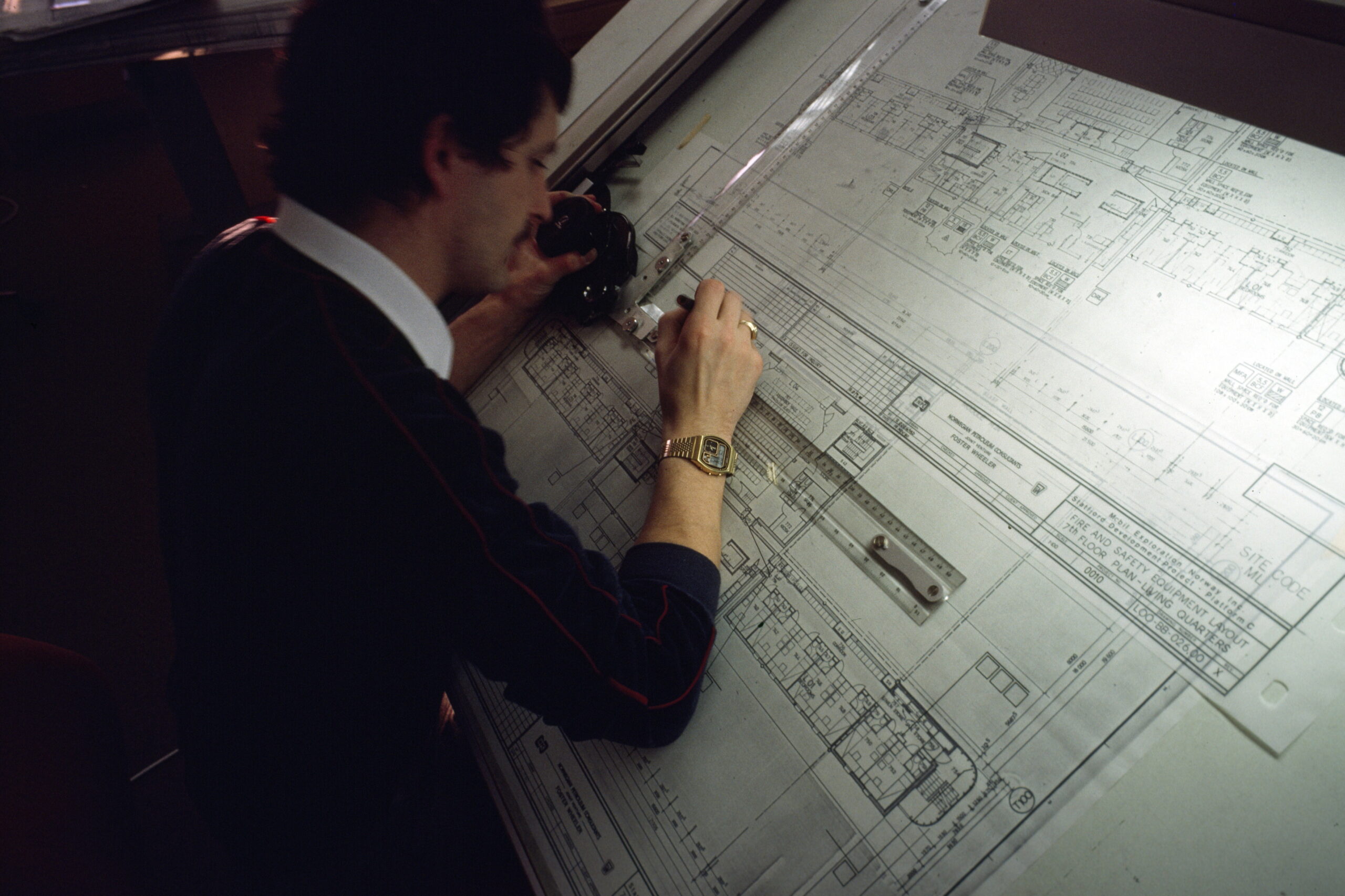

A house project is often small enough that one person can keep oversight and spot a mistake on a drawing. That is not possible when building platforms. The drawings must be trustworthy – one hundred percent correct. Today, engineers use advanced software to check the complex drawings.

In the 1970s and 1980s, that was not an option. Back then, large‑scale engineering models were built to verify that the drawings matched reality.

The engineering model

The three Gullfaks platforms, like others, were built in sections – modules. The steel topsides deck frame formed the foundation for all modules to come, from the living‑quarters module to the flare boom. Gullfaks modules were fabricated from Tønsberg in the southeast to Sandnessjøen far in the north. Some modules were also built abroad.

Some yards delivered multiple modules and made use of subcontractors. Work, naturally, was carried out to drawings.

The same applied to the substructure: the base, the cells, and the legs on which the platform deck would rest.

Errors in drawings could be expensive to fix. To uncover such problems, teams built complex models at large scale. The standard scale was 1:33⅓.

Kjell Eines, a model builder on one of the Oseberg platforms, told the TV show “Norge Rundt” in 1988 that one error they caught was a freshwater pipe running straight into a steel wall. The drawing had to be redone. Eines estimated that fixing it on the actual platform would have cost between NOK 100,000 and 150,000[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK, Norge Rundt, “Bergen: Modellbygging i oljeindustrien,” aired July 29, 1988, https://tv.nrk.no/serie/norge-rundt/sesong/1988/episode/FREP44009988#t=13m59s, accessed March 19, 2025. – roughly NOK 300,000 in 2024 terms.

The construction of Statfjord A shows how badly things could go. Due to lack of experience and time pressure, drawings were produced almost in parallel with platform construction. At times a drawing was revised after the work had been completed, forcing demolition and a restart. It was inefficient, uneconomical, and demotivating for the people doing the building.

Of particular importance was the piping system. Other checks focused on material flow. Would it be possible to move containers to where their contents were needed? Could large equipment be brought out and in – for repairs or replacement? HSE was another focus area, for example fire doors and fire zones.

Models also served as strong visual aids that made it easier to envisage the platform and solve problems. Because the model was modular, just like the real platform, the modules could be used as a dry run for installing the actual modules. Models could also be sent out as a visual aid to the shops fabricating the various modules.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Modell,” engineering model of Statfjord B, DigitalMuseum / Norsk Oljemuseum, https://digitaltmuseum.org/011025060597/modell, accessed April 7, 2025.

The model builders

Clive Lawford and Jan B. Andersen both worked as model builders in the 1980s. They say the work demanded precision, and it was not uncommon for errors in the drawings to force rework. Finding such errors could be satisfying, knowing they would not carry over to the real platform, but the errors could just as easily be a source of frustration.[REMOVE]Fotnote: All information from Clive Lawford and Jan B. Andersen is based on an interview conducted with them in the museum’s collections storage, February 5, 2025. The interview was carried out by Kirsten T. Hetland and Julia Stangeland.

Lawford recalls wrestling with a problem for a long time and concluding that the drawing itself must be wrong, rather than that he had misunderstood it. When he raised it with an engineer, he was told several new drawings had been produced after the one he had been given.

Andersen confirms that not having the most up‑to‑date drawing was a commonproblem. Another was that the drafter would not always admit a mistake.

Many of the piping specialists were English, who tried to be heroes night and day. Andersen remembers one occasion where he found about eleven errors in the pipe routing. The drafter would not admit the mistake until Andersen threatened to take the matter up with his supervisor. When your eyes started to cross, it was easy for the pipes to do the same.

Model builders were few, specialized, and worked in small model‑building firms often located along Norway’s west coast, near the fabrication yards. Several model builders moved between the few companies that existed, and when they worked on models over longer periods they were often seconded to the company.

It was often in small rooms without windows, frequently in the basement, recall Andersen and Lawford. There they assembled enormous plastic puzzles, often exposed to chemicals that really should have triggered better ventilation.

Like the real platforms, the models were made up of multiple modules. Given the size, models were seldom assembled at their full height. This was true not least for the platform legs, which at full model height could be as much as eight meters tall. Ceiling height was not the only constraint, building models at such heights would not have been very practical either.

Engineering models were typically built by up to three people over a periodof about two years – always a little ahead of the actual platform.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK, Norge Rundt, “Bergen: Modellbygging i oljeindustrien.”

When the engineering model was finished, it had in some sense completed its mission: the drawings had been checked. Could the model still be used once the platform itself was also finished?

Reuse

Building the Oseberg model in 1988 cost around NOK 10 million at the time, which corresponds to about NOK 24 million in 2024.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK, Norge Rundt, “Bergen: Modellbygging i oljeindustrien.”

Compared with the planning and construction cost of a platform, that is small change. And given that the very act of taking the time and money to build an engineering model could deliver major savings by revealing errors, it was also money well spent.

At the same time, it is no surprise that oil companies looked for ways to reuse this investment.

Several models were used to train future offshore workers. They could study escape routes and get familiar with the platform before their first trip offshore. Platform models may also have had value in emergency preparedness work offshore.

Platform construction was visible in many places along the Norwegian coast, and many people had seen platforms on television and in print. Even so, the platform as a phenomenon was still quite new. That was likely one reason why not only engineering models were made, but also smaller models for general public outreach.

Among these was a platform model of the Gullfaks A platform that Statoil displayed at the oil exhibition ONS (Offshore Northern Seas) in Stavanger in 1984. It was later placed at Statoil’s office at Sandsli in Bergen, before being moved to the company’s head office at Forus in Stavanger.

Today you can find thousands of platform photos on the internet. Computers have also replaced the need for engineering models. Other models are often imported, which means there are few practicing model builders in Norway today.

For many, model building was a hobby that became a profession. Today it has again been reduced to a hobby – and some maintenance on models held by museums.

Gullfaks models at the Norwegian Petroleum Museum

We do not know for certain how many engineering and other models existed for the three Gullfaks platforms. Perhaps there was one engineering model for each of them? What is certain is that more existed than have been preserved.

Some examples are in the Norwegian Petroleum Museum’s collection: the previously mentioned model of Gullfaks A, an engineering model of the drilling derrick on Gullfaks C, and more or less complete engineering and other models of the equipment shaft, seawater shaft and drilling shaft for Gullfaks C. An engineering model of Gullfaks B is held by The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology and is additionally well documented in photographs.

The Gullfaks A model is on display in the museum, while the other models are kept in the museum’s storage facility.

In addition, a model of Gullfaks C was made for the opening of the museum. This one illustrates how the concrete substructure of Condeep platforms (platforms with a substructure of reinforced concrete) was built.

The museum also holds other models directly or indirectly linked to the history of the Gullfaks field, such as a model of the field itself, a model of one of the many shuttle tankers that carried oil from the Gullfaks field, and a model of the loading buoy system used to pump oil from the platforms to ships.

Models were built to save money, for training, and to show what a platform actually looks like. Few people get the chance to visit a platform, but they can study them through models – by visiting a museum, via the photos in this article, or by visiting the Digitalt Museum website.